This is the second part of a two-part series about a class project on online filter bubbles. In this post, where we focus on the results. You can read more about our pedagogical approach and how we carried out the project here.

By Janet Xu and Matthew J. Salganik

This past spring, we taught an undergraduate class on social networks at Princeton University which involved a multi-week, student-led collective class project about algorithmic filter bubbles on Facebook. We wanted to expose students to the process of doing real research, and filter bubbles seemed like an attractive topic because they are interesting, important, and tricky to study. The project—which we called Breaking Your Bubble—had three steps: measuring your bubble, breaking your bubble, and studying the effects. In short, all 130 undergraduates in the class measured their Facebook News Feed for four weeks—recording the slant (liberal, neutral, or conservative) of the political posts that they saw. Then, starting in the second week of the project, students implemented procedures they had developed in order to change their News Feeds, with the goal of achieving a “balanced diet” that matched the baseline distribution of what is being shared on Facebook. Students also came up with public opinion questions for a big class survey, which they took at both the beginning and the end of the project. You can read more about what exactly we did, how it worked, and what we’d do differently next time here.

Though our primary goal was to teach students about doing research, we also learned some surprising things about the Facebook News Feed from the aggregated student results.

News Feed Composition

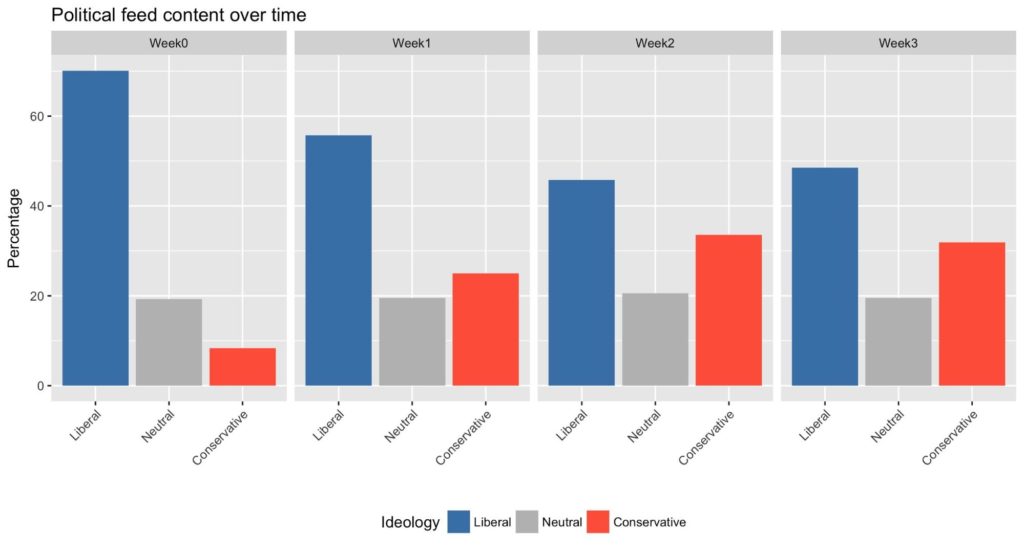

So, were students able to break their bubble? Initially, we expected that because the News Feed algorithm is complicated, it might be hard for students to break out of their bubbles. But we were wrong. The class was able to move to a more balanced diet pretty quickly. Here’s the change in their News Feeds in the aggregate.

By weeks 2 and 3 the results are very similar to the target distribution, which was the type of content being shared on Facebook overall as reported in Bakshy et al (2015).

Even though students in each of the 12 precepts (that’s what we call discussion sections) came up with their own strategies for breaking their bubbles, almost all of the 12 strategies worked well. To be fair, some of those strategies shared the same tactics (e.g. like new Pages that are not aligned with your political beliefs). But we were still surprised that pretty much all of the strategies worked for achieving a balanced feed.

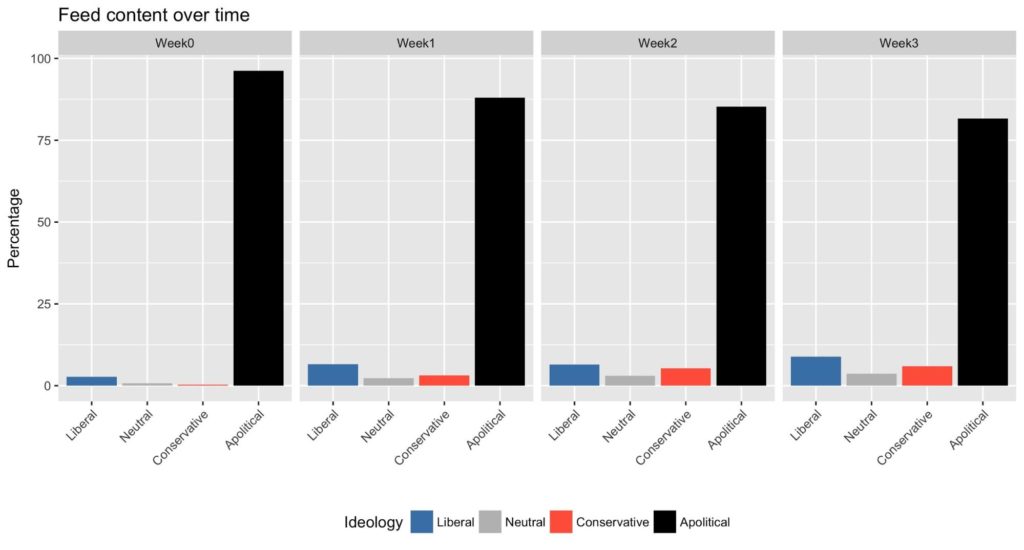

The second major unexpected finding is that our students’ News Feeds just aren’t that political. Plots like the one above are a bit misleading because they show the ideological distribution of political content. However, most content in their News Feeds is not political. Here’s a different way of looking at the same data:

Political news makes up less than 20% of News Feed posts, even after students had deliberately sought out more political content by following new media outlets. This important point is missed by services like The Wall Street Journal’s Blue Feed, Red Feed, which just focus on political stories (a point that already been made elsewhere). On students’ real News Feeds, each political post is surrounded by memes, personal posts, apolitical ads, and more memes. Some students reported scrolling through hundreds of posts before coming across five political stories.

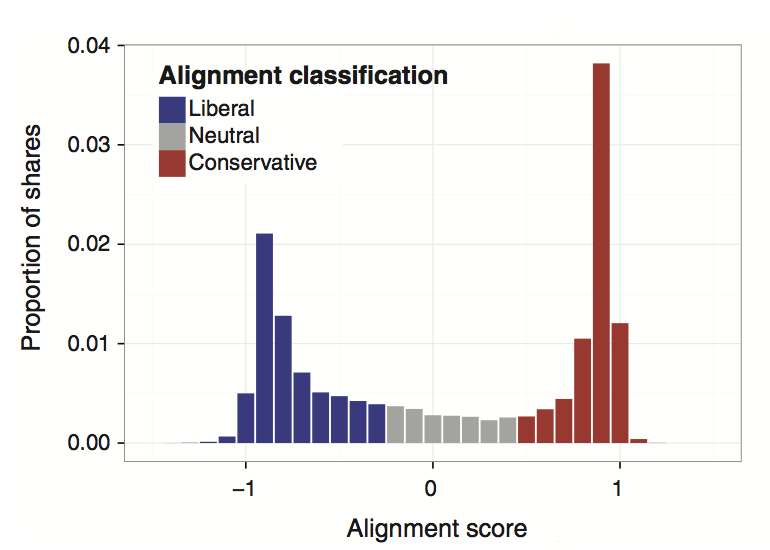

Moreover, we learned that students didn’t break their bubbles by a one-to-one replacement of belief-consistent news with cross-cutting news. In trying to consume more cross-cutting news, they also ended up consuming more belief-consistent news. For example, a liberal student saw a higher proportion of conservative stories among the political news in their News Feed after the activity, but they also saw more liberal stories among their overall News Feed content than they did before. Or, to extend our “balanced diet” metaphor further, we can think of cross-cutting information as vegetables and information that is consistent with prior beliefs as meat. Before the activity, people ate a lot more meat than they did vegetables. But in the process of achieving balanced diets, people had to eat a lot more food in general. The new food they ate was mostly vegetables, but they also ate a little more meat. In the end, their diets were more balanced, but they still ended up eating more meat than they did at the beginning.

Attitudes

Even though students were able to change the content of their feeds, our comparison of the pre- and post-bubble breaking survey didn’t reveal much change in attitudes. However, in addition to this rather crude survey-based measure, we also asked students to reflect on the experience. These reflections revealed some more subtle impacts that were missed in the survey:

Greater exposure to cross-cutting content increased awareness and perspective-taking: Many students reported that even though their personal stance on issues like gun rights, healthcare policies, foreign policy, and abortion didn’t change, they now have better understanding of why people on the “other side” have opposing views.

This inspired some students to be more informed and politically engaged: This statement from a student exemplified this theme: “Now that I have been liking these political pages online and reading more about what is happening in terms of US politics, I am beginning to understand and appreciate more about how tough these decisions are. Just yesterday, I saw online that Trump’s list of new tax cuts were coming out and prior to this experiment, I would never have known this or much less read it, but I clicked on the link and read about how he intends to cut taxes on business and individuals. I even read about how there is much debate as whether he is doing this under his own agenda because of how much the tax cut will save his own business revenue. Therefore, I am not sure if my exact attitudes are changing in terms of my political views, but I am sure that I am becoming more aware of what’s happening today.” Analogously, other students reported that they now care about a wider range of issues.

But there was also a backfire effect: Many students noted that exposure to opposing views actually caused them to embrace their prior convictions more—something akin to the backfire effect. Given that some students also saw a slight increase in news that were consistent with their prior beliefs, we might consider that this increased conviction is merely due to increased reinforcement. But almost all students who talked about this couched it in their experiences of reading the opposing views. For example, one student wrote, “the breaking of the bubble may have instead reinforced my views because of some of the poor writing and argumentation done by the opposing ideology.” Another student echoed, “even understanding the other side did not push me to agree with them. It actually strengthened my views on certain issues.” There were even a few cases where the cross-cutting exposure seemed to galvanize polarization; one student wrote that “if anything, I have become more convicted in my original views and more willing to voice them.”

And perceptions of other Americans did change: Filter bubbles don’t just encourage people to ignore opposing views; they also create the illusion that the opposing viewpoint is the minority. The activity seemed to have had greater effects for shattering the latter illusion. One student wrote, “The only belief of mine that changed was that there were more people that supported Trump than I had realized. I had read and watched videos praising Trump, which is something I hadn’t experienced before. Even though I disagreed with them and wasn’t swayed by their reasoning, it made me realize that these were huge media companies that must be running on a lot of support across the country that I wasn’t aware of.” Another student summarized this theme succinctly: “Breaking the bubble was more effective in changing my perception of the general distribution of views in the wider population than it was in changing my personal opinion on political issues.”

Conclusion

We set out to teach 130 undergraduate students about evaluating and doing real, modern research. In addition to learning about the realities of social science research, we all found out some things we didn’t quite expect about the Facebook News Feed, such as how students are able to break out of their bubbles if they make a consistent and concerted effort. We also got some nuanced insight into how students react to cross-cutting content when they’re exposed to it—in other words, what actually happens when filter bubbles are broken. Because of the methodology we used—described in a prior post—these results should be interpreted with caution, but we hope that they provide a starting point for future teaching and research.

Notes:

- Some of my (Matt’s) research has been funded by Facebook. This is on my CV, but we also explicitly disclosed this to the students, and we had a discussion about industry-funded research and conflicts of interest. I also pointed them to this article in the Intercept.

- Thanks to the other teaching staff for helping us shape this activity: Romain Ferrali, Sarah Reibstein, Ryan Parsons, Ramina Sotoudeh, Herrissa Lamothe, and Sam Clovis.