The FCC recently released the Open Internet Order, which has much to say about “net neutrality” whether (and in what circumstances) an Internet service provider is permitted to prioritize traffic. I’ll leave more detailed thoughts on the order itself to future posts; in this post, I would like to clarify what seems to be a fairly widespread misconception about the sources of Internet congestion, and why “net neutrality” has very little to do with the performance problems between Netflix and consumer ISPs such as Comcast.

Much of the popular media has led consumers to believe that the reason that certain Internet traffic—specifically, Netflix video streams—were experiencing poor performance because Internet service providers are explicitly slowing down Internet traffic. John Oliver accuses Comcast of intentionally slowing down Netflix traffic (an Oatmeal cartoon reiterates this claim). These caricatures are false, and they demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of how Internet connectivity works, what led to the congestion in the first place, and the economics of how the problems were ultimately resolved.

In fact, while there are certainly many valid arguments to support an open Internet, “faster Netflix” turns out to be a relatively unrelated concern. Contrary to what many have been led to believe, there is currently no evidence to suggest that Comcast made an explicit decision to slow down streaming traffic; rather, the slowdown resulted from high volumes of streaming video, which congested Internet links between the video content and the users themselves. Who is “at fault” for creating that congestion, who is responsible for mitigating that congestion, and who should pay to increase capacity are all important (and contentious) questions to which there are no simple answers. To say that “net neutrality” will fix this problem, however, reflects a fundamental misunderstanding. Below, I explain what actually caused the congestion, how the problem was ultimately resolved, and why the prevailing issue has more to do with Internet economics and market power than it does with policies like network neutrality.

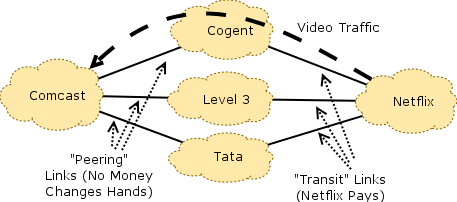

A (simplified) illustration of how Comcast users actually stream Netflix traffic (early 2013). Internet paths between consumers (“eyeballs”) and content typically traverse multiple Internet service providers. For example, prior to March 2014, there were several paths between Comcast and Netflix via multiple “transit providers”, including Cogent, Level 3, Tata, and others. In all of these cases, Netflix paid these transit providers for connectivity to Comcast customers. Comcast, in contrast, had what is called a “settlement-free peering” (or, “peering” for short) relationship with each of these transit providers, where Comcast and each of these providers deemed it mutually beneficial to interconnect.

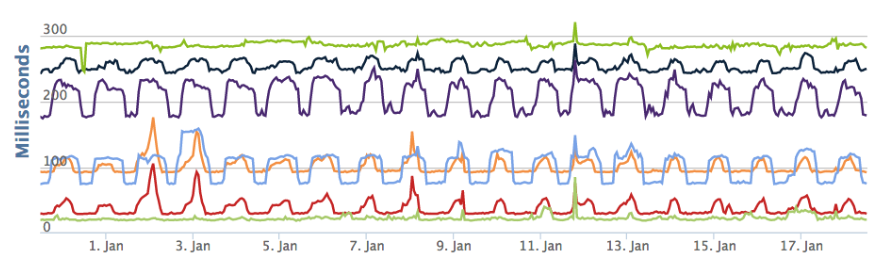

The Internet slows down (mid-2013 through early 2014). Around mid-2013, Comcast users (and other users) began to see congested Internet paths to various Internet destinations, not only to Netflix, but also to other Internet destinations. This phenomenon occurred because the video traffic was congesting paths not only to Netflix, but also paths to other destinations that had some path segments in common with paths to Netflix. In our ongoing BISmark project, we continually collect measurements from hundreds of home networks around the world. In mid-2013, we noticed and documented this congestion; our findings showed that this congestion, visible as extremely high latency, appeared on paths to many Internet destinations. The plot below shows an one consumer Internet connection that we measured in January 2014, which routinely experienced high latency to many Internet destinations every evening during “prime time”—oddly coinciding with peak video streaming hours from home networks. A “normal” latency plot would show flat lines, reflecting latencies that roughly correspond to the speed of light along that end-to-end path (plus small amounts of queueing). In contrast, the plot below shows striking diurnal latency spikes.

When we noticed this phenomenon, we raised it to Comcast’s attention. As it turns out, Comcast already knew about it, and it was clear how to solve the problem: Connect directly to Netflix with high-capacity links. The question was: who should pay for the interconnection? Comcast or Netflix?

The peering dispute: Who should pay? (late 2013 to early 2014) For a period of several months, while Comcast and Netflix were sorting out the answer to this question, Comcast customers experienced routinely high latency during peak hours, undoubtedly caused by congestion induced by video streaming. At this point (and as documented in opposing FCC filings), each side had a story to tell:

- Netflix claims that they were paying for transit to Comcast customers through their transit ISPs, and that they should not be responsible for upgrading the (congested) peering links between Comcast and the transit providers. The FCC declaration went so far as to claim that Comcast was intentionally letting peering links congest (see paragraph 29 of the declaration) to force Netflix to pay for direct connectivity. (Here is precisely where the confusion with net neutrality and paid prioritization comes into play, but this is not about paid prioritization, but rather about who should pay who for connectivity. More on that later.)

- Comcast claims that Netflix was sending traffic at such high volumes as to intentionally congest the links between different transit ISPs and Comcast, essentially taking a page from Norton’s “peering playbook” and forcing Comcast and its peers (i.e., the transit providers, Cogent, Level 3, Tata, and others) to upgrade capacity one-by-one, before sending traffic down a different path, congesting that, and forcing an upgrade. Their position was that Netflix was sending more traffic through these transit providers than the transit providers could handle, and thus that Netflix or their transit providers should pay to connect to Comcast directly. Comcast also implies that certain transit providers such as Cogent are likely the source of congested paths, a claim that has been explored but not yet conclusively proved one way or the other, owing to the difficulty of locating these points of congestion (more on that in a future post).

Resolving the dispute: Paid peering (March 2014). Both sides of this argument are reasonable and plausible—this is a classic “peering dispute”, which is nothing new on the Internet; in the past, these disputes have even partitioned the Internet, keeping some users on the Internet from communicating with others. The main difference in the recent peering dispute is that the stakes are higher. The loser of this argument is essentially who blinks first. The best technical solution (and what ultimately happened) is that Netflix and Comcast should interconnect directly. But, who should pay for that interconnection? Should Netflix pay Comcast, since Netflix depends on reaching its subscribers, many of whom are Comcast customers? Or, should Comcast pay Netflix, since Comcast subscribers would be unhappy with poor Netflix performance? This is where market leverage comes into play: Because most consumers do not have choice in broadband Internet providers, Comcast arguably (and, empirically speaking, as well) has more market leverage: They can afford to ask Netflix to pay for that direct link—a common Internet business relationship called paid peering—because they have more market power. This is exactly what happened, and once Netflix paid Comcast for the direct peering link, congestion was relieved and performance returned to normal. Note: Despite how popular media might present matters, this is not paid prioritization (which would amount to Comcast asking Netflix to pay for higher priority), but rather Internet economics that has borne itself out in peculiar ways because of the market structures.

Whether or not it is “right” that Comcast has such leverage is perhaps a philosophical debate, but it is also worth remembering that the classification of the Internet as an information service (regulation that the government is now backtracking on) is part of what got us into this situation in the first place. And, while it is also worth considering whether the impending merger between Comcast and Time Warner Cable might exacerbate the current situation, I predict that this is unlikely. In general, as one access ISP gains more market share, a content provider such as Netflix depends on connectivity to that ISP even more, potentially extracting increasingly higher prices for interconnection. In the specific case of Comcast and Time Warner, it is difficult to predict exactly how much additional leverage this will create, but as it turns out, these two ISPs are already in markets where they are not competing with one another, so this specific merger is unlikely to dramatically change the current situation.

Various technical and policy solutions could change the landscape, or at least mitigate these problems. Among them, fair queueing at interconnection points to ensure that one type of traffic does not clobber the performance of other traffic flows, might help mitigate some of these problems in the short term. The types of prioritization that the Open Internet Order deals with are, interestingly, one way of coping with congested links. Note that the Open Internet Order does not prohibit all prioritization, only paid prioritization. Thus, we will certainly see ISPs continue to use prioritization to manage congestion—prioritization is, in fact, a necessary tool for managing limited resources such as bandwidth. The real solution, however, likely has little to do with prioritization at all and more likely hinges on increased competition among access ISPs.

Leave a Reply