[Editor’s note: Tomorrow, Josh Goldstein is presenting on this topic as part of the CITP Luncheon Series, at the Woodrow Wilson School on Princeton’s campus. (12:10pm, in Robertson Hall room 023)]

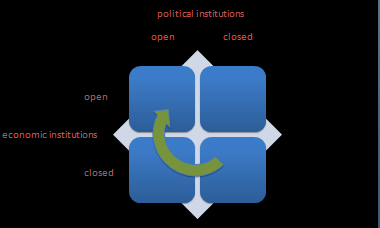

Around the world, societies generally agree that governments and bureaucrats should use the coercive power of the state, not to create extractive institutions that appropriate resources to the powerful elite, but rather to create inclusive institutions, which re-distribute political power and underpin economic institutions that provide incentive for investment and innovation (Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson 2004). The Open Government Partnership (OGP), a high-level political movement dedicated to transparency, responsiveness and accountability, is underpinned by the notion that institutions, rather than culture or geography, are the fundamental cause of long-run growth, and that inclusive politics shapes economic institutions, rather than the other way around.

Robert Bates (1981) classic study on agriculture price regulation in Latin America and Africa is a pre-Internet era illustration of this dynamic. Bates demonstrates that poor agriculture performance in post-independence Ghana was due to government controlled marketing boards systematically paying farmers lower prices than the market would bear in order to subsidize the cost of living, and ultimately earn the votes, of those living in urban areas. In Colombia, however, the two main political parties were in competition for the votes of small cocoa farmers, so payments to farmers were much higher, resulting in sustained economic performance. In this case, political power shaped economic institutions which in turn shaped economic outcomes.

chart adapted from Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson (2004)

Political institutions are endogenous and historically contingent, so there are no policy formulas for shifting from extractive to inclusive institutions. In Why Nations Fail (2012), Acemoglu and Robinson point to Seretse Khama, the first president of Botswana, who built on the equitable institutions already existing in the protectorate of Bechuanaland. Khama was unusually dedicated to adapting the traditional institutions to the modern world. Botswana’s economic and political success stemmed both from existing institutions and historical contingencies.

Acemoglu and Robinson call the slow and incremental way that nations become more inclusive the virtuous circle. This feedback loop works through three related mechanisms: (i) eliminating the most egregious extractive relations, thus reducing the benefits one might gain from capturing the political process; (ii) entrenching the rule of law, introducing the idea that people should be equal before the law but also in the political system; and (iii) improving the free flow of information, allowing individuals to more easily mobilize against threats to inclusiveness.

It is at least plausible that such political transitions are not be possible today without the use of information and communication technologies. The movement for open government aims to help promote the virtuous circle: changing norms by encouraging citizens to recognize extractive institutions when they see them, and holding the state’s agent accountable through the use of real-time performance data, streamlined access to information, and tools for citizens to monitor actions of the state.

Fifty-seven national governments have made commitment to this approach by joining OGP and articulating specific commitments to transparency, responsiveness and accountability. Yet presidential-level commitment is likely insufficient for creating inclusive political institution, in part because truly inclusive institutions mean that individuals in all levels of government might enjoy fewer privileges and control less of the nation’s resources.

Unsurprisingly, execution on open government commitments, though still in its earliest stages, has been highly uneven, with a small number of government line agencies or ministries leading on this process. Huber & McCarty (2004) articulate a bureaucratic “trap” that explains how even if administrative or ministry leaders have the expertise to make their services more inclusive, bad bureaucracies make this difficult. In many developing countries, not only are bureaucracies inefficient (poor at implementing the goals they set out to achieve), but they are also hard to control because their incompetence diminishes the incentives to implement policy reforms, and increases the incentives for administrative leaders to make decisions based on political rewards rather than effectiveness.

What is surprising is that some leaders do manage to escape this trap and make institutions more inclusive. While the incremental and historically contingent nature of institutional change make it notoriously difficult to study, it may be possible to learn from instances where leaders and other citizens have escaped from this trap and contributed to the virtuous circle. The Government of Moldova, led by liberal democratic Moldova Alliance, launched an open data portal in 2011, publishing performance data about the four most demanded public services, as well as income declarations for civil servants and public officials. In 1998 in Porto Alegre, Brazil, leaders built on a long tradition of participatory budgeting to use mobile and web interface to engage citizens in the distribution of resources. This year in Kenya, government data holders are responding to demands from software developers and citizens groups to release data in ways that will help parents compare school performance data and make relevant choices for their children.

The literature presents a number of plausible explanations for why administrative and ministry leaders are able to escape from this trap: insulation from patronage (Geddes 1990), the nature of social networks amongst bureaucrats (Carpenter 2001), and capacity programs (McCourt & Sola 1999). By unpacking the dynamics of what motivates actors participating in these efforts at the micro level, I seek to develop a logically coherent and testable theory to account for how government leaders use technology to transition from extractive institutions, that leave the majority of population with poor services and few opportunities, to inclusive institutions that level the playing field, increase access to services, and create incentives for innovation and growth.