[Huge thanks to Dillon Reisman, Arvind Narayanan, and Joanna Huey for providing great feedback on early drafts.]

LinkedIn makes the primary email address associated with an account visible to all direct connections, as well as to people who have your email address in their contacts lists. By default, the primary email address is the one that was used to sign up for LinkedIn. While the primary address may be changed to another email in your account settings, there is no way to prevent your contacts from visiting your profile and viewing there whatever email you chose to be primary. In addition, the current data archive export feature of LinkedIn allows users to download their connections’ email addresses in bulk. It seems that the archive export includes all emails associated with an account, not just the one designated as primary.

It appears that many of these addresses are personal, rather than professional. This post uses the contextual integrity (CI) privacy framework to consider whether the access given by LinkedIn violates the privacy norms of using a professional online social network.

At the moment, LinkedIn users can see their contacts’ email addresses by clicking “Show more” on in the “Contact and Personal Info” section at the upper right of those contacts’ profiles. In addition, users can request an archive of data in their LinkedIn settings.

The LinkedIn help page informs:

Within minutes, you’ll receive an email with a link where you can download certain categories of personal information we have for you, including your messages, connections, and contacts. This is information that’s fastest to compile.

Within 24 hours, we’ll send you a second email with a link where you can download your full archive, including your activity and account history.

The file for your contacts includes their email addresses. A quick look at my personal contacts revealed that over half of them use presumably personal email accounts, such as those from Gmail, Yahoo, and Hotmail.

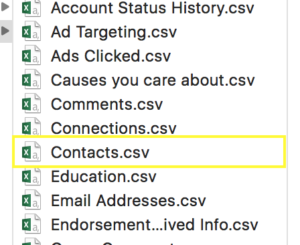

The contacts.csv file, which is included in the exported data, reveals the emails your contacts use to log on to LinkedIn.

Privacy in Context

Do my connections expect their personal emails to be revealed? This, in my opinion, is an ideal case to examine through the lens of Helen Nissenbaum’s contextual integrity (CI) theory.

Nissenbaum’s theory recognizes that information privacy depends on the context in which the information flows. The informational flow is valid if it conforms to the existing norms within a given context.

Contextual norms may be explicitly expressed in rules or laws or implicitly embodied in convention, practice, or merely conceptions of “normal” behavior. A common thesis in most accounts is that spheres are characterized by distinctive internal structures, ontologies, teleologies, and norms.

— Helen Nissenbaum, Respect for context as a Benchmark for privacy online: what it is and isn’t.

The CI framework provides a way to express an existing contextual norm using a 5-parameter tuple: (sender, attribute, subject, recipient, transmission principle).

Sender indicates from where the information flow originates. Attribute describes what information is being conveyed. Subject captures who or what the information is about. Recipient is where the conveyed information ends up. Transmission principle (TP) is a constraint imposed on the information flow.

A contextual informational norm is breached when changes occur in any of the parameters. For example, in a medical context, you (sender and subject), as a patient, might expect to share information on a medical condition (attribute) with your doctor (recipient) in a secure manner (TP). So when your medical information ends up with your colleague instead (i.e., changing the recipient parameter), the contextual norm is breached and your privacy expectation is potentially violated.

Privacy Expectations and LinkedIn

Let’s examine the feature of exposing personal emails of LinkedIn connections through the CI lens and see how it might be problematic.

LinkedIn is a social network that “connects the world’s professionals,” and many members have over 500 connections. However, many connections are not deep or even based in any real-world relationship: people add contacts quite easily without much vetting.

I personally view LinkedIn as a professional network and prefer to separate business and personal communication. So when I use LinkedIn to reflect my professional affiliations and when I communicate through the platform, I expect to do it on a professional level. I don’t expect personal information such as my personal email to be revealed to a contact without my explicit consent.

Through the CI theory, my norm can be captured as:

LinkedIn (sender) —> my (subject) personal email (attribute) —> contact (recipient), only with my explicit consent (transmission principle)

A change to any of the CI parameters potentially leads to a violation of privacy. So for me, my privacy expectations are violated by the change in transmission principle, as LinkedIn provides my personal email to a contact without my explicit consent. I presume other LinkedIn users might feel the same.

Over half of my contacts use their personal emails: out of 571 entries (some users have multiple emails, indicating that more than primary emails are provided), 269 used Gmail, 21 used Yahoo and 16 used Hotmail, and more used a variety of other personal email providers. I suspect many of them do not realize that these emails are being revealed to their contacts and that some of that group share my privacy norm.

When it comes to revealing personal emails, this is not the first time LinkedIn has been accused of violating users’ privacy expectations. In the previous version of its InMail service, you had to actively opt-out from revealing your email address. Now that the company has moved away from email-like communication towards messaging, this “feature” was removed.

In another reported incident, it was possible to find out contacts’ email addresses by exploiting the syncing contacts feature because “LinkedIn assume[d] that if an email address is in your contacts list, that you must already know this person.”

These examples demonstrate how a company’s assumptions and business goals can drive design decisions that lead to implementations in violation of users’ privacy expectations. While these decisions are not easy to get right (see Facebook’s public listing search and Google Buzz), the violations suggest the lack of a robust privacy framework guiding the design.

Using my personal e-mail fits in my expectations for LinkedIn. Showing my work e-mail as my primary contact would violate my expectations of LinkedIn.

The information on LinkedIn is about me and my career, not about my current position. My work e-mail is a transient and a reflection of my current job, not about me or my career.

In addition to that philosophical stand, many contacts received via LinkedIn are about new positions. I certainly don’t want those messages being sent through the e-mail system of my current employer.

The email that is included in the export is the primary email address which is also used to log into a user’s LinkedIn account. This may be a cause for additional concern. However, it is up to the user to provide and verify additional email addresses including their work email address.

It is likely that the user leaves the default email address set to their personal email address because of the risk of losing login access to their LinkedIn account should they forget their password and lose access to their work email account.

Personally, I feel the burden is on the user. It’s important to remember that the user doesn’t own their work email account. Their employer does.