How are data science and open science movement transforming how researchers manage research ethics? And how are these changes influencing public trust in social research?

I’m here at the Center for IT Policy to hear a talk by Edward P. Freeland. Edward is the associate director of the Princeton University Survey Research Center and a lecturer at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Edward has been a member of Princeton’s Institutional Review Board since 2005 and currently serves as chair.

Edward starts out by telling us about about his family’s annual Christmas card. Every year, his family loses track of a few people, and he ends up having to try to track someone down. For several years, they sent the postcard to Ed’s wife’s cousin Billy to someone in Hartford CT, but it turns out that the address was not their cousin Billy but a retired neurosurgeon. To resolve this problem this year, Edward and his wife filled out more information about their family members into an app. Along the way, he learned just how much information about people is available on the internet. While technology makes it possible to keep track of family members more easily, some of that data might be more than people want to be known.

How does this relate to research ethics? Edward tells us about the principles that currently shape research ethics in the United States. These principles come from the 1978 Belmont Report, which was prompted in party by the Tuskeegee Syphilis Study, a horrifying medical study that ran for forty years. In the US, universities now have to do research focused on respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

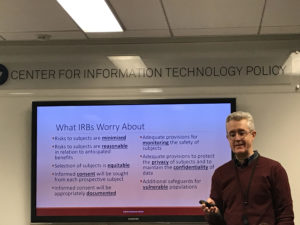

In practice, what do university ethics boards (IRBs) care about? Edward and his colleagues compiled a list of the issues that ethics boards into a single slide:

When it comes to privacy, what to university ethics boards care about? Federal regulations focus on any disclosure of the human subjects’ responses outside of the research and the risk that it would expose people to. In practice, the ethics board expects researchers to adopt procedural safeguards around who can access data and how it’s protected.

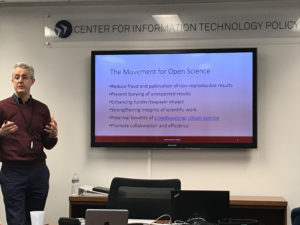

In the past, studies would basically conclude after the researchers publish the research. But the practice of research has been changing. Advocates of open science have worked to reduce fraud, prevent burying of unexpected results, enhance funder/taxpayer impact, strengthen, the integrity of scientific work, work through crowdsourcing or citizen science, and collaborate in new ways. Edward tells about the Open Science Collaboration, which tried in 2015 to replicate a hundred studies from across psychology, and who often failed to do so. Now others are trying to ask similar questions across other fields including cancer research.

In just a few years, the Center for Open Science has supported many researchers and journals to pre-register and publish the details of their research. Other organizations are also developing similar initiatives, such as clinicaltrials.gov.

Many in the open science movement suggest that researchers archive and share data, even after submitting a manuscript. Some people use a data sharing agreement to protect data used by others. Others prepare datafiles from their research for public use. But publishing data introduces privacy risks for participants in research. While US legislation HIPAA covers medical data, there aren’t authoritative norms or guidelines around sharing that data.

Many people turn to anonymization as a way to protect the information of people who participate in research. But does it really work? The landscape of data re-identification is changing from year to year, but the consensus is that anonymization doesn’t tend to work. As Matt Salganik points out in his book Bit By Bit, we should assume that all data are potentially identifiable and potentially sensitive. Where might we need to be concerned about potential problems?

- People are sometimes recruited to join survey panels where they answer many questions over the years. Because this data is highly-dimensional, it may be very easy to re-identify people

- Distributed anonymous workforces like Amazon Mechanical Turk also represent a privacy risk. The ID codes aren’t anonymous: you can google people’s IDs and find people’s comments on various Amazon products

- Re-identification attacks, which draw together data from many sources to find someone, are becoming more common

Public Confidence in Science

How we treat people’s data affects public confidence in science– not only how people interpret what we learn, but also people’s likelihood to participate in research. Edward tells us that survey response rates have been dropping, even when surveys are conducted by the government. American society has always had a fringe movement of people who resisted government data collection. If those people gain access to the levers of power, they may be able to influence the government’s likelihood to collect data that could inform the public on important issues.

Edward tells us that very few people expect their data to be kept private and secure, according to research by Pew. When combined with declining trust in institutions, concerns about privacy may be one reason that fewer people are responding to surveys.

At the same time, many people are organizing to try to resist surveying by the US government. Some political and activist groups have been filming their interactions with survey collectors, harassing them, and claiming that researchers or the government have secret. As researchers try to uphold public trust by doing trustworthy, beneficial research, we need to be aware of the social and political forces that influence how people think about research.