All voting machines these days are computers, and any voting machine that is a computer can be hacked to cheat. The widely accepted solution is to use voting machines to count paper ballots, and do Risk-Limiting Audits: random-sample inspections of those paper ballots to ensure (with a guaranteed level of assurance) that the election outcome claimed by the computers is the same as you’d get by an accurate count of the votes actually marked on the paper ballots.

An RLA is any statistical/logistical method that guarantees a quantifiable risk limit. Most RLA methods are much more efficient than a full recount, but some RLA methods are more efficient than others, especially in close elections: the closer the margin of victory, the more ballots you have to random-sample to guarantee the risk limit. One simple method, the Ballot Polling Audit, randomly samples individual ballots from among all the batches of ballots in the entire election, and (by human inspection of the paper ballot) counts how many are for each candidate. If you sample enough ballots, and that “poll” comes out the same way as the outcome claimed by the voting machines, then you get real assurance. (If the “poll” doesn’t come out the same way, you can do a bigger poll or a full hand recount.)

If the margin of victory is large (60/40 or even 55/45), then a Ballot Polling Audit may need to sample only a few hundred ballots, even if a million votes were cast. But if the margin is closer than 1% then a BPA may need to sample tens of thousands of ballots, or in some cases over a hundred thousand.

A more high-tech RLA, the Ballot-level Comparison Audit, can be much more efficient. The optical-scan voting machine must print onto each ballot a unique serial number;* it must produce an electronic data file of Cast Vote Records (CVR file) which lists every ballot, with its serial number and exactly which votes are claimed to be on the corresponding physical paper ballot. The the audit consists of: add up the CVR file to check the outcome, sort the CVR file to make sure there are no duplicate serial numbers, and take a small random sample of serial numbers from the CVR file, find the corresponding physical paper ballots, and make sure the CVR file makes an accurate claim about what’s on the paper. And even if the margin is close, checking just a few hundred ballots can give very high confidence.

*This can be done without printed serial numbers; see below for an alternate method.

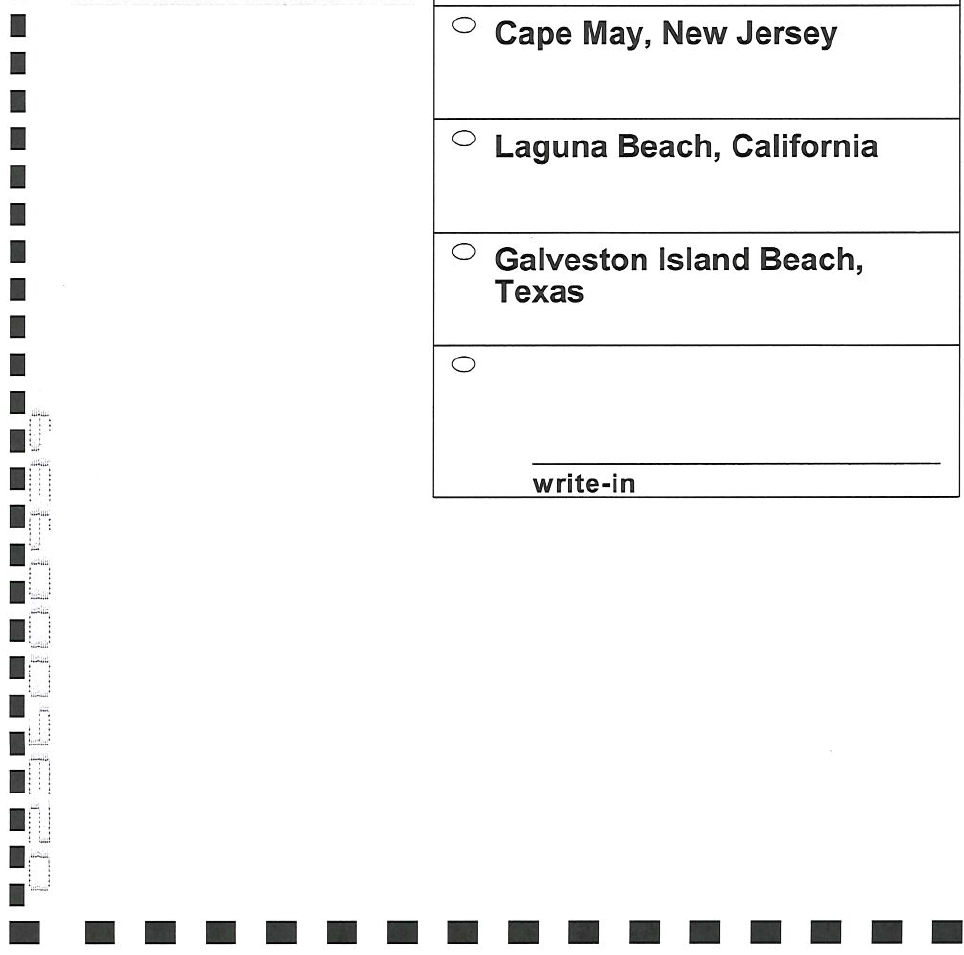

The voter should not see the serial number–otherwise there is no “secret ballot”, and voters could be bribed or coerced to vote a certain way. Therefore, the optical-scan voting machine should print the serial number onto the ballot after the voter last sees the ballot. Because that optical-scan voting machine could itself be hacked, it’s essential to ensure that the serial-number printer is physically incapable of printing votes onto the ballot, even if the machine’s software is entirely replace. That’s not hard: an optical scanner can be outfitted with a tiny printer that can print only in the left-hand 1-centimeter margin of the paper, so it can’t possibly print votes beyond the margin. Here’s an example; the serial number at lower-left was added by the optical scanner:

Modern Central-Count Optical Scan (CCOS) voting machines from several vendors have this essential capability: print a unique serial number onto each ballot as it is scanned, and record that number in the CVR file. Therefore, jurisdictions that use central-count optical scan can already do efficient RLAs, and some jurisdictions are already doing them.

Ballot-comparison audits have also been done with CCOS equipment that does not print serial numbers. They rely on the fact that the CCOS scanner preserves the exact order of a batch of ballot papers. Ballots are divided into small batches (such as 200 sheets) for scanning. Based on the CVR file, the human auditor may be instructed to find the 119th sheet in the batch.

Central-count optical scan is used for mail-in ballots, and for ballots marked in polling places where the voters deposit ballots in ballot boxes for transport to a central location where a high-speed CCOS machine tabulates them.

But many jurisdictions use Precinct-Count Optical Scan (PCOS): voters mark their ballots and insert them directly into a scanner that scans the ballot, tabulates the votes, and deposits the ballot into a ballot box (preserving it for later audits and recounts). In such systems, the story about serial numbers and ballot-level comparison audits is more complicated, as I will describe in the next article.