My previous article explained why it’s a bad practice, used in some election offices, to open absentee ballot envelopes before sorting them by precinct (or ballot-style). Those jurisdictions rely on the ballot-style barcode, printed on the optical-scan ballot, that tells the Central Count Optical Scan (CCOS) voting machine what’s on the ballot. In that system, the paper ballots never get sorted at all; only their electronic images are sorted by the scanner’s computer programs.

As I explained, there are significant advantages to physically sorting the absentee-ballot envelopes into precincts, before opening them. But how can that be done efficiently? I spoke to Boris Brajkovic, the Election Director of Montgomery County, Maryland, who described their handling of mail-in ballots. In the 2022 general election, they handled 118,530 mail-in ballots this way (there were also 158,641 election-day ballots, 55,717 early-vote-center ballots, and 13,879 provisional ballots).

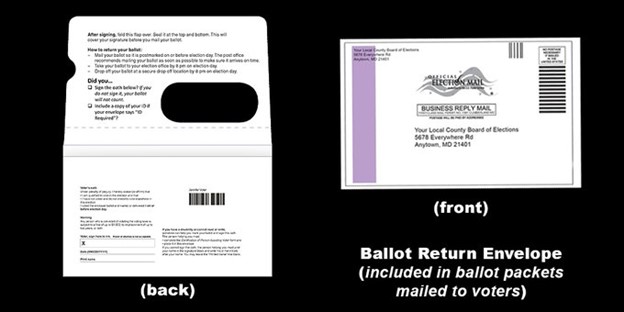

The ballot-return envelope has a bar-code identifying the specific voter, along with a space for the voter’s signature and date.

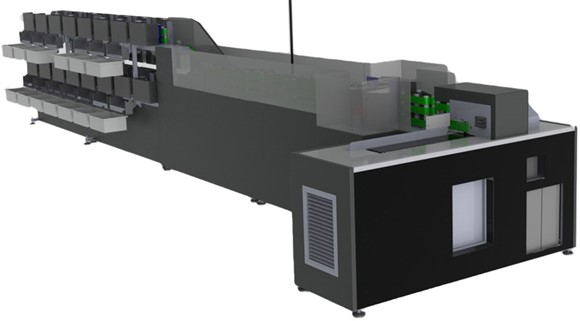

In the weeks before the election, as each batch of ballots is collected from the Post Office, from dropboxes, or from walk-ins at the Elections office, the envelopes are fed through a high-speed sorting machine that scans the bar code, looks up the voter’s precinct, and sorts the envelope into a bin. (But 13% of the mail-in/dropbox ballots arrive in voter-supplied envelopes, without barcodes, that are sorted by hand.)

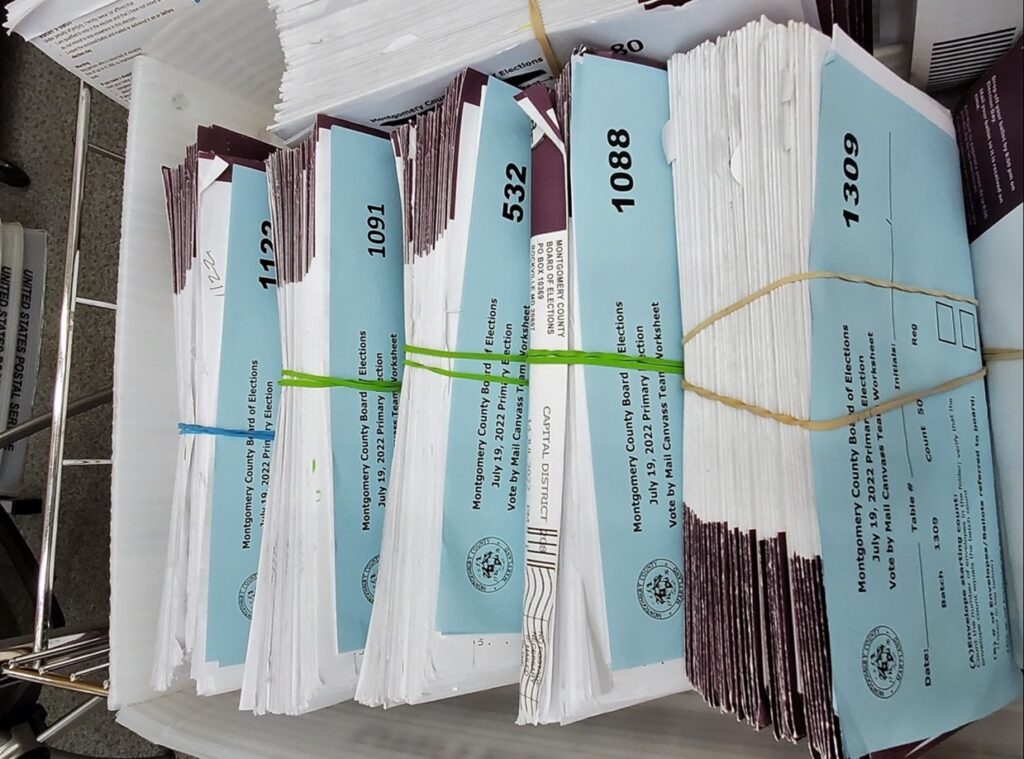

Montgomery County’s high-speed sorter has 30 bins, and there are 258 precincts in the county, so most envelopes make two trips through the sorter. The result is, bundles of ballots, each bundle with the same ballot-style number (based on precinct), with a blue “batch sheet” on which that number is prominently printed, along with a count of how many envelopes are in that bundle. The sorter will also update the ballot-tracking database to indicate that the ballot is received; the voter can track this online.

The next step is to open the envelopes. Teams of two Election Judges (permanent or temporary employees of the Board of Elections, one Democrat and one Republican per team) take a bundle of ballots. They place the “batch sheet” face-up so they can refer to the ballot-style number. For each envelope, they check that the signature is present; they flip the envelope upside-down to hide the voter-identifying information; they open the envelope and remove the optical-scan ballot; they check that it’s got the right ballot-style number (matching the number on the blue sheet); and they visually check for overvotes and ambiguous marks. For example, if the voter has filled in an oval, then crossed it out and filled in another oval, this ballot will have to go to an adjudication board to be interpreted. Finally, they put the ballots into a box reserved for that ballot-style; they put the envelopes into a bundle with the batch sheet.

Sometimes it happens—perhaps 5 or 10 times in 100,000 envelopes—that the optical-scan ballot in the envelope has a ballot-style number that doesn’t match the barcode on the outside of the envelope. Then the election administrators track down what happened. Typically, it’s that friends or relatives (from different precincts) sat down together to fill out their absentee ballots, and inadvertently swapped envelopes.

All this ballot-processing can be done up to 20 days before the election. But actual counting of the ballots is not done until Election Day or just before. The batches of ballots, separated by ballot style, are fed through the central-count optical scanner (CCOS). For each stack, the CCOS reports how many ballots it scanned, and from which ballot styles. If this doesn’t match the information on the batch-sheet (perhaps two ballots got stuck together), then they investigate and reconcile. The equipment is programmed not to release any vote totals in pre-election-day scanning.

In summary, this is a well organized sort-then-scan procedure. If someone tried any funny business with putting the wrong ballot-style into their envelope, they’d get caught right away—before the ballot is separated from the envelope. If a candidate needed a recount, the batches of ballots are all presorted, ready to go. That is, the mail-in (or dropbox) ballots are presorted. And the election-day ballots are sorted by precinct, because they were cast in the individual precincts. But the early-vote-center ballots are not physically sorted by precinct. In any hypothetical recount of paper ballots, the 55,000 Early Voting Center ballots would have to be sorted. It is not clear how Maryland’s recount procedures handle the sorting of those ballots, or who pays for it; that question has been a significant issue in other states, as I described in my previous article.

Next part in this series: Expensive and ineffective recounts in Los Angeles County

This does not provide for ballot privacy. “For each envelope, they check that the signature is present; they flip the envelope upside-down to hide the voter-identifying information; they open the envelope and remove the optical-scan ballot; they check that it’s got the right ballot-style number (matching the number on the blue sheet); and they visually check for overvotes and ambiguous marks.” First, in some jurisdictions the declaration envelope has the signature on one side and the voter’s name & return address on the other side (which is used for mailing). Second, it’s not that hard to hold one name in memory for a short amount of time between learning the voter’s name and seeing their ballot choices. This allows vote-buying and other forms of coercion to be effective and enforced. I am not familiar with the extent MD law attempts to ensure ballot secrecy, but this can be a problem in other places.

“All this ballot-processing can be done up to 20 days before the election…The equipment is programmed not to release any vote totals in pre-election-day scanning.” Again, with this work happening in advance, the humans involved may get a pretty good sense of who’s winning by how much well before election day, and that valuable information sometimes leaks and can affect election outcomes.

“If someone tried any funny business with putting the wrong ballot-style into their envelope, they’d get caught right away—” I wonder what percentage of time this is due to the voter having been given the wrong ballot by the officials or mail ballot vendor. That is also known to happen, sometimes at fairly large scale, from time to time, not caught by officials or formal review processes unless enough astute voters call attention to the problem to be believed (example: https://www.wesa.fm/politics-government/2020-10-14/printing-error-sends-wrong-ballots-to-nearly-29-000-voters-in-allegheny-county).

There are two ways this first issue seems readily addressable. One way is to have the style-identifying markings, and ONLY those, visible through a secrecy envelope window, but this may be hard to pull off in practice. Another way is that if you sort ballots by precinct as suggested in the prior article, then separate the ballots-in-secrecy-envelopes from their voter-identifying declaration envelopes and mix them up well, then open those and they should all be the same precinct. If they are not, you only count the contests which appear on both the present and the correct ballot.

For the second issue, the sorting by precinct can be done in advance of election day and the opening and counting could start at some time on election day. The described system also suffers from the coercion issue of counting only the first ballot submitted by each voter instead of the last; voters should be able to override a coerced postal ballot with one submitted later (and in some places, even an in-person vote on election day). This could somewhat delay results announcement, but at significantly better value in terms of a trustworthy election.