By Kevin Lee and Arvind Narayanan

35 million phone numbers are disconnected every year in the U.S., according to the Federal Communications Commission. Most of these numbers are not disconnected forever; after a while, carriers reassign them to new subscribers. Through the years, these new subscribers have sometimes reported receiving calls and messages meant for previous owners, as well as discovering that their number is already tied to existing accounts online.

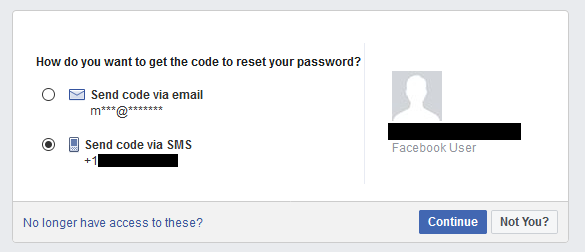

While these new owner mixups may make for interesting dinner party stories, number recycling presents security and privacy issues as well. If a recycled number remains on a previous owner’s recovery settings for an online account, the adversary can obtain that number and break into that account. The adversary can also use that phone number to look for your other personally identifiable information online, and then impersonate you with that phone number and PII. These attacks have been talked about through anecdotes and speculation, but never thoroughly investigated.

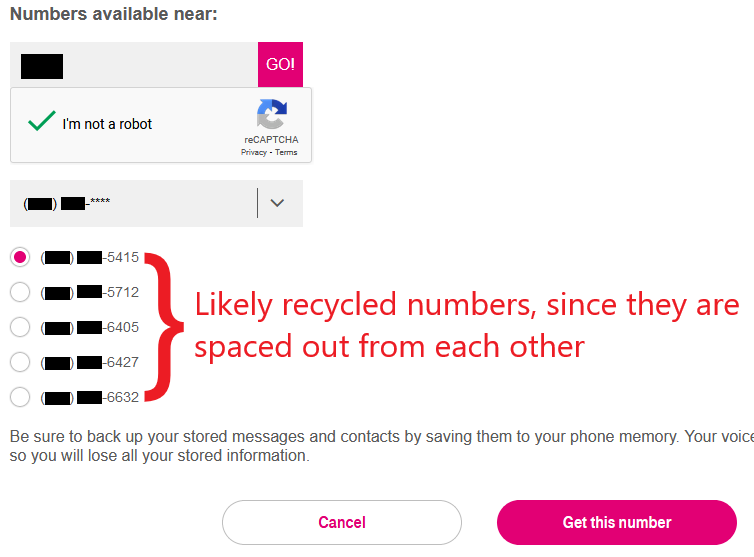

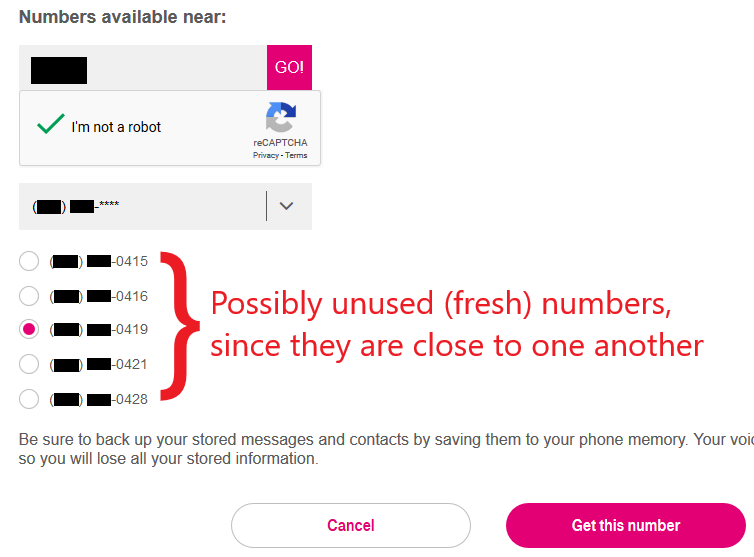

In a new study, we empirically evaluated number recycling risks in the United States. We sampled 259 phone numbers available to new subscribers at two major carriers, and found that 215 of them were recycled and vulnerable to either account hijackings or PII indexing—the two scenarios we described prior. We estimated the inventory of available recycled numbers at one carrier to be about one million, with a largely fresh set of numbers becoming available every month. We also found design weaknesses in carriers’ online interfaces and number recycling policies that could facilitate number recycling attacks. Finally, we obtained 200 numbers from both carriers and monitored incoming communication. In just one week, we found 19 of the 200 numbers in the honeypot were still receiving sensitive communication meant for previous owners, such as authentication passcodes and calls from pharmacies.

Phone number recycling is a standard industry practice regulated by the FCC. There are only so many valid 10-digit phone numbers, which are allocated to carriers in blocks to individually assign to their subscribers. Eventually, there will be no more blocks to allocate to carriers; when that happens, expansion will essentially be capped. To prolong the usefulness of 10-digit dialing (think of all the systems that need replacing if we suddenly switch to 11 digits!), the FCC not only has strict requirements for carriers requesting new blocks, but also instructs them to reassign numbers from disconnected subscribers to new subscribers after a certain timeframe (45 to 90 days). Number recycling is one of the reasons we have been able to put off this doomsday scenario from 2005 to beyond 2050. It is also the reason vulnerable numbers—and number recycling threats—are so prevalent.

In our paper, we recommend steps carriers, websites, and subscribers can take to reduce risk. For subscribers looking to change numbers, our primary recommendation is to park the number to use as an inexpensive secondary line. By doing so, subscribers can mitigate some of the threats from number recycling. Last October, we responsibly disclosed our findings to the carriers we studied and to CTIA—the U.S. trade association representing the wireless telecommunications industry. In December, both carriers responded by updating their number change support pages to clarify their number recycling policies and remind subscribers to update their online accounts after a number change. Although this is a step in the right direction, more work can be done by all stakeholders to illuminate and mitigate the issues.

Our paper draft is located at recyclednumbers.cs.princeton.edu.