On Monday, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) released a decision that effectively bans “zero-rated” Internet services in the country. While the notion of zero-rating might be somewhat new to many readers in the United States, the practice is common in many developing economies. Essentially, it is the practice by which a carrier creates an arrangement whereby its customers are not charged normal data rates for accessing certain content.

High-profile instances of zero-rating include Facebook’s “Free Basics” (formerly “Internet.org“) and Wikipedia Zero. But, many readers might be surprised to learn that the practice is impressively widespread. Although comprehensive documentation is hard to come by, experience and conventional wisdom affirm that mobile data carriers in regions across the world regularly partner with mobile data providers to provide services that are effectively free to the consumer, and these offerings tend to change frequently.

I experienced zero-rating first-hand on a trip to South Africa last summer. While on a research trip there, I learned that Cell C, a mobile telecom provider, had partnered with Internet.org to offer its subscribers free access to a limited set of sites through the Internet.org mobile application. I immediately wondered whether a citizen’s socioeconomic class could affect Internet usage—and, as a consequence, their access to information.

Zero-rating evokes a wide range of (strong) opinions (emphasis on “opinion”). Mark Zuckerberg would have us believe that Free Basics is a way to bring the Internet to the next billion people, where the alternative might be that this demographic might not have access to the Internet at all. This, of course, presumes that we equate “access to Facebook” with “access to the Internet”—something which at least one study has shown can occur (and is perhaps even more cause for concern). Others have argued that zero-rated services violate network neutrality principles and could also result in the creation of walled gardens where citizens’ Internet access might be brokered by a few large and powerful organizations.

And yet, while the arguments on zero-rating are loud, emotional, and increasingly higher-stakes, these opinions on either side have yet to be supported by any actual data.

We Must Bring Data to this Debate

Unfortunately, there is essentially no data concerning the central question of how users adjust their behavior in response to mobile data pricing practices. Erik Stallman’s eloquent post today on the TRAI ruling and the Center for Democracy and Technology‘s recent white paper on zero-rating both lament the lack of data on either side of the debate.

I want to change that. To this end, as Internet measurement researchers and policy-interested computer scientists, we are starting to bring some data to this debate—although we still have a long way to go.

As luck would have it, we had already been gathering some data that shed some light on this question. In 2013, we developed a mobile performance measurement application, My Speed Test, which performs speed test measurements of a user’s mobile network, but also gathers information about a user’s application usage, and whether that usage occurs on the cellular data network or on a Wi-Fi network. My Speed Test has been installed on thousands of phones in several hundred countries around the world over this three-year period. In addition to a significant based of installations in the United States, we had several hundred users running the application in South Africa, due to a study of mobile network performance that we performed in the country a couple of years ago.

This deployment gave us a unique opportunity to study the application usage patterns of a group of users, across a wide range of carriers, across countries, over three years. It allowed us to look at usage patterns in the United States (where many users are on pre-paid plans) to South Africa (where most users are on pre-paid, pay-as-you-go plans). It also allowed us to look at how users responded to zero-rated services in South Africa. A superstar undergraduate student, Ava Chen, led this research in collaboration with Enrico Calandro at Research ICT Africa and Sarthak Grover, a Ph.D. student here at Princeton. I briefly summarize some of Ava’s results below.

The results of this study are preliminary. More widespread deployment of My Speed Test would ultimately allow us to gather more data and draw more conclusive results. We can use your help by spreading the word about our work, and My Speed Test.

Effects of Zero Rating on Usage

We explored the extent to which the zero-rating offerings of various South African carriers affected usage patterns for different applications. During our data-collection period, mobile data provider Cell C offered its customers several zero-rating packages:

- From November 19, 2014 to August 31, 2015, Cell C zero-rated WhatsApp. From September 1, 2015 until now, Cell C adopted a bundle offer where, for a fee of ZAR 5 (about $0.30), users could use up to 1 GB on WhatsApp for 30 days, including voice calls.

- On July 1, 2015, Cell C began zero-rating Facebook’s Free Basics service.

- On two separate occasions—May 1–July 31, 2014 and August 1, 2014–February 13, 2015—MTN zero-rated Twitter.

We aimed to determine whether users adjusted their mobile behavior in response to these various pricing promotions. We found the following trends:

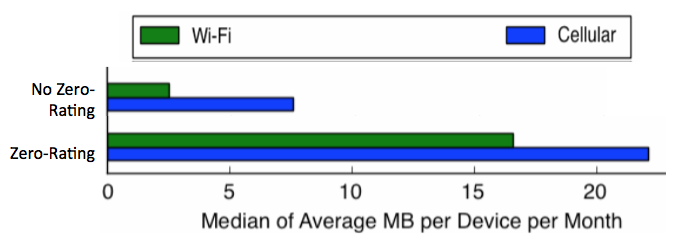

Cell C users increased WhatsApp usage by more than a factor of three on both cellular and Wi-Fi. The average monthly user for Cell C increased WhatsApp usage on the cellular network by a factor of three, from about 7 MB per month to about 22 MB per month on average. Interestingly, not only did the usage of WhatsApp on the cellular network increased, usage also increased on Wi-Fi networks, by more than a factor of seven—to about 17 MB per month. Interestingly, users still used WhatsApp more on the cellular data network than on Wi-Fi.

Cell C usage on WhatsApp increased on both WiFi and cellular in response to zero-rating a zero-rating offering from the carrier.

Twitter usage on MTN increased in response to zero-rating. We limited our analysis of MTN’s zero-rating practices to 2014, because we did not have enough data to draw conclusive results from the second period. Our analysis of the 2014 period, however, found that aside from the holiday season (when Twitter traffic is known to spike due to shopping promotions), the second most significant spike in usage on MTN occurred during the period from May through July 2014 when the zero-rating promotion was in effect. During this period the average Twitter user on MTN exchanged as much as 40 MB per day on Twitter, whereas usage outside of the promotional period was typically closer to about 10 MB per day.

Other Responses to Mobile Data Pricing

Mobile users in the United States use more mobile data, on both cellular and Wi-Fi. Mobile users in both the United States and South Africa used YouTube and Facebook extensively; other applications were more specific to country. We noticed some interesting trends. First, when looking at the total data usage for these applications in each country, the median user in the United States tended to use more data per month, not only on the cellular data network but also on Wi-Fi networks. It is understandable that South African users would be far more conservative with their use of cellular data; previous studies have noted this effect. It is remarkable, however, that these users also were more conservative with their data usage on Wi-Fi networks; this effect could also be explained that even Wi-Fi and wired Internet connections are still considerably more expensive (and more of a luxury good) than they seem to be in the United States. In contrast, users in the United States not only used more data in general, but they often used more data on average on cellular data networks than on Wi-Fi—perhaps as a result of the fact that users in the US were much less sensitive to the cost of mobile data than those in South Africa.

Mobile users in South Africa exchanged significantly more Facebook traffic than streaming video traffic—even when on cellular data plans. Given the high cost of cellular data in South Africa, we expected that users would be conservative with mobile data usage in general. Although our findings mostly confirmed this, Facebook was a notable exception: Not only did the typical user consume significantly more traffic using Facebook than with streaming video, users also exchanged more Facebook traffic over the cellular network than they did on Wi-Fi networks. This behavior suggests that Facebook usage is dominant to the extent that users appear to be more willing to pay for relatively expensive mobile data to use it than they are for other applications.

Summary and Request for Help

Our preliminary evidence suggests that zero-rated pricing structures may have an effect on usage of an application—not only on the cellular network where pricing instruments are implemented, but also in general. However, we need more data to draw stronger conclusions. We are actively seeking collaborations to help us deploy My Speed Test on a larger scale, to facilitate a larger-scale analysis.

To this end, we are excited to announce a collaboration with the Alliance for an Affordable Internet (A4AI) to use My Speed Test to study these effects in other countries on a larger scale. We are interested in gathering more widespread longitudinal data on this topic, through both organic installations of the application or studies with targeted recruitment.

Please let me know if you would like to help us in this important effort!

I must say this result isn’t at all surprising. I mean, I assume Facebook already knows a lot more about how their usage changes when zero-rated than we do. If they found that paying huge sums of money to cell providers in order to get zero-rated was not in fact increasing usage, that money spigot would turn off pretty quick.

Do results have to be surprising to be important? This is science!

If a result matches your intuition, that’s perhaps reassuring, but I’m not sure what your point is. That doesn’t diminish the importance of bringing data to this debate.

What Facebook “already knows” is not really relevant to the results. Facebook is unlikely to ever release any of their data, and whatever they do decide to say (if anything) is certainly punctuated by their own agenda. Let me know, though, if they ever approach you with data. We’d be happy to study these questions with a larger dataset, which was part of the point of the post.

It was not clear from the article if zero-rating boosted overall data consumption and not just for the particular apps. Also, US vs S. Africa comparisons are less relevant than say those of established OECD or European countries.

The debate over zero rating and net neutrality is flawed to begin with. There are actually 3 separate issues here:

1) lack of settlements that provide necessary price signals to coordinate investment across networks and clear supply and demand efficiently

2) the differences in demand elasticity between called and calling party pays models (and the role settlements and levels play in those different models)

3) the ability by centralized procurers of edge access demand to drive access costs down by virtue of purchasing power and value conveyance from the core.

We are missing a big body of academic research around digital network theory and the role of both interconnection out to the edge combined with settlements that clear supply and demand north-south (app to infrastructure) and east-west (between networks, users, providers, etc…). I would be more than glad to help as I did the first real ex ante price elasticity models for digital wireless in 1996 and many of the same precepts hold when applied to all layers and boundaries of the informational stack.

It’s not clear what you mean by “relevant”. It depends on what question you are interested in studying. A controlled experiment on how users respond to pricing would be valid anywhere. Regulators and others are looking at the effects of zero-rating on usage in many countries, not just OECD or European ones.

It’s also not clear what you mean by “overall data consumption”. For one user? For all users? The data we have can help us see how usage of the same apps is affected by non-zero-rated apps. For example, we can see that for certain apps, zero-rating on one carrier results in increased usage on other carriers who do not zero-rate the same apps. I can add certainly commentary and data on the post to that effect. If you’re interested in overall penetration and usage, however, then we obviously can’t answer that, due to the nature of the data sample we can get—we only know about the users who have installed our app.

In any case, you ask good questions and make good points! As I said in the post, we would love more data; we work with what we can get. If you have a way of helping us get the data you’re interested in, we’d appreciate that.

I believe the users, who have subscribed to zero-rating, can access apps that are not free besides the ones which are free. Can you please share data about how usage of non-free apps fared before and after subscription to zero-rating. This will throw light on argument made by supporters of zero-rating, who say that zero-rating improves overall access to the Internet.

That’s a very broad question about a lot of apps, so it’s difficult to answer precisely.

We did see, however, that apps that were zero-rated on one carrier saw increased usage on carriers where the app was not zero rated. The question about how an individual user responds for other apps in response to zero-rating is a good one. That doesn’t really get at the question of penetration which I think the supporters are articulating, but it’s an interesting question nonetheless. Will look into it!

Thanks! Looking forward to reading outcomes of your research. Would have liked to help in data collection in India but zero-rating is now not allowed here.