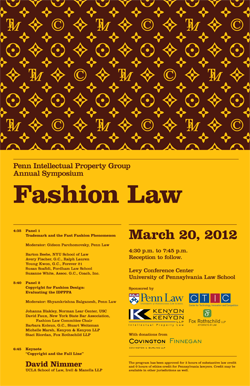

A student group at the University of Pennsylvania Law School has put together a fantastic symposium on the state of fashion law, but along the way they (allegedly) snagged themselves on Louis Vuitton’s trademarks. After creating a poster with a creative parody of the Louis Vuitton logo, they received a Cease & Desist letter from the company’s attorneys claiming:

While every day Louis Vuitton knowingly faces the stark reality of battling and interdicting the proliferation of infringements of the LV Trademarks, I was dismayed to learn that the University of Pennsylvania Law School’s Penn Intellectual Property Group had misappropriated and modified the LV Trademarks and Toile Monogram as the background for its invitation and poster for the March 20, 2012 Annual Symposium on “IP Issues in Fashion Law.”

Ironically, the symposium aims to further education and understanding of the state of intellectual protection in the fashion industry, and to discuss controversial new proposals to expand the scope of protection, such as the proposed bill H.R. 2511, the “Innovative Design Protection and Piracy Prevention Act”.

Ironically, the symposium aims to further education and understanding of the state of intellectual protection in the fashion industry, and to discuss controversial new proposals to expand the scope of protection, such as the proposed bill H.R. 2511, the “Innovative Design Protection and Piracy Prevention Act”.

The attorneys at Penn responded by letter, indicating that Louis Vuitton’s complaint failed any conceivable interpretation of trademark law — outlining the standard claims such as confusion, blurring, or tarnishment — and asserted the obvious defenses provided by law for noncommercial and educational fair use. It indicated that the general counsel had told the students to “make it work” with the unmodified version of the poster, and concluded by inviting Louis Vuitton attorneys to attend the symposium (presumably to learn a bit more about how trademark law actually works.)

I, for one, am offended that the Center for Information Technology Policy here at Princeton has not received any Cease & Desist letters accusing us of “egregious action [that] is not only a serious willful infringement” of fashion trademarks, but “may also may mislead others into thinking that this type of unlawful behavior is somehow ‘legal’ or constitutes ‘fair use’.” You see, our lecture this Thursday at 12:30pm at Princeton by Deven Desai, “An Information Approach to Trademarks”, has a poster that includes portions of registered fashion industry trademarks as well. Attorneys from Christian Dior and Ralph Lauren, we welcome you to attend our event.