Over the last few weeks, I’ve described the chaotic attempts of the State of New Jersey to come up with tamper-indicating seals and a seal use protocol to secure its voting machines.

A seal use protocol can allow the seal user to gain some assurance that the sealed material has not been tampered with. But here is the critical problem with using seals in elections: Who is the seal user that needs this assurance? It is not just election officials: it is the citizenry.

Democratic elections present a uniquely difficult set of problems to be solved by a security protocol. In particular, the ballot box or voting machine contains votes that may throw the government out of office. Therefore, it’s not just the government—that is, election officials—that need evidence that no tampering has occurred, it’s the public and the candidates. The election officials (representing the government) have a conflict of interest; corrupt election officials may hire corrupt seal inspectors, or deliberately hire incompetent inspectors, or deliberately fail to train them. Even if the public officials who run the elections are not at all corrupt, the democratic process requires sufficient transparency that the public (and the losing candidates) can be convinced that the process was fair.

In the late 19th century, after widespread, pervasive, and long-lasting fraud by election officials, democracies such as Australia and the United States implemented election protocols in an attempt to solve this problem. The struggle to achieve fair elections lasted for decades and was hard-fought.

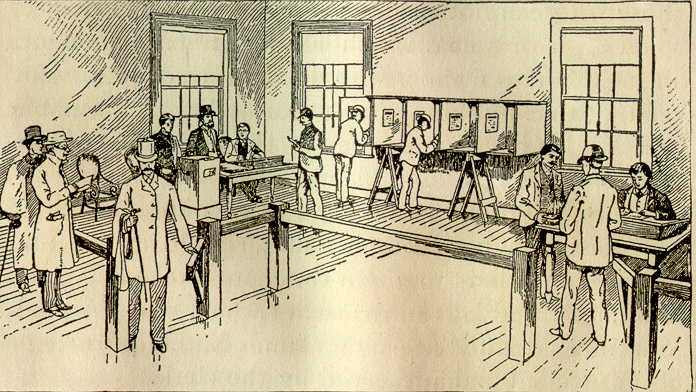

A typical 1890s solution works as follows: At the beginning of election day, in the polling place, the ballot box is opened so that representatives of all political parties can see for themselves that it is empty (and does not contain hidden compartments). Then the ballot box is closed, and voting begins. The witnesses from all parties remain near the ballot box all day, so they can see that no one opens it and no one stuffs it. The box has a mechanism that rings a bell whenever a ballot is inserted, to alert the witnesses. At the close of the polls, the ballot box is opened, and the ballots are counted in the presence of witnesses.

(From Elements of Civil Government by Alexander L. Peterman, 1891)

In principle, then, there is no single person or entity that needs to be trusted: the parties watch each other. And this protocol needs no seals at all!

Democratic elections pose difficult problems not just for security protocols in general, but for seal use protocols in particular. Consider the use of tamper-evident security seals in an election where a ballot box is to be protected by seals while it is transported and stored by election officials out of the sight of witnesses. A good protocol for the use of seals requires that seals be chosen with care and deliberation, and that inspectors have substantial and lengthy training on each kind of seal they are supposed to inspect. Without trained inspectors, it is all too easy for an attacker to remove and replace the seal without likelihood of detection.

Consider an audit or recount of a ballot box, days or weeks after an election. It reappears to the presence of witnesses from the political parties from its custody in the hands of election officials. The tamper evident seals are inspected and removed—but by whom?

If elections are to be conducted by the same principles of transparency established over a century ago, the rationale for the selection of particular security seals must be made transparent to the public, to the candidates, and to the political parties. Witnesses from the parties and from the public must be able to receive training on detection of tampering of those particular seals. There must be (the possibility of) public debate and discussion over the effectiveness of these physical security protocols.

It is not clear that this is practical. To my knowledge, such transparency in seal use protocols has never been attempted.

Bibliographic citation for the research paper behind this whole series of posts:

Security Seals On Voting Machines: A Case Study, by Andrew W. Appel. Accepted for publication, ACM Transactions on Information and System Security (TISSEC), 2011.