(Or, why doing the obvious thing to improve voter throughput in Harris County early voting would exacerbate a serious security vulnerability.)

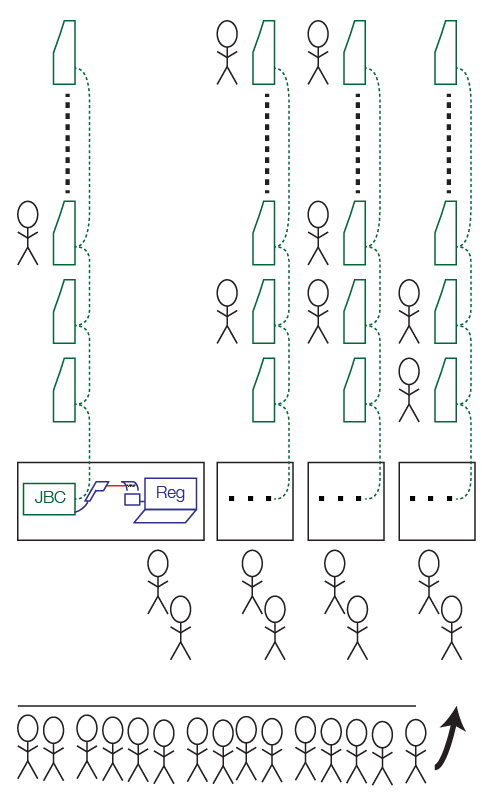

I voted today, using one of the many early voting centers in my county. I waited roughly 35 minutes before reaching a voting machine. Roughly 1/3 of the 40 voting machines at the location were unused while I was watching, so I started thinking about how they could improve their efficiency. If you look at the attached diagram, you’ll see how the polling place is laid out. There are four strings of ten Hart InterCivic eSlate DRE (paperless electronic) voting machines, each connected to a single controller device (JBC) with a local network. These are coded green in the diagram. On the table next to it is a laptop computer, used for verifying voter registration. This has a printer which produces a 2D barcode on a sticker. This is placed on a big sheet of paper, the voter signs it, and then they use the 2D barcode scanner, attached to the JBC, to read the barcode. This is how the JBC knows what ballot style to issue to the voter, avoiding input error on the part of the poll workers. I’ve used the color blue to indicate all of the early voting machinery, not normally present on Election Day (when all of the voters arriving in a given precinct will get the same ballot style).

First, let’s look at this scheme from an efficiency perspective. The main queue has somebody at the end telling you which of the four desks to wait at. I was unlucky and ended up behind somebody who wasn’t actually registered to vote in my county. (They told her, based on her address, that she needs to vote in the adjacent county.) This took a long time. By the time I was checked through, which went quickly, as they only needed to swipe the magstripe on the back of my driver’s license, only one of the ten machines connected to my particular JBC was still in use. All the other machines in my group were idle.

You could improve the efficiency by separating the registration machines, which print the 2D barcodes, from the JBCs, which control the voting machines. To achieve higher utilization, you could add more registration desks and have the voters take those 2D barcodes with them as they go to the JBC that authorizes them to vote. (The JBC prints a 4-digit code on thermal paper. The voter then picks any eSlate and enters that code to get their proper ballot style.)

But what about the security of such a change? The registration computer, its 2D barcode printer, and the 2D barcode scanner are not part of the package that is subject to any Federal or State supervision. We didn’t look at this as part of the California Top-to-Bottom Review for Hart InterCivic equipment. So what’s going on here? The barcode scanner gun appears to be attached to one of the ports on the back of the JBC. Based on what we learned in the California study, the mostly likely thing going on here is that the 2D barcode encodes raw Hart network commands that tell the JBC what to do. This runs afoul of “issue 1” in the report (page 30). This suggests that an adversary could print out a 2D barcode that instructs the JBC (or any connected eSlate) to do a variety of bad things. In the present design, this adversary could work with a corrupt poll worker. If you tried to improve system throughput, as I suggested above, the adversary could be any voter who could substitute a different 2D barcode as they pass from the registration machine to the JBC.

Conclusion: the Hart InterCivic eSlate system, as used for early voting in Harris County, slows down voter throughput whenever there’s a delay at the registration desk. The obvious fixes for this raise unacceptable security risks. Even in its current configuration, it’s unlikely that the system meets the certification requirements of Texas and other states’ laws, due to the uncertified use of the 2D barcode scanner attached to the JBC and its potential use as an attack vector.

Hi,

I couldn’t understand why the change is less secure than the existing system. If you have a corrupt poll worker, he/she could print a malicious code and scan it at the JBC next to him/her. How does separating the registration and the JBC make this more likely?

Thanks.

My strawman efficiency change would reduce the system’s security because it would allow any voter to substitute a pre-printed barcode for the official one, allowing them to inject raw network commands into the system. In effect, the strawman increases the attack surface.

Ah, I get it now. Thank you.

Did you model the two systems as networks of queues and get some results? It would be interesting to see the improvements made.

I didn’t do any sort of formal queuing theory model. My strawman is pretty much the obvious way you’d increase voter throughput — by making enough voter registration tables to keep all the voting machines busy and avoid the case where a single voter going slow through the registration phase causes a stall that leaves voting machines without voters.

It wouldn’t be hard to quantify this. Just sign up as a poll watcher and, with your handy dandy stop watch, time how long it takes voters (average) to get through the registration phase and how long it takes them to vote. You could then sort out how many registration stations per voting machine you need on average to keep things rolling. If you wanted to be clever, as Preston Bannister wrote above, you could “pull people aside” if they’re going to take longer to confirm their registration. (CPU and network designers use phrases like “slow path” and “fast path” to talk about how they handle this sort of thing.)

What one corrupt poll worker could do is likely very, very limited. I hosted and ran the local polling place for several years, in part as a civic responsibility, and in part to see the process from the inside. One of the first rules of security is know who to trust. The polling process is fairly fault tolerant, due to cross checks. As an Inspector my role was to watch the overall process, and one of the things I looked for was poll workers you might be less than honest. (Never happened in about a decade of elections.)

Of course, I was always looking at the process in terms of algorithms. Both in terms of security (there are vulnerabilities, but not so much in my polling place), and in terms of efficiency.

By the 2008 Presidential elections, they had upsized my precinct to double the usual size. (Due to the fact my polling place always ran smoothly.) I had twice the number of poll workers and voting machine (Hart variants). Managed to fit them all in my garage, and have an efficient flow of traffic.

To keep things moving, we usually took the slow-to-process voters to the side, out of the main queue.

Of course, when voting machines in Houston are delivered to schools weeks before the election and left sitting in hallways, one has to question the overall physical security plan for the devices.

Even if you don’t have access to the details of the Hart system, a malicious barcode could easily result in denial of service as people try to figure out what’s wrong.