Summary: Voting machines can be hacked; risk-limiting audits of paper ballots can detect incorrect outcomes, whether from hacked voting machines or programming inaccuracies; recounts of paper ballots can correct those outcomes; but some methods for producing paper ballots are more auditable and recountable than others.

A now-standard principle of computer-counted public elections is, use a voter-verified paper ballot, so that in case the voting machine cheats in counting the votes, the human doing an audit or recount can see the paper that the voter marked. Why would the voting machine cheat? Well, they’re computers, and any computer may have security vulnerabilities that permits an attacker to modify or replace its software. We must presume that any voting machine might, at any time, be under the complete control of an attacker, an election thief.

There are several ways that voter-verified paper ballots can be implemented:

- Voter marks an optical-scan ballot with a pen, deposits into optical-scan voting machine for counting (and for saving in sealed ballot box).

- Voter uses a ballot-marking device (BMD), a computer with touchscreen/audio/sip-and-puff interfaces, which prints an optical-scan ballot, deposits into optical-scan voting machine for counting (and saving).

- Voter uses a DRE+VVPAT voting machine, that is, a Direct-Recording Electronic “touchscreen” machine with a Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trail, which saves the VVPAT printouts in a ballot box.

- Voter uses an “all-in-one” voting machine: inserts blank paper into slot, voter uses touchscreen interface to mark ballot, machine ejects ballot from slot, voter inspects printed ballot, voter reinserts printed ballot into same slot, where it is scanned (or is it?) and deposited into ballot box.

There’s also 1a (hand-marked optical-scan ballots, dropped into a precinct ballot box to be centrally counted instead of counted immediately by a precinct-located scanner), 1b (hand-marked optical-scan ballots, sent by mail) and 2a (BMD-marked optical-scan ballots, centrally counted).

In this article I will put on my “adversarial thinking” hat, and try to design ways that the attacker might try to cheat (and get away with it). You might think that the voter-verified paper ballot will detect cheating, and therefore deter cheating or correct the result–but maybe that depends on which kind of technology is used!

How to cheat with hand-marked optical-scan ballots

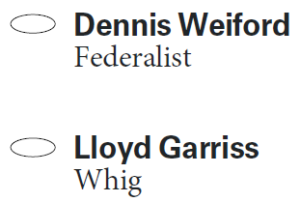

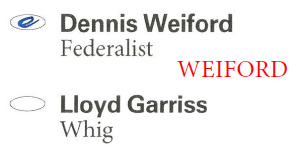

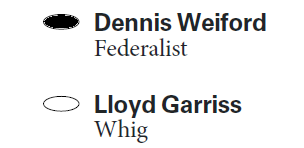

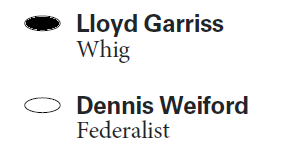

Consider this election between the Federalist party candidate and the Whig party candidate:

How to cheat, method 1: Program the optical-scanner software to shift 20% of the votes from .

What happens during the audit? Because the voter’s original hand-marked choices are marked on the paper ballot, a good risk-limiting audit will detect this (depending on how strong the “risk limit” is), and a recount will correct the count.

What happens during a “digital” audit? Some election directors have proposed to save the time of handling paper ballots during an audit, by just examining the digital images of the paper ballots captured by the high-resolution optical scanners. The problem is that if the optical-scanners are hacked to cheat, then the cheating program can also provide fake high-res digital images. It is essential that audits and recounts be by human inspection of the human-readable portions of the paper ballots.

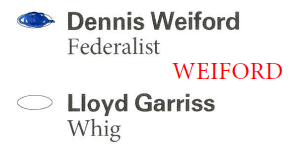

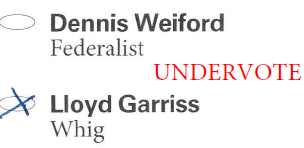

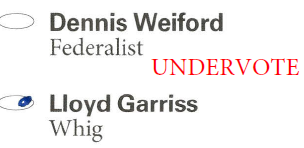

How to cheat, method 2: Program the software to always interpret “marginal” marks in favor of one party. For example, I show in red the hacked machine’s interpretation of these votes:

Whenever there’s an ambiguous vote, it’s interpreted for Weiford if possible, otherwise it’s interpreted as an undervote or overvote. If it’s a close race between the Federalist candidate and the Whig candidate, and the number of imperfectly marked ballots is more than the margin of victory, this cheating will determine the outcome.

What happens during the audit? A good risk-limiting audit will detect that the machine has been “inaccurate,” and will detect an “incorrect outcome” from the machine count. This RLA result should cause a full recount, and the human recount should interpret all the marks consistently. That is, if the state’s rules count row-1,column-2 as a vote for Weiford, then they’ll count row-2,column-2 as a vote for Gariss; or if one is counted as “overvote”, then so will the other.

Will cheating be detected? Maybe not. Although the audit and recount will detect that the machines were “inaccurate,” maybe nobody will notice, or nobody will have strong evidence, that the machines were “inaccurate on purpose.” Thus, the hacker might be foiled in his plan to change the election result, but his hacked software (in favor of the Federalist party) will remain in the voting machine to try another time.

How to cheat with Ballot-Marking Devices

Suppose the voter uses a BMD to print a paper ballot, and then feeds that paper ballot into an optical scanner.

How to cheat, method 3: Mark the wrong votes onto the ballot, and hope the voter doesn’t notice. Don’t cheat twice in the same 10-minute period.

Will cheating be detected? Many voters won’t notice, especially if you confine your cheating to the “downballot” races where the voter may not remember all the names of the people they voted for. If the voter does notice, they’re supposed to alert the pollworker, who will void their misprinted ballot, and allow them to try again. But in that case, how is the pollworker supposed to distinguish between “this voter can’t even remember what he marked onto the ballot” and “the machine cheated, ring the alarm bells?”

What happens during the audit? For those few voters who noticed that their ballot was incorrect, and who marked a fresh ballot, the audit will record their choices correctly. For those voters who didn’t notice that the BMD cheated, the paper ballot, the ballot of record, contains the fraudulent, cheating vote, and it can never be detected or corrected.

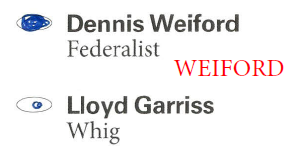

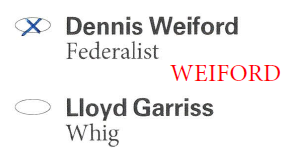

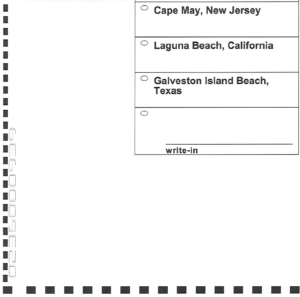

How to cheat, method 4: Take a look at these two BMD-marked ballots — who wins the election?

On the ballot at right, the BMD has cleverly swapped the names as well as the marks. When the optical scanner reads this, both the marks are in the position for Weiford. So Weiford wins 2-0, according to the optical scanner!

What happens during the audit? Human inspection of the human-readable paper ballot will interpret the ballot at right as a vote for Gariss, and the audit will (up to the risk limit) detect the incorrect outcome and call for a recount.

Will cheating be detected? It depends! Probably someone will notice that the ballot at right is in the wrong order. But not necessarily! In some states, the order of candidates is randomized, and different ballot styles will list different candidates first. The machine interpretation of the marks depends on a bar code elsewhere on the ballot. In that case, it would be “normal” that the names are printed in different order.

How to cheat with bar codes

Some  BMDs don’t print an optical-scan form, they print bar codes plus human-readable text. In that case, the optical scanner reads the bar codes, and the human reads the lines of text.

BMDs don’t print an optical-scan form, they print bar codes plus human-readable text. In that case, the optical scanner reads the bar codes, and the human reads the lines of text.

How to cheat, method 5: Print the voter’s selection into the human-readable text, and print the other candidate in the bar code. The voter can’t possibly notice.

What happens during the audit? Human inspection of the human-readable paper ballot will interpret the ballot according the voter’s selection; the audit will (up to the risk limit) detect the incorrect outcome and call for a recount.

What happens during a “digital” audit? Some election directors have proposed to save the time of having actual humans inspect ballots, by scanning the ballots electronically. In such a case, the cheating will not be discovered, because the scanners will see the same fraudulent bar codes they saw the first time. It is essential that audits and recounts be by human inspection of the human-readable portions of the paper ballots.

Will cheating be detected? It depends! A ballot-polling audit will not identify which ballot was incorrectly interpreted. A ballot-comparison audit will identify which ballot was incorrectly interpreted, and will probably be able to detect that fraud (or at least, something seriously wrong) took place.

How to cheat, method 6: Change the vote, both in the bar code and in the human-readable list. The voter might not notice, especially in the downballot races. (Actually, we don’t have good user-study data to test whether the voter will notice. There are some user studies that have tested this question, but only in mock elections where the voter is artificially given a list of candidates to vote for.)

Will cheating be detected? The answer is, even if the voter notices, what happens then? See the analysis of method 3.

What happens during the audit? The fraudulent votes are printed onto the ballot, both in human-readable form and in bar-code form. The audit will not detect the incorrect outcome, and a recount will not correct it.

How to cheat with DRE+VVPAT

I have elsewhere described DRE+VVPAT machines, and explained a bit of how to cheat.

How to cheat, method 7: Print the right votes onto the VVPAT, but record the cheating votes in memory (and the reported vote totals). The voter can’t notice anything wrong.

What happens during the audit? Human inspection of the VVPAT will (up to the risk limit) detect the incorrect outcome and call for a recount. Recount of the VVPAT will get the correct outcome.

How to cheat, method 8: Print the wrong votes onto the VVPAT (and record them in memory, and in the vote count). If the voter notices, proceed as in methods 3 and 6: the voter will void the ballot and try again (but the machine won’t cheat the second time).

How to cheat, method 9: Print the right votes onto the VVPAT-behind-glass, but record the wrong votes in memory (and in the vote count). After the voter presses “OK” to accept the printed VVPAT, print “VOID” onto the VVPAT (as if the voter had detected an error and asked to try again). Then, when the voter isn’t present (in between voters), print a fresh VVPAT with the wrong votes.

Will cheating be detected? No.

What happens during the audit? The fraudulent votes are printed onto the VVPAT and recorded in memory. The audit will not detect the incorrect outcome, and a recount will not correct it.

How to cheat with an all-in-one voting machine

Here and here I described all-in-one machines, that are a combination of BMD + optical scanner, all in a single paper path.

How to cheat, method 5b: Same as method 5.

How to cheat, method 6b: Same as method 6.

How to cheat, method 9b: Actually, this is one way in which an all-in-one machine is more secure than a DRE+VVPAT. The ES&S ExpressVote, or the Dominion IC Evolution, does not have its own paper supply. The voter must insert a blank ballot into the machine, the machine marks that piece of paper. The all-in-one can void a ballot after the last time the voter sees it (that’s very bad!), but it cannot, all on its own, print a fresh ballot because it doesn’t have another sheet of paper handy!

How to cheat, method 10: First, ask the voter whether they want to inspect the printed ballot before depositing it. If the voter says “no”, then print the wrong votes and deposit it in the ballot box. This is described in my previous post.

Will cheating be detected? No.

What happens during the audit? The fraudulent votes are printed onto the paper ballot and recorded in memory. The audit will not detect the incorrect outcome, and a recount will not correct it.

But really, the “permission to cheat” button is such a terrible idea, we might expect most jurisdictions to disable it. So let’s suppose the voter must reinsert the ballot into the slot, after supposedly inspecting it carefully.

How to cheat, method 11: Print some of the voter’s selections onto the ballot, especially the high-profile races such as President, but leave out “state senator” and “county commissioner” and “boondoggle bond issue #3”. Even those alert voters who might notice a vote for a wrong candidate, might not notice that some races are entirely missing. Then, after the voter reinserts the marked ballot into the voting machine, print the cheatin’ choices (not the voter’s selections) in those races.

Will cheating be detected? Perhaps not.

What happens during the audit? The fraudulent votes are printed onto the paper ballot and recorded in memory. The audit will not detect the incorrect outcome, and a recount will not correct it.

Conclusion: what can we learn from all this?

No method is perfect. Any way you mark a paper ballot for optical scan, there’s a way to cheat.

But the attempted cheating on hand-marked optical scan ballots is detected and corrected by risk-limiting audits and recounts.

Many of these ways to cheat cannot be detected by so-called “digital” audits, that is, audits that don’t actually examine, by human inspection, the same pieces of paper that the voters saw. You cannot check whether a computer is cheating, if you’re relying on the computer to tell you what’s on the paper.

the problem with ballot-marking devices and DRE+VVPAT is, even with true audits of the actual paper ballots, some of the ways to cheat cannot be detected in the audit. That is, once the fraudulent votes get onto the paper ballot, once that ballot gets into the ballot box, the fraud can no longer be detected. In any system where the computer marks the votes, we have to rely on the voter to make sure the marks match what they entered on the touch-screen; and

- There’s no evidence that voters are good at that, especially when the on-screen layout looks quite different from the on-paper layout.

- There’s no clear procedure what the voters and pollworkers should do if the fraud is detected. Well, yes, the ballot should be voided and the voter can try again. But this alone will not deter cheating, it just permits the voting machine to cheat again on the next voter who doesn’t look very carefully.

For these reasons, I recommend hand-marked optical scan ballots, and many voting-machine experts agree.

Postscript: Optical scanners that print onto the ballot

In a previous post I explained,

We might wish to allow optical-scanners to print serial numbers onto the ballot, but the optical scanner must not be physically able to print votes onto the ballot. … One solution to this problem is to equip the optical scanner with a printer that is physically able to print only within 1 centimeter of the edge of the paper. As long as no vote-marks are expected at the edge of the paper, then the scanner can print onto the ballot but cannot print votes onto the ballot. Two widely used central-count optical scanners from major voting-machine manufacturers both have this capability: the Dominion ImageCast Central and the ES&S DS850.

The reason for this is to enable efficient ballot comparison audits, which require serial numbers that can link paper ballots to specific cast-vote records.

In a conference call on October 16, 2018 about piloting risk-limiting audits in Rhode Island, Lynn Garland of Maryland was discussing this with the representative of a major voting-machine vendor and with Miguel Nunez, Deputy Director of Elections of Rhode Island. Mr. Nunez showed that the high-speed central-count optical scanner prints these serial numbers on the margin of the ballot, as shown at right. In some ways, that’s a good design: the tiny dot-matrix printer can print only on a 3-millimeter-wide strip of the paper, so it cannot mark votes.

But the serial number is printed in very light ink. Mr. Nunez explained that this makes it difficult to read during a risk-limiting audit. Ms. Garland suggested that the serial number should be printed in some color, such as red ink, that is (1) easily human readable, (2) not sensed by the optical scanner, (3) cannot be interpreted as a vote. The vendor representative seemed quite interested in this proposal and he said he would find out what inks would work. I’ll reserve judgment on this particular suggestion (visible ink not detectable by scanner), but it does show that the design of voting machines for auditability is still evolving, and that major vendors are on board with that concept. I think that’s a good thing.

I proposed a solution to this problem to my Massachusetts State Senator for incorporation into new standards for voting machines.

1) The Voting Machine and the precinct vote tabulator both fill their entire memory with an

Encrypted Signed Tamper Evident Log File [see Bruce Schneier]:

2) The Machine setup and Vote Records are also formatted as a Encrypted Signed Tamper Evident

Log File that overlays the front of the memory filling file, destroying any chance for an attacker to

reproduce the original state of the machine.

3) The Central Tabulator at the Secretary of State’s office randomly issues a challenge to each

voting machine where it must respond with a SHA256 hash of it’s entire memory.

4) If the Challenge Response is incorrect, the voting machine is tampered with and the poll workers

immediately remove the tampered machine from service and check the video tapes for who

might have done the tampering.

5) If the vote file has valid hashes then the votes are intact and can be counted. If the hashes are

incorrect, the votes have been tampered with and are discarded. In either case, the police are

called within minutes of the tampering.

6) 100% of the memory of the voting machine is filled with a known pseudo-random pattern that

cannot be reproduced without the encryption keys that have already been destroyed before

the polling place opens.

7) There no place for an attacker to put malware code in the voting without being detected on the

next challenge.

Variations of Douglas Godfrey’s solution have been proposed before; this paper shows why they don’t work:

On the Difficulty of Validating Voting Machine Software with Software,

by Ryan Gardner, Sujata Garera, and Aviel D. Rubin, Proceedings of the 2nd USENIX/ACCURATE Electronic Voting Technology Workshop, 2007.

https://www.usenix.org/legacy/events/evt07/tech/full_papers/gardner/gardner.pdf

There’s at least one additional way to elude audits. It’s rarely considered, because we’ve been drawn into focusing on outsiders–foreigners, in particular. This method instead deploys insiders.

The concept: Replace the authentic raw documents from the election with a fraudulent set.

This scheme has two basic steps:

1. Make the optical scanner print out whatever vote tallies are desired.

2. Later, provide ballots and ballot images to match the scanner tallies–either by altering the original ballots and images, or by creating an entirely new set.

Is this approach too complex? Do cities have too many ballots for this to work? Is there too great a risk of exposure?

We’d like to reply “Yes!” to all of these. But consider: There are billions of dollars to bestow on the task, and many billions more to reap. So is it reasonable to be concerned about this? If so, how what can we do about it?

The answer requires thoroughgoing checks and balances on our paper ballots.

Hand counting of paper ballots is only a step towards in this direction. After all, unless I’m one of the hand counters, how do I know that none of the hand counts in the precincts in the next state were fraudulent or erroneous? I can only take it on faith. And faith-based election systems are deprecated.

No, the checks and balances we require are ones accessible to the public as a whole, on a “seeing is believing” basis.

The strategy involves 1) entrusting the ballot data to the competing parties in the election, and 2) allowing them to publish their copies of the data.

Step one is to allow each party to create their own images of the paper ballots (for instance, with smartphones). Each party’s set of images then serves as a check and balance on the other sets.

Step two is allow each party to publish its copy. These published copies undergo two levels of checks and balances. First, each party’s published set gets continuously checked and balanced against the party’s offline copy, and gets replaced as soon as any discrepancy is detected. Second, each party’s published set gets continuously checked and balanced against the other parties’ sets, and any deviations either get quickly resolved or get publicized.

This is only a schematic of how we can cope with the risk of insider manipulation. A strategy like this will boost not only “trust” in our election systems, but indeed their “trustworthiness.”

Thanks Andrew for the painstaking roundup of weaknesses of “machine-marked” compared to the much preferable “hand-marked” paper ballots.

I too agree with your conclusion that voter-hand-marked optically scanned paper serves as the best-practice ballot of record. Hand-marked ballots are both our best evidence for the audit, and as a bonus a well designed audit compensates for the occasional misunderstanding inherent in hand-marked paper marked by the broadest distribution of human hands. Of course hand-marked paper that is counted by hand is also acceptable but still needs audit.

To be sure, any effective audit ought to be conducted by hand interpretation of actually voter-verified paper, randomly sampled for efficiency.

It is crucial to watch for the nuances in terminology when it comes to verification and audit of voter intent. For example “verifiable ballots” are different from and may produce less authentic evidence for audit than the “verified ballots” you correctly support here. Hand-marked ballots are almost by definition “verified.”

While paper produced by ballot marking devices may be considered “verifiable,” the same paper ballot may not actually be “verified” by the voter. It might not even be glanced at by the voter even if held in the hand. A well presented request to “verify” on the screen prior to machine-printing a ballot will likely actually distract away from the necessity to verify the eventually printed paper. And hand-marked paper leaves behind better evidence of any voter confusion while machines deliberately leave no record of it.

As you point out there are ways that voters may easily fail to verify what the machine printed even when valiantly attempting to do so. One example you didn’t mention is the likely inability to recognize the meaning of e.g. “Ballot Question 23A YES” when the text of the question is not printed.

Policy makers need to be made aware that both “machine-marked” and “hand-marked” paper might be referred to as “voter marked” in regulations and statutes. Most of the “machine-marked” is probably at best verifiable, but all of the hand-marked is arguably “verified.”

One way the voting system could help convert “verifiable” to “verified” is to ask voters to hand mark a single checkbox at the bottom of a machine-printed paper ballot that attests to having read and verified the printed voter intent. For cases where e.g. blind voters are being assisted by machine, the machine itself will know if the voter has taken the time to verify through audio the marks actually read back from paper.

A deliberate attestation by the voter of verification on paper could substantiate the authenticity of each ballot sampled for the audit as part of a best-practice evidence-based election.

I like the last suggestion, Harvie. LA County is introducing its new Voting Solutions for All People (VSAP) system in 2020. It’s a publicly-owned, disclosed-software ballot marking device that produces a paper ballot that has to be verified by a touchscreen button touch, which then slides the printed ballot back into the machine and into the lockbox behind it. The ballot is Selections Only; I agree with Harvie that this may present difficulties if fraud is practiced by not printing all the selections the voter made; on long California ballots, commissions may easily go unnoticed. However, this new system has many benefits for security and transparency (ballot images created for each ballot when it is centrally scanned; the ballot marking device does not count) that are improvements over our current dotted cards (with no language on them, only numbers and dots, almost impossible for voters to verify that they’ve marked their choices correctly) tabulated by very old software.

Mimi, thanks for your comment. Yes LA is making big improvements from the past. However I have to say that the punch card was not as evil as it was made out to be in 2000. It was a paper ballot with beneficial properties of fail safety, keeping a record of attempts to vote even though the voting devices in Florida at the time were mismanaged in various ways. LA may have been the last US jurisdiction using punch cards.

What concerns me is that LA is also being treated as a prototype of future methods for many states, and as such, it ought to be attentive to the best of designs, practices and principles.

Verified Voting is about to release its renewed Principles for Election Post-election (Tabulation) Auditing. That document will either establish “verifiable” ballots or “verified” ballots as the principle to guide design of voting equipment. One or the other will become the standard for evidence for efficient sampled auditing. I’m hoping the principle is defined by “verified” and the dilution of that principle for practical purposes may be allowed to be “verifiable” but not necessarily verified.

I am not actually familiar with the exact interface to be used for in-person voting in LA. If the user interface to the voting system does not allow the voter to “cast” the paper ballot until the voter indicates they have “verified” what is on the paper (not only what is on screen) and the system cannot print onto the paper after the voter stops looking, then it is in respect to verification close to a best practice. The way to improve further is to have the paper contain the full text and format of a mail ballot rather than “selections-only.”

One way for the voting system to check if verification has taken place would be for the user to input a code that is only printed on the paper to be verified. That would demonstrate that the voter at least read what was on the paper.