In a time when U.S. tech employees are organizing against corporate-military collaborations on AI, how can the ethics and incentives of military, corporate, and academic research be more closely aligned on AI and lethal autonomous weapons?

Speaking today at CITP was Captain Sharif Calfee, a U.S. Naval Officer who serves as a surface warfare officer. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and U.S. Naval Postgraduate School and a current MPP student at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Afloat, Sharif most recently served as the commanding officer, USS McCAMPBELL (DDG 85), an Aegis guided missile destroyer. Ashore, Sharif was most recently selected for the Federal Executive Fellowship program and served as the U.S. Navy fellow to the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments (CSBA), a non-partisan, national security policy analysis think-tank in Washington, D.C..

Sharif spoke to CITP today with some of his own views (not speaking for the U.S. government) about how research and defense can more closely collaborate on AI.

Over the last two years, Sharif has been working on ways for the Navy to accelerate AI and adopt commercial systems to get more unmanned systems into the fleet. Toward this goal, he recently interviewed 160 people at 50 organizations. His talk today is based on that research.

Sharif next tells us about a rift between the U.S. government and companies/academia in AI. This rift is a symptom, he tells us, of a growing “civil-military divide” in the US. In previous generations, big tech companies have worked closely with the U.S. military, and a majority of elected representatives in Congress had prior military experience. That’s no longer true. As there’s a bifurcation in the experiences of Americans who serve in the military versus those who have. This lack of familiarity, he says, complicates moments when companies and academics discuss the potential of working with and for the U.S. military.

Next, Sharif says that conversations about tech ethics in the technology industry are creating a conflict that making it difficult for the U.S. military to work with them. He tells us about Project Maven, a project that Google and the Department of Defense worked on together to analyze drone footage using AI. Their purpose was to reduce the number of casualties to civilians who are not considered battlefield combatants. This project, which wasn’t secret, burst into public awareness after a New York Times article and a letter from over three thousand employees. Google declined to renew the DOD contract and update their motto.

U.S. Predator Drone (via Wikimedia Commons)

On the heels of their project Maven decision, Google also faced criticism for working with the Chinese government to provide services in China in ways that enabled certain kinds of censorship. Suddenly, Google found themselves answering questions about why they were collaborating with China on AI and not with the U.S. military.

How do we resolve this impasse in collaboration?

- The defense acquisition process is hard for small, nimble companies to engage in

- Defense contracts are too slow, too expensive, too bureaucratic, and not profitable

- Companies aren’t not necessarily interested in the same type of R&D products as the DOD wants

- National security partnerships with gov’t might affect opportunities in other international markets.

- The Cold War is “ancient history” for the current generation

- Global, international corporations don’t want to take sides on conflicts

- Companies and employees seek to create good. Government R&D may conflict with that ethos

Academics also have reasons not to work for the government:

- Worried about how their R&D will be utilized

- Schools of faculty may philoisophically disagree with the government

- Universities are incubators of international talent, and government R&D could be divisive, not inclusive

- Government R&D is sometimes kept secret, which hurts academic careers

Faced with this, according to Sharif, the U.S. government is sometimes baffled by people’s ideological concerns. Many in the government remember the Cold War and knew people who lived and fought in World War Two. They can sometimes be resentful about a cold shoulder from academics and companies, especially since the military funded the foundational work in computer science and AI.

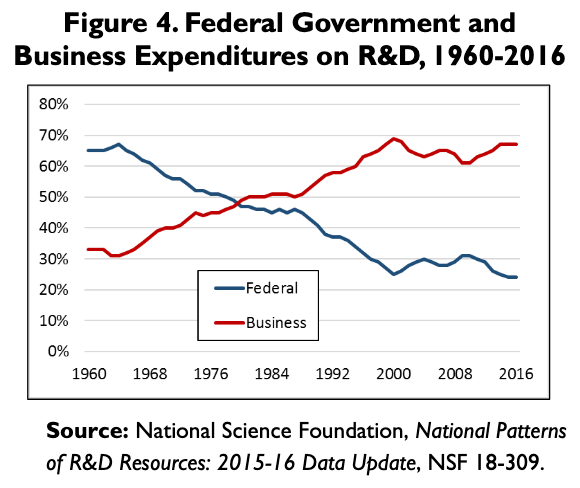

Sharif tells us that R&D reached an inflection point in the 1990s. During the Cold War, new technologies were developed through defense funding (the internet, GPS, nuclear technology) and then they reached industry. Now the reverse happens. Now technologies like AI are being developed by the commercial sector and reaching government. That flow is not very nimble. DOD acquisition systems are designed for projects that take 91 months to complete (like a new airplane), while companies adopt AI technologies in 6-9 months (see this report by the Congressional Research Service).

Conversations about policy and law also constrain the U.S. government from developing and adopting lethal autonomous weapons systems, says Sharif. Even as we have important questions about the ethical risks of AI, Sharif tells us that other governments don’t have the same restrictions. He asks us to imagine what would have happened if nuclear weapons weren’t developed first by the U.S..

How can divides between the U.S. government and companies/academia be bridged? Sharif suggests:

- The U.S. government must substantially increase R&D funding to help regain influence

- Establish a prestigious DOD/Government R&D one-year fellowship program with top notch STEM grads prior to joining the commercial sector

- Expand on the Defense Innovation Unit

- Elevate the Defense Innovation Board in prominence and expand the project to create conversations that bridge between ideological divides. Organize conversations at high levels and middle management levels to accelerate this familiarization.

- Increase DARPA and other collaborations with commercial and academic sectors

- Establish joint DOD and Commercial Sector exchange programs

- Expand the number of DOD research fellows and scientists present on university campuses in fellowship programs

- Continue to reform DOD acquisition processes to streamline for sectors like AI

Sharif has also recommended to the U.S. Navy that they create an Autonomy Project Office to enable the Navy to better leverage R&D. The U.S. Navy has used structures like this for previous technology transformations on nuclear propulsion, the Polaris submarine missiles, naval aviation, and the Aegis combat system.

At the end of the day, says Sharif, what happens in a conflict where the U.S. does not have the technological overmatch and is overmatched by someone else? What are the real life consequences? That’s what’s at stake in collaborations between researchers, companies, and the U.S. department of defense.

An under-emphasized issue is that the big tech companies, even those headquartered in the U.S., are global in nature.

And it’s not just that working with the U.S. military may cut off commercial opportunities to work with other governments. It’s also about the people inside the companies. The engineers, even those that reside and work in the U.S., come from all over the world. Many of them would never be able to get the clearance needed to work on military projects because of where they are from or because they’re not yet U.S. citizens. Some have lived in war zones and perhaps even been targeted by the U.S. military. Big tech’s most important asset is the people who work for them. They can’t afford to lose people because they chose a side, regardless of which side they choose.

Big Tech’s bread and butter is their users, who also happen to live all over the globe. Some incremental money from a couple of government contracts seems unlikely to offset the cost of losing a slice of their user base because they chose a side.

This post leaves me disappointed and very concerned. The author has been sucked in to a downward vortex of military/industrial/cyber FUD where ethics and morals are put aside to be in awe of self-aggrandizing militarism. Thank those who stand against ” lethal autonomous weapons”. Thank all who question the obscene expense, waste, inhuman death and destruction when commercial and military forces shake hands for money and power.

I hope there were some in the CITP audience who have learned from our 20th century history and pushed back questioning Captain Sharif Calfee. Mr Matias does not document anyone speaking up. Sadder still because nearly every paragraph of the post has much to be unpacked and discussed.

Hi Bernhard, thanks for your thoughtful, valuable comment. When I liveblog talks by others, I don’t report my personal opinions. As a pacifist who continues to make numerous public statements against the use of autonomous lethal weapons and as someone who has encouraged internal activism by tech employees, I was interested to hear more about the impact of tech employee activism on U.S. military R&D.

I can also say that there were several questions after the talk that questioned Sharif’s talk, but I did not have time to record the Q&A this time.

“Establish a prestigious DOD/Government R&D one-year fellowship program with top notch STEM grads prior to joining the commercial sector”

I guess if loss of innocence is your goal, can’t do better than that.

I agree – under today’s US /Military tech programs we need to be above and beyond those systems that are already being compromised. Those is sensitive positions of government and in the military need protection from invader’s that seem destined to disrupt our AI systems.

Yet is seems we must continue on securing world peace rather than looking for ways to end all mankind. Defense yes – offense at a last resort.

The world today has enough problems without taking out all the people who live on this planet. Radicals need to be eliminated by their governments in each society world wide.

We are treading on very thin ice the last few years . The world’s survival as a whole (and to that I mean “all peoples” on this planet) need to realize that the next war will leave far less avenues of survival.

It seems we have more radical movement in motion. The US can’t do it alone. The UN and NATO in all high level positions have to realize that the next war will result in near total devastation of this planet and its peoples.

How and why they can’t see that is beyond me.

Add to this our issues regarding Climate Change – we seem to overlook that this is the only planet we have to live on and we are destroying our environment.

So one or the other “nuclear war” and/or “climate change” will be our shortcomings. And we call ourselves human beings. We seem to destroy everything sooner or later in the name of progress. I’m really surprised we made it this long.

What a world we leave our Kids and Grand-Kids who have to live with what we made of our world. Great legacy to leave isn’t it.