By Colleen Josephson and Yan Shvartzshnaider

The concerning trend of tracking of user’s location through their mobile phones has very serious privacy implications. For many of us, phones have become an integral part of our daily routine. We don’t leave our homes without and take them everywhere we go. It has become alarmingly easy for services and apps to collect our location and send them to third-parties while the user is unaware. Location tracking generally works poorly indoors. Tracking services can infer your general location up to a building using current technologies like GPS, WiFi, cellular triangulation. However, your movements inside can’t be precisely tracked. This level of obfuscation is about to disappear as a new radio technology called ultra-wideband communications (UWB) becomes mainstream.

In its recent iPhone launch, Apple introduced the U1 ultra-wideband chip in the iPhone 11. Ultra-wideband communications use channels that have a bandwidth of 500Mhz or more, with transmissions at a low power. In this blog post, we would like to give a brief introduction into the technology behind the chip, how it operates and discuss some of its promises as well as implications for our day-to-day activities.

Why would users want ultra-wideband? On the iPhone 11 Pro product page, Apple says, “The new Apple‑designed U1 chip uses Ultra Wideband technology for spatial awareness — allowing iPhone 11 Pro to understand its precise location relative to other nearby U1‑equipped Apple devices. It’s like adding another sense to iPhone, and it’s going to lead to amazing new capabilities”. For now, the features available to the U1 chip are restricted to “[pointing] your iPhone toward someone else’s, and AirDrop will prioritize that device so you can share files faster”.

However, as the number of devices equipped with a UWB chip grows, it will enable a broad spectrum of applications. UWB is not a new technology, but we are seeing a renewed interest due to vastly improved operational distance. Over the years, researchers have developed a variety of UWB applications such as estimating room occupancy, landslide detection, and human body position/motion tracking. Perhaps the leading use case for UWB technology has been precise indoor localization, with accuracies between 10-0.5cm. Indoor localization is the process of finding the coordinates of a target (i.e. a phone) relative to one or more fixed-point anchors that also contain UWB radios. The relative coordinates are then mapped to a reference (e.g. blueprints) to provide an absolute location. High-accuracy localization is especially useful in contexts where traditional GPS is not accurate enough, or cannot reach. A number of other technologies have been explored for indoor localization, such as WiFi and Bluetooth, but the accuracy of these techniques is on the order of meters1, not centimeters.

The key to enabling centimeter-level localization is the wide bandwidth of UWB. Transmissions that occupy a broad bandwidth are short in duration and known as pulses or impulses. These short duration impulses allow accurate measurement of time of flight (ToF): the time it takes for a signal to propagate from point A to point B. Radio frequency (RF) waves travelling through air have a velocity that is very close to the speed of light. This means that if we can accurately measure time of flight, then we know the distance between A and B. Similar to how bats use echolocation to sense their environment, UWB pulses can be used to sense distances between two transmitters. The shorter the duration of the impulse, the more precise the distance measurement will be. There are a few different ways to use this information for localization/positioning, but the most common for navigation is time difference of arrival. This system relies on having three or more anchors that are also equipped with UWB chips. The anchors have synchronized clocks. To calculate the position of the phone, the anchors forward their ToF measurements to a central service that knows the absolute location of the anchors (e.g. mapped onto blueprints) and calculates where the phone is located relative to the anchors.

For now indoor localization is not common, since most buildings do not have an UWB anchor infrastructure. However, in October 2019 it was announced that Cisco is teaming up with Czech company Sewio to integrate UWB chips in wireless access points. This is a major step towards enabling ubiquitous indoor localization, as it will make it much more likely that any building with WiFi can also support indoor localization. The new Cisco access points will support IEEE 802.15.4z, an ultra-wideband communications standard that was designed by the UWB Alliance, an organization that receives input from members like Apple, Decawave, Samsung and Huawei. Apple’s U1 chip adheres to the same standard, so the U1 and the Cisco access points will be able to communicate. If an Apple U1 chip responds to ranging exchanges initiated by the Cisco access points, then it is a simple matter of the owner of the network running a location calculation service to obtain the Apple U1 chip’s position.

What makes the current generation of UWB chips stand out is that for the first time they will be deployed in mobile phones, which for a lot of people is an inseparable part of their daily routine. While it is promoted by Apple as just another sensor to “Share. Find. Play. More precisely than ever,“ this technology has the power to disrupt existing societal norms. Suddenly businesses will be able to track an individual’s location within their stores down to the centimeter, which gives them the power to track which products you look at in real-time. Similar to the debated facial recognition technology, UWB localization offers a new capability to capture and ultimately profile identities of a user. Essentially, the new chip is a marketer’s dream in a box. Shops already track your purchases, leading to cases like the infamous 2012 case where Target unintentionally divulged a teen’s pregnancy to her father. When a store has UWB-enabled access points, it will be easy to monitor a phone’s location indoors and track what you considered purchasing in addition to what you actually purchase. Even without UWB, Cisco already has a feature that lets stores track your presence via phone WiFi, “to engage users and optimize marketing strategies”.

This WiFi tracking is possible even if your device is not associated with the network, because devices with the WiFi chip enabled periodically send out probe packets to discover which networks are available. A similar technique could be used with UWB to enable even more precise tracking throughout the store. This means that your location information could be used even if location permissions are closely monitored for apps on the phone. The Cisco/Sewio announcement off the bat mentions a “location-based marketing in retail” as a potential use case. In a mall-wide network setup, the routers could retain information that will enable inferring your movements in other stores as well. Essentially, offering a physical world analogy to web tracking. Companies like Five Tier, JCDecaux and other use existing location tracking technologies to display ads to the users in the vicinity on nearby screens, even billboards. Current WiFi-based phone tracking lets retailers monitor which store you are in, but with UWB, companies will be able to monitor which products you are looking at. This information could be used to push targeted ads that could follow you both physically and online. Imagine going to browse for jewelry, and then seeing billboards for diamonds follow you as you drive home, and have that continue on your web browser and smart TV once you get home.

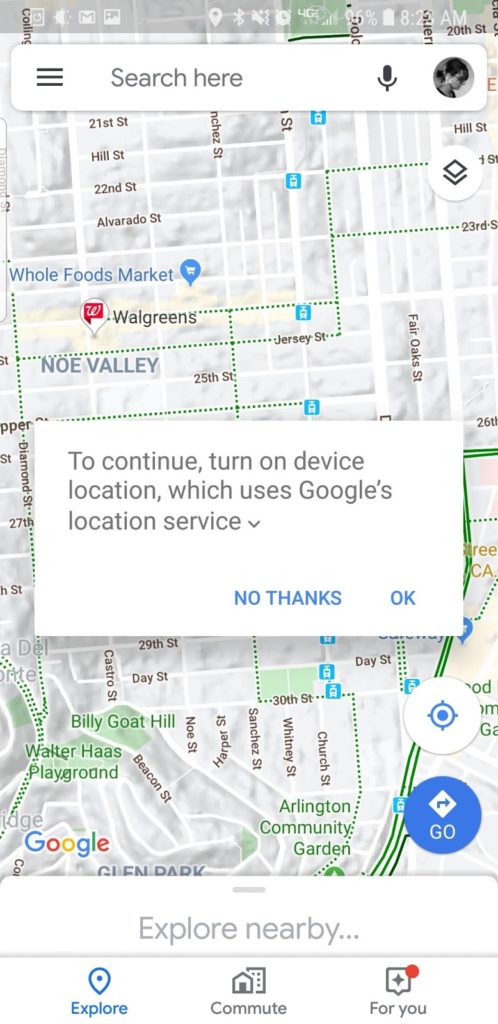

Historically companies have opted to chase the marketing dream instead of respecting users’ privacy. Companies like Google and Facebook argue that they provide users with adequate privacy controls, but privacy researchers disagree. Furthermore, privacy choices are often eroded either by bugs or misleading requests. One recent incident report by Brian Kreb, details how Apple continues to collect location information, despite location-based system services being disabled. According to Brian, Apple’s response stated, “this behavior is tied to the inclusion of a new short-range technology that lets iPhone 11 users share files locally with other nearby phones that support this feature, and that a future version of its mobile operating system will allow users to disable it”. And even if location services are reduced or disabled, some apps constantly try to get users to turn these services back on. As Figure 3 shows, some messages are deceptive, causing users to believe that the app won’t work without re-enabling high-accuracy (WiFi-assisted) location. And even if the apps using location data are trustworthy, choosing to leave high precision location services enabled can still allow stores with UWB infrastructure to closely track you without your explicit consent by using one-way ranging with probe packets2 (see 7.1.1.2 in Application of IEEE Std 802.15.4).

Figure 3: Some mobile phone apps repeatedly encourage users to turn on location permissions that are not actually necessary.

UWB technology could disrupt our preconceived privacy expectations about how our location data is shared and used. In a recent empirical study Martin, Kirsten E., and Helen Nissenbaum show that “that tracking an individual’s place – home, work, shopping – is seen to violate privacy expectations, even without directly collecting GPS data, that is, standard markers representing location in technical systems.”

It can also offer potential benefits to the consumer. For example, we can envision an UWB localization service that helps you find a specific store inside a large mall, navigate underground tunnel systems such as those featured in the cities of Montreal and Seoul, or helps you navigate to the precise location of where an item is located in a store. Nevertheless, given the current state of privacy policies, confusing controls, and with the current privacy regulations being poorly equipped to address the potential violation of users’ privacy expectations in public places, without proper oversight, there is a significant risk in these types of technologies being misused for nefarious purposes such tracking and surveillance. As these technologies become pervasive, it becomes vital to fully consider the implications of these techniques on our way of life, specifically the effect they have on the established societal norms and expectations.

In this blog post we outlined what UWB is and how it can be used to track location with unprecedented accuracy. While accurate location tracking could be useful, users often find that their data is used in unexpected ways that requires close reading of dense legal agreements. This flow of information is legal, but still violates users’ privacy expectations. These expectations are even more deeply violated when a phone’s location can be tracked despite carefully selected privacy settings on the device. Although this level of ubiquitous centimeter-level tracking is not yet a reality, the pieces are rapidly falling in place. Now is the time to act, before the norms of privacy erode further. Regulators, businesses and end-users need to work together to design a system that can benefit both businesses and customers without unexpected consequences for the customers.

We would like to thank Helen Nissenbaum for providing feedback on the early drafts.

Interesting article, I had no idea about UWB localization, however for a while now I have been wondering about the new mobile wireless spectrum 5G (millimeter wave). As millimeter wave provides a resolution from cm to mm, combined with it’s history of use as a radar band, would seem to offer another avenue to localizing people and devices. One that will likely be more mandatory than UWB as older data transmission technologies begin to be retired. Similar, but less accurate, results on localization and even body tracking have been achieved with the comparatively large but similar wifi frequencies, using routers as anchors and antennae arrays. That being the case, the smaller wavelength of 5G might offer results that are competitive with UWB. Though admittedly I’m not very educated so I may be misunderstanding the technology involved. In any case, thanks for bringing this to the public’s attention.