Why did New Jersey counties keep choosing one insecure voting machine after another, for decades? Only this year did I realize what the reason might be.

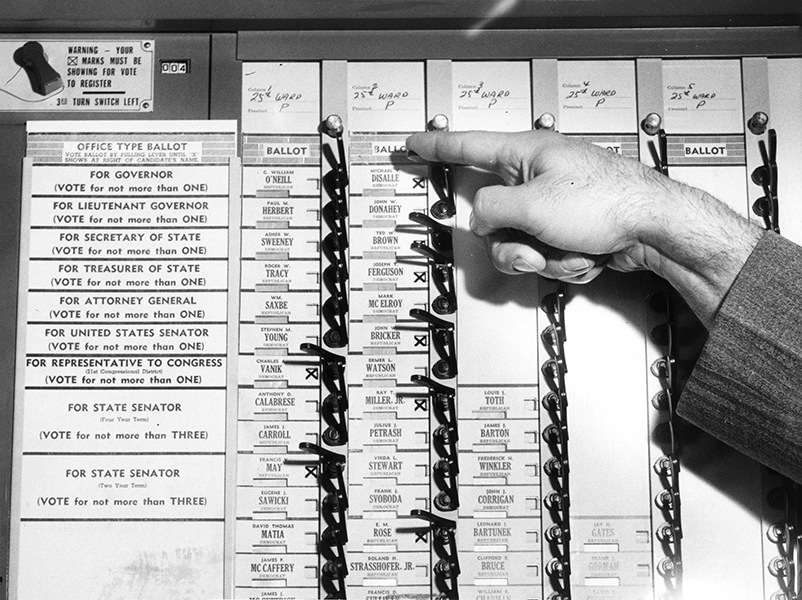

A century ago, New Jersey (like many other states) adopted lever voting machines that listed the offices by row, with the parties (and their candidates) across the columns:

The Help America Vote act of 2002 banned the use of those machines (and also banned punch-card voting machines). The states that were using paper ballots could continue to use them, but the states and counties using lever machines or punch cards had to switch to something else: either paper ballots (counted by optical scanners) or paperless touch-screen voting machines. Election-security experts urged the states and counties to avoid touch-screen voting computers, but almost every New Jersey county ignored them and adopted the AVC Advantage voting machine:

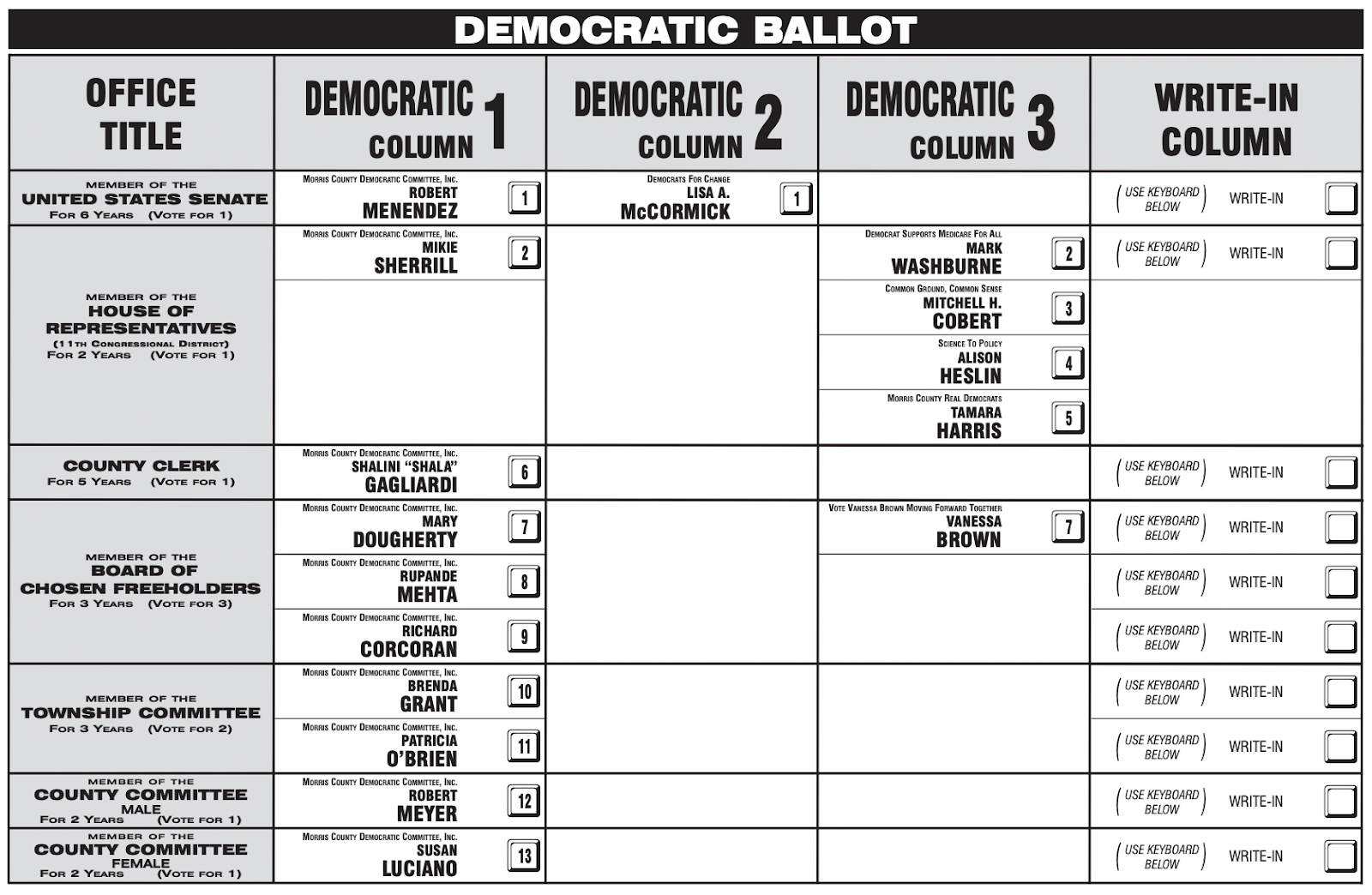

This voting machine, like the lever machines it replaced, has the offices down the rows and the parties or candidates across each row. Here’s an example of a primary election on the AVC Advantage, with one row for each office and the candidates listed across each row. Both the Democratic ballot and the Republican ballot are shown, but each voter would be enabled to vote in only one of those primaries, depending on their party registration.

Between 2001 and 2007, many states (including New Jersey) adopted touchscreen voting computers, but most of them soon realized that it’s a mistake to use machines with no paper trail—because if those machines are hacked, they can report whatever vote totals the hacker wants, and there are no paper ballots to recount. Between 2008 and 2012, almost every state that had (unwisely) adopted touchscreen voting machines, (wisely) switched over to optical-scan paper ballots.

But not New Jersey. Finally in about 2018 the counties realized that they really had to switch to voting machines with a paper trail. Computer security experts again urged New Jersey counties to adopt hand-marked optical-scan paper ballots, but most counties insisted on using a full-face touchscreen machine: the ExpressVote XL.

This machine has rows and columns, just like the Shoup lever machines from a century ago, just like the AVC Advantage from a quarter century ago. Unlike the AVC, the ExpressVote XL does have a kind of paper trail, but it’s the worst possible, most insecure kind of paper trail. The whole purpose of a paper trail is that, in case the voting machines are hacked to make them cheat, you can recount the paper ballots that the voters actually marked or verified. When the voters fill in ovals with a pen, you can be pretty sure that the voters made the choice, not the pen! But the ExpressVote paper “summary card” is printed by the computer (after the voter makes selections on the touchscreen), and displayed in a little window to the right of the screen. Most voters don’t pay much attention to that window; the text is small and can be hard to read behind the glass, and worst of all, the votes are encoded on the paper in barcodes that are impossible for the voters to verify.

The ExpressVote XL is much more expensive to use. An optical-scan polling place needs one $5,000 optical scanner and ten 25-cent pens; an ExpressVote polling place needs two or more $12,000 touchscreens. Polling places with ExpressVotes can experience long lines of voters waiting their turns to use the machines, while jurisdictions with hand-marked paper ballots can just buy more pens and let many voters mark their ballots simultaneously. The ExpressVote XL is less secure than hand-marked paper ballots: voters can’t verify barcode votes, and even though there is also human-readable text, studies have shown that most voters don’t review that carefully. And the ExpressVote is prone to screwups: even when it’s not hacked on purpose, sometimes it prints the wrong votes in the human-readable part of the paper.

Each New Jersey county Board of Commissioners, an elected body, decides which kind of voting machines to buy, choosing from a list approved by the Secretary of State. Why did so many counties choose this machine, even though it’s much more expensive and much less secure?

I must admit, I didn’t fully understand the answer to that question until 2024, when the lawsuit Kim v. Hanlon was argued and decided in New Jersey Superior Court. Andy Kim, a candidate in the Democratic primary for U.S. Senate, sued all the county clerks in New Jersey. He argued that NJ primary ballot layouts unconstitutionally put a “thumb on the scale” in favor of the candidates favored by each county’s political party machine, by grouping the machine-favored candidates together in the first column (called the “county line”), and putting the disfavored candidates far off to the right, in “Ballot Siberia”.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit provided an expert analysis of the thumb on the scale, showing what a huge advantage this gives to the candidates in the first column.

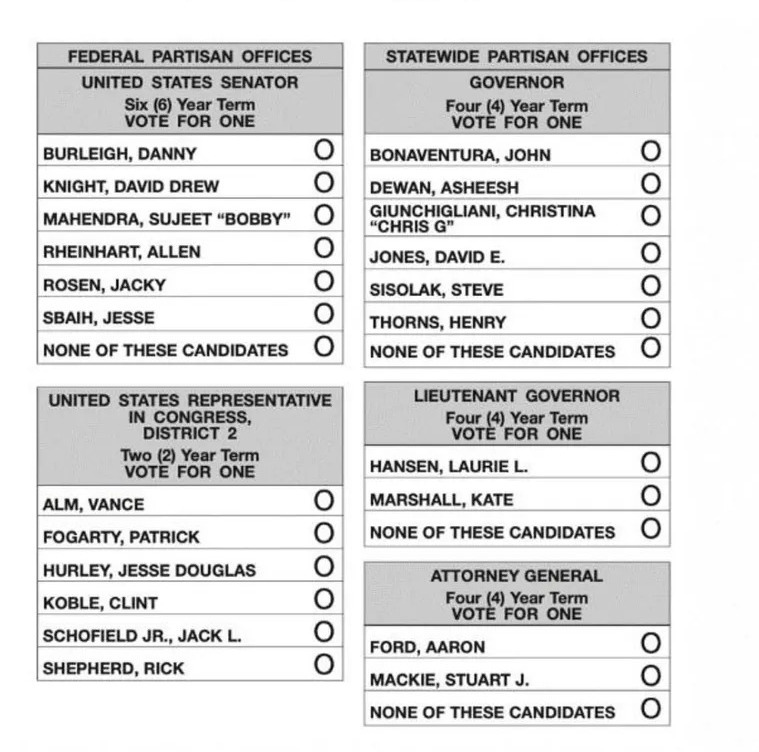

In contrast, almost all other states use an “office block” ballot format, in which each contest is in its own block, and there’s no line-up of “party endorsed” candidates:

The judge ruled that the county line “thumb on the scale” is illegal, and in March 2024 ordered New Jersey counties to use an office-block layout in the June primary election. (Fortunately, the ExpressVote XL doesn’t require county lines, and can be configured to office-block ballots.)

But how and why did New Jersey counties decide in 2002 to use the AVC Advantage, and in 2019 to use the ExpressVote XL? For over 20 years I’ve been studying voting machine security, voting-machine design, election procedures, and New Jersey elections. I had been mystified why New Jersey county commissions clung so tightly to their rows-and-columns voting machines, when those machines are much more expensive and much less secure. It wasn’t until the Kim v. Hanlon lawsuit that I finally understood the picture.

The County Commissioners who decide on voting machines are elected officials, Democrat and Republican, who are generally members of their county political organizations and endorsed by those political machines. The members of County Boards of Elections, that make recommendations to the County Commissions, are selected by the political parties. The “county line” helps county political bosses gain influence over elected officials, because those officials don’t want to be in “Ballot Siberia” in their next elections.

The ExpressVote XL, with its large 32-inch screen, facilitates a rows-and-columns ballot layout. The rows-and-columns layout allows a “county line,” where the party-machine-endorsed candidates are in favored position and the outsider candidates are in Ballot Siberia. Maybe that’s the reason that New Jersey counties fought so hard to keep using full-face touchscreen voting machines, 22 years ago when they chose to purchase the AVC Advantage and 5 years ago when they chose the ExpressVote XL. To preserve that thumb on the scale, they were willing to spend much more money on less secure voting machines.

By the way, I’m not against the concept of county political-party organizations: Republican, Democratic, Libertarian, Green, Working People’s Party, whatever. Americans have a right of free association, and political parties can serve a very useful role in helping Americans make their voices count at the polling place. But if we’re going to have primary elections, there probably shouldn’t be a thumb on the scale.

Note: I testified as an expert witness in Kim v. Hanlon. But my testimony was not about whether rows-and-columns was good or bad, it was not about the thumb on the scale. My testimony was just that the voting machines in New Jersey could be used with ballot layouts other than rows-and-columns, such as the “office block” format used in almost every other state.

Back in 1934, Joseph P, Harris wrote: “”There has been a great deal of controversy in this country over the merits of the Massachusetts or office group ballot, versus the Indiana or party column ballot. A majority of the states now use the party column ballot. The political organizations have always fought very bitterly any movement to do away with the party column ballot, with the familiar roosters, elephants, or other party emblems at the top of the party column, while independents and reformers have sought to secure the true Australian or Massachusetts type of ballot.” (Election Administration in the United States, The Brookings Institution, 1934, page 36, bottom.)

Harris was mostly concerned with straight party voting, something greatly simplified by use of the party column (or party row ballot, if the roles of rows and columns are exchanged, as they sometimes are), but it is worth noting that straight-party voting on office-block ballots is entirely feasible and all modern ballot tabulators support it as an option.

I had assumed that the eastern states like New York and New Jersey were using party column ballots because they were written into state law.

Harris also recommends that “the names of candidates should be rotated on the ballot to the extent necessary that each candidate may share equally with other candidates for the same office, each position on the ballot.” (Election Administration, page 39, top.) Rotation on party column (or party row) ballots is generally done by rotating the order of parties differently in different precincts. In states that have office block ballots, rotation can be done with far greater flexibility. I recently looked at the rotation rules in Kansas, and I cannot see how to conform to Kansas rules on a party column ballot. (Kansas Statutes 25-212.)

It’s clear that New Jersey needs a rotation rule! As Joseph Harris’s discussion from the 1930s make very clear, this has been a recognized best practice for a long long time.