Colorado has become the first state mandating transparency specifically around platform fees and driver wages from rideshare platforms like Uber and Lyft, whose opaque AI and algorithmic operations have historically evaded legal oversight. On June 5 2024, Governor Jared Polis signed SB24-075, the Transportation Network Company Transparency bill into an act, compelling these platforms to reveal their take rates – how rider prices are split between the platform and drivers. Additionally, it requires upfront disclosure to drivers of ride destinations, expected compensation before acceptance, and semi annual data disclosures to the state. Addressing long-standing concerns over arbitrary deactivations, the law also certifies an official “driver support organization” to assist impacted workers.

Our team, the Workers Algorithm Observatory, at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) alongside our community partners Towards Justice and Colorado Fiscal Institute, influenced negotiations and actual bill language shaping this pioneering legislation drawing on our recent research, which uncovered how rideshare platforms’ lack of transparency can result in worker harms. Furthermore, building on these findings and extending beyond, we collaborated with CITP’s Tech Policy Clinic to release a policy memo advocating for mandatory public data disclosures through standardized rideshare transparency reports from rideshare platforms to foster accountability and enhance worker well-being across all states.

So, what’s really going on behind the scenes?

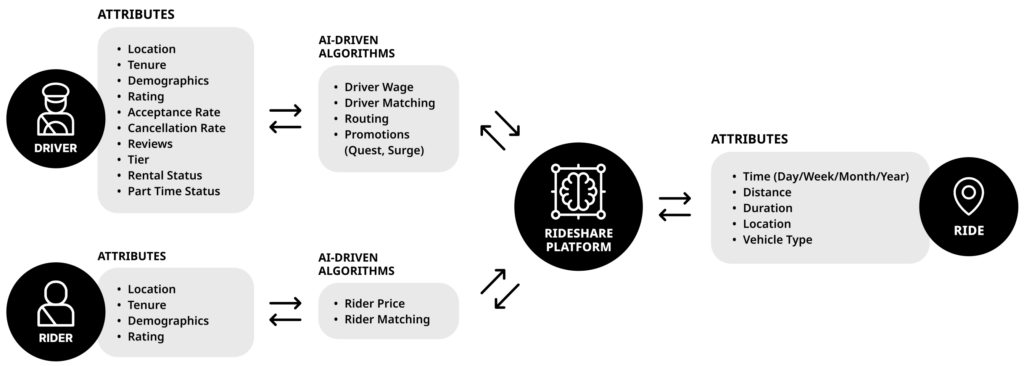

Rideshare platforms rely on opaque algorithms to make decisions about everything from assigning rides, setting prices, to even deactivating drivers from the platform. Unfortunately, neither drivers nor riders understand how these decisions are made. Our analysis of over a million comments from online driver forums and interviews with drivers showed that this transparency gap and information asymmetry is a major source of frustration and uncertainty.

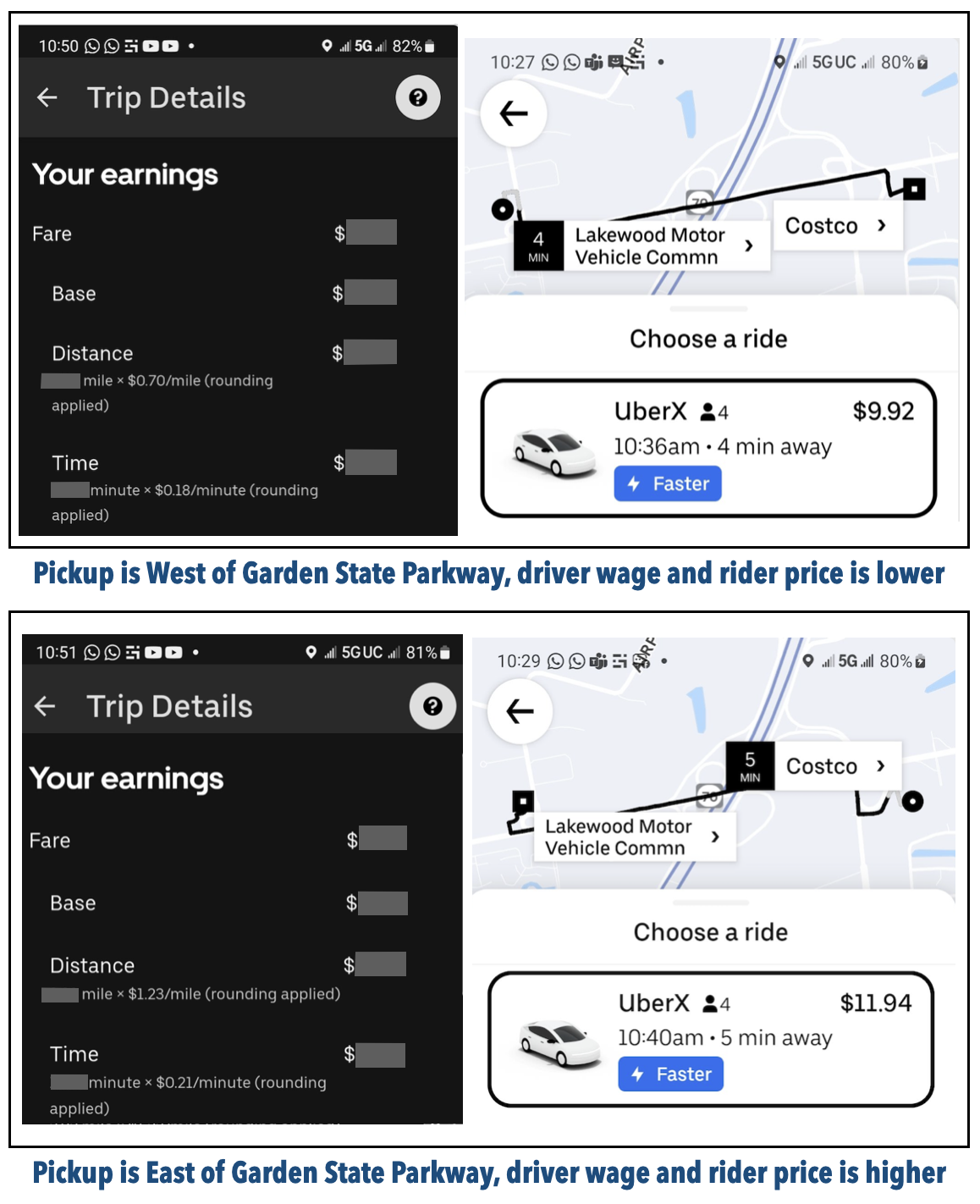

Drivers are in the dark about why they’re offered certain promotions, how fares are calculated, where they’re actually going, or even how they’re assigned specific rides. This “soft control” often manipulates worker behavior through gamification and makes it nearly impossible for them to plan their work or establish stable routines. It also enables algorithmic wage discrimination under the guise of dynamic pricing, where workers can earn vastly different wages for similar work based on individual data. Dynamic wages aren’t inherently illegal and are common in traditional employment, unless based on protected characteristics or falling below minimum wage. However, rideshare differs in four key aspects: (i) lack of transparency, (ii) absence of recourse, (iii) high unpredictability, and (iv) shirking the “equal pay for equal work” principle. Unlike traditional employers who must justify pay differences, rideshare platforms avoid this responsibility. For drivers relying on rideshare as primary income, these unpredictable, dynamic wages can result in physical, financial and emotional harms.

Riders aren’t faring much better. As a rider, have you ever wondered why your fare changes so drastically at different times of day, or why your friend paid a different price for a similar ride? Without transparency, it’s hard to know if riders are facing algorithmic price discrimination. Dynamic prices exist in other industries like grocery stores or airlines and aren’t inherently illegal, but consumers typically understand the pricing rules merchants set. For example, shoppers might pay more for groceries at Whole Foods than at Aldi, justifying the premium with perceived benefits like product quality or shopping experience. However, problems arise when an “informational imbalance” occurs. In rideshare, this imbalance and lack of transparency prevails, as riders can’t readily justify or comprehend fare differences.

The platforms have their reasons for resisting greater transparency including protecting trade secrets, user privacy, and avoiding costly data management. But our research suggests these concerns, while not trivial, are often overstated. Take privacy, for example. Cities like Chicago and New York have already shown it’s possible to release valuable rideshare data while protecting individual identities. When it comes to trade secrets, sharing information about what goes into algorithmic decisions (like pickup locations or time of day) and what comes out (like driver pay or consumer prices) doesn’t mean giving away the secret sauce of how the algorithm works. Finally, concerns about the high cost of transparency may be exaggerated. The necessary infrastructure and labor are relatively affordable. Based on our conversation with Chicago City officials for hosting their data and associated labor, the annual cost is approximately $65,000, plus an initial setup fee of $35,000. Moreover, if these costs are deemed high for some rideshare platforms, expenses can be distributed through partnerships with transportation agencies, who have proven to be good stewards of such data.

So what can be done? We make three recommendations to policymakers:

- We’re calling for mandatory “rideshare transparency reports,” similar to that in social media and AI foundation models. These would provide periodic and public data disclosures about ride statistics, driver earnings, algorithmic management practices, and platform policies.

- We also need clear standards for how this data is shared. Transparency is not just about data quantity; it’s also about accessibility and usability – monthly releases, public data exports through APIs, and interactive dashboards.

- We need legal protections for the people who engage with this data – drivers, researchers, and journalists. For example, drivers should be able to contest automated decisions that affect their livelihoods without fear of retaliation.

Why should rideshare platforms shoulder these responsibilities? The answer is straightforward. As these platforms increasingly mirror public utilities, they have become a vital part of our transportation infrastructure. This role comes with obligations—obligations that other U.S. businesses already bear in the form of product information disclosures and financial reporting. Public data disclosures are also the foundations for informed research, advocacy for equitable wages, and ultimately, impactful policy interventions. Our research indicates that achieving transparency in rideshare is not just necessary—it’s achievable. Recently enacted transparency regulations in Colorado State – Transportation Network Company Transparency Senate Bill 24-75, represents a promising advancement. It’s now time for policymakers in other regions to act.

The policy memo was prepared by Varun Nagaraj Rao, Samantha Dalal, Dana Calacci and Andrés Monroy-Hernández part of the Workers Algorithm Observatory and in collaboration with the CITP Tech Policy Clinic. We acknowledge feedback on the memo from Mihir Kshirsagar (CITP Tech Policy Clinic Lead), Nina Disalvo (Towards Justice) and Sophie Mariam (Colorado Fiscal Institute).

Speak Your Mind