The FCC recently released the Open Internet Order, which has much to say about “net neutrality” whether (and in what circumstances) an Internet service provider is permitted to prioritize traffic. I’ll leave more detailed thoughts on the order itself to future posts; in this post, I would like to clarify what seems to be a fairly widespread misconception about the sources of Internet congestion, and why “net neutrality” has very little to do with the performance problems between Netflix and consumer ISPs such as Comcast.

Much of the popular media has led consumers to believe that the reason that certain Internet traffic—specifically, Netflix video streams—were experiencing poor performance because Internet service providers are explicitly slowing down Internet traffic. John Oliver accuses Comcast of intentionally slowing down Netflix traffic (an Oatmeal cartoon reiterates this claim). These caricatures are false, and they demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of how Internet connectivity works, what led to the congestion in the first place, and the economics of how the problems were ultimately resolved.

In fact, while there are certainly many valid arguments to support an open Internet, “faster Netflix” turns out to be a relatively unrelated concern. Contrary to what many have been led to believe, there is currently no evidence to suggest that Comcast made an explicit decision to slow down streaming traffic; rather, the slowdown resulted from high volumes of streaming video, which congested Internet links between the video content and the users themselves. Who is “at fault” for creating that congestion, who is responsible for mitigating that congestion, and who should pay to increase capacity are all important (and contentious) questions to which there are no simple answers. To say that “net neutrality” will fix this problem, however, reflects a fundamental misunderstanding. Below, I explain what actually caused the congestion, how the problem was ultimately resolved, and why the prevailing issue has more to do with Internet economics and market power than it does with policies like network neutrality.

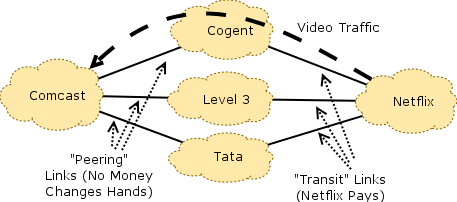

A (simplified) illustration of how Comcast users actually stream Netflix traffic (early 2013). Internet paths between consumers (“eyeballs”) and content typically traverse multiple Internet service providers. For example, prior to March 2014, there were several paths between Comcast and Netflix via multiple “transit providers”, including Cogent, Level 3, Tata, and others. In all of these cases, Netflix paid these transit providers for connectivity to Comcast customers. Comcast, in contrast, had what is called a “settlement-free peering” (or, “peering” for short) relationship with each of these transit providers, where Comcast and each of these providers deemed it mutually beneficial to interconnect.

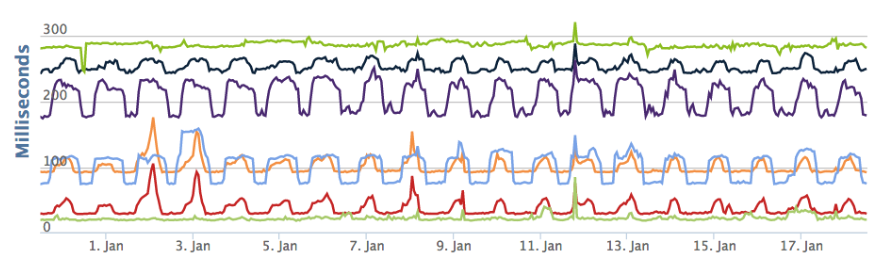

The Internet slows down (mid-2013 through early 2014). Around mid-2013, Comcast users (and other users) began to see congested Internet paths to various Internet destinations, not only to Netflix, but also to other Internet destinations. This phenomenon occurred because the video traffic was congesting paths not only to Netflix, but also paths to other destinations that had some path segments in common with paths to Netflix. In our ongoing BISmark project, we continually collect measurements from hundreds of home networks around the world. In mid-2013, we noticed and documented this congestion; our findings showed that this congestion, visible as extremely high latency, appeared on paths to many Internet destinations. The plot below shows an one consumer Internet connection that we measured in January 2014, which routinely experienced high latency to many Internet destinations every evening during “prime time”—oddly coinciding with peak video streaming hours from home networks. A “normal” latency plot would show flat lines, reflecting latencies that roughly correspond to the speed of light along that end-to-end path (plus small amounts of queueing). In contrast, the plot below shows striking diurnal latency spikes.

When we noticed this phenomenon, we raised it to Comcast’s attention. As it turns out, Comcast already knew about it, and it was clear how to solve the problem: Connect directly to Netflix with high-capacity links. The question was: who should pay for the interconnection? Comcast or Netflix?

The peering dispute: Who should pay? (late 2013 to early 2014) For a period of several months, while Comcast and Netflix were sorting out the answer to this question, Comcast customers experienced routinely high latency during peak hours, undoubtedly caused by congestion induced by video streaming. At this point (and as documented in opposing FCC filings), each side had a story to tell:

- Netflix claims that they were paying for transit to Comcast customers through their transit ISPs, and that they should not be responsible for upgrading the (congested) peering links between Comcast and the transit providers. The FCC declaration went so far as to claim that Comcast was intentionally letting peering links congest (see paragraph 29 of the declaration) to force Netflix to pay for direct connectivity. (Here is precisely where the confusion with net neutrality and paid prioritization comes into play, but this is not about paid prioritization, but rather about who should pay who for connectivity. More on that later.)

- Comcast claims that Netflix was sending traffic at such high volumes as to intentionally congest the links between different transit ISPs and Comcast, essentially taking a page from Norton’s “peering playbook” and forcing Comcast and its peers (i.e., the transit providers, Cogent, Level 3, Tata, and others) to upgrade capacity one-by-one, before sending traffic down a different path, congesting that, and forcing an upgrade. Their position was that Netflix was sending more traffic through these transit providers than the transit providers could handle, and thus that Netflix or their transit providers should pay to connect to Comcast directly. Comcast also implies that certain transit providers such as Cogent are likely the source of congested paths, a claim that has been explored but not yet conclusively proved one way or the other, owing to the difficulty of locating these points of congestion (more on that in a future post).

Resolving the dispute: Paid peering (March 2014). Both sides of this argument are reasonable and plausible—this is a classic “peering dispute”, which is nothing new on the Internet; in the past, these disputes have even partitioned the Internet, keeping some users on the Internet from communicating with others. The main difference in the recent peering dispute is that the stakes are higher. The loser of this argument is essentially who blinks first. The best technical solution (and what ultimately happened) is that Netflix and Comcast should interconnect directly. But, who should pay for that interconnection? Should Netflix pay Comcast, since Netflix depends on reaching its subscribers, many of whom are Comcast customers? Or, should Comcast pay Netflix, since Comcast subscribers would be unhappy with poor Netflix performance? This is where market leverage comes into play: Because most consumers do not have choice in broadband Internet providers, Comcast arguably (and, empirically speaking, as well) has more market leverage: They can afford to ask Netflix to pay for that direct link—a common Internet business relationship called paid peering—because they have more market power. This is exactly what happened, and once Netflix paid Comcast for the direct peering link, congestion was relieved and performance returned to normal. Note: Despite how popular media might present matters, this is not paid prioritization (which would amount to Comcast asking Netflix to pay for higher priority), but rather Internet economics that has borne itself out in peculiar ways because of the market structures.

Whether or not it is “right” that Comcast has such leverage is perhaps a philosophical debate, but it is also worth remembering that the classification of the Internet as an information service (regulation that the government is now backtracking on) is part of what got us into this situation in the first place. And, while it is also worth considering whether the impending merger between Comcast and Time Warner Cable might exacerbate the current situation, I predict that this is unlikely. In general, as one access ISP gains more market share, a content provider such as Netflix depends on connectivity to that ISP even more, potentially extracting increasingly higher prices for interconnection. In the specific case of Comcast and Time Warner, it is difficult to predict exactly how much additional leverage this will create, but as it turns out, these two ISPs are already in markets where they are not competing with one another, so this specific merger is unlikely to dramatically change the current situation.

Various technical and policy solutions could change the landscape, or at least mitigate these problems. Among them, fair queueing at interconnection points to ensure that one type of traffic does not clobber the performance of other traffic flows, might help mitigate some of these problems in the short term. The types of prioritization that the Open Internet Order deals with are, interestingly, one way of coping with congested links. Note that the Open Internet Order does not prohibit all prioritization, only paid prioritization. Thus, we will certainly see ISPs continue to use prioritization to manage congestion—prioritization is, in fact, a necessary tool for managing limited resources such as bandwidth. The real solution, however, likely has little to do with prioritization at all and more likely hinges on increased competition among access ISPs.

“Because most consumers do not have choice in broadband Internet providers, Comcast arguably (and, empirically speaking, as well) has more market leverage”

In other words, if there were more market competition, Comcast would not be in a position to demand payment from Netflix. Comcast is abusing its market dominance to obtain such a payment. In a competitive market, it would be the ISPs paying Netflix for supplying a service that attracts their customers. The bits flow from Netflix to the ISP; because those bits have value, the money should be flowing the other way.

That would mean that the ISPs customers who don’t use Netflix would be subsidizing those that do, which is blatantly unfair.

It is my understanding that most smaller ISPs were in fact forced to do just that, because of Netflix’s excessive market power. If the online TV market were more competitive, they wouldn’t be able to. (Of course, that would require copyright law to be rewritten, which isn’t going to happen in the foreseeable future.)

Nothing “blatantly unfair” about internal company cross-subsidies at all—they happen all the time. Case in point: Microsoft and Intel are losing billions on their mobile efforts, subsidized from their massive profits on every Windows licence and every Intel CPU included with every PC that you buy. Is that “blatantly unfair” if (as is overwhelmingly likely) you are not a user of a Microsoft or Intel mobile product? Yet you probably never even thought about it before now.

That’s not the same thing. Microsoft and Intel presumably expect those efforts to pay off in the long run, and they’re willing to invest money in that hope. They aren’t doing it because some other company was able to force them to do so. More importantly, the price of Windows and the price of Intel CPUs aren’t directly affected, because they’re determined by supply and demand – the money they’re spending on mobile is coming out of their profit margin, not out of my pocket.

If Comcast *wants* to take money out of their profit margin and (in effect) give it away to Netflix, that’s fine by me. But to say that it’s OK for Netflix to use their market power to force ISPs to subsidize them, but not OK for Comcast to use their market power to fight back is unreasonable.

Yes, it is the same thing—“presumably” doesn’t come into it. Whether you call it “forcing them” or “competition” has no relevance to anything.

So explain to me exactly why I should pay more for email because other people like to watch TV over the internet?

I know for certain somethings wrong with the routing. Ive spoken to a few people about this issue and they say the isps blame the peering point and the peering point blames the isp… Sorry im not too technically inclined but i have an inkling that whats being discussed here is directly connected to the latency issues ive experienced the past few months using different isps

Sounds like it could very well be related.

I’m do not know too much about whats been said but i think my issue currently has to do with whats being discussed.

I play a certain video game and ive noticed that my latency has increased for almoat every single server destination in America to the point where the game is simply not playable.

I had time warner and had this issue. Ok so i switched to att… Still have the same issue. I just switched to charter and it has the same latency issue as well. These last 6 months have been really bad. So i thought ok the servers the issue but ive tried various servers throughout the US and they all have the same latency issue. It doesnt matter which ISP i use it seems like all the west coast isps produce the same lag. Ive tried two different pcs and i know its not the game itself because ive played the game on lan and everythings normal.

What I’m experiencing has to do with whats being discussed here… The only question i have is… When will it be fixed?

It is difficult to know for sure *where* the source of the latency problem lies. The plot I included in the original post shows that congestion (presumably caused by streaming video, although we don’t know for certain) can increase latency to all destinations.

One thing to check is whether you’re seeing high latency to your gaming server(s), or to *all* destinations. If it’s the former, then it may be a problem with gaming infrastructure. If it’s the latter (all destinations, or at least more than just your gaming server), then you may be experiencing something that’s related to what I described in the original post. The specific problem that I wrote about largely resolved in March 2014 when Comcast and Netflix arranged a direct peering arrangement (thus moving lots of traffic off of congested interconnects and perhaps even congested transit networks).

However, it’s possible that this problem will return. We’d be happy to send you a device for your home that might help you diagnose the problem, as part of our ongoing research. Feel free to drop me an email if you’d like to dive in further. You may have an interesting case study for us.

I’ve only tried game servers because I know what my latency used to be and what my latency is now. It’s not just me being affected by latency issues. I have been following dslreports.com forums for months now and people from all 3 isps have mentioned that they were having similiar latency issues but the ISP’s maintain that nothing is wrong but we all feel the latency issues. Some of the complaints about latency on dslreports.com dont even pertain to games yet some do but they lodge the same complaints about latency issues. Also, the community (esea.net) i am a part of that pertains to my game also has multiple people from charter, att, verizon and time warner complaining about latency issues. It could possibly just be the game servers but that would not explain why other individuals are not having any latency issues in our community.

Also, this latency issue happened early in 2014 as well but not as bad as it is now. It disappeared from around may/june and reappeared in october of 2014 and hasnt went away.

I will definitely email you. I would appreciate any help in getting to the bottom of this. Thank you.

Also sorry for any grammatical errors im typing from my phone!

Also wanted to share this link

http://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2015/03/netflix-war-is-over-but-money-disputes-still-harm-internet-users/

Dunno if this adds anything to this discussion… You said this problem could return but the article i linked says its still happening? Sorry if i might be confused .. Im trying to piece things together without any real knowledge in regards to how networking works

And ya google helped me find this article too haha

Interesting. The post you reference relates to the very problem I’m writing about, indeed.

The congestion problems certainly have not gone away either in theory (as my original post explains) or in practice (as the article you link points out). Your perception that the performance to game servers improved in early/mid 2014 is also consistent with expectations, and what I described in the original post—after the paid peering arrangement, the existing transit links in Level 3, Cogent, etc. would have seen much less load/congestion. When streaming traffic congests those paths *all* traffic that shares those congested links will suffer

If you are still seeing problems, we’d be very interested to talk to you more and help investigate. I suspect it is related to the problems I discuss in the original post.

“In the specific case of Comcast and Time Warner, it is difficult to predict exactly how much additional leverage this will create, but as it turns out, these two ISPs are already in markets where they are not competing with one another, so this specific merger is unlikely to dramatically change the current situation.”

It is hard to know if that statement was intentionally obtuse or simply disingenuous.

Market leverage derives from the total number customers controlled in the form of residential endpoints. The whole art of the exercise is to exploit that grip which defeats any hope for open market dynamic, which “free market” religion obscures but cannot hide.

If this were not a duopoly becoming a monopoly one might say the customers served, but these customers are captive. Geography is an irrelevant dimension of the economic power relationship. They literally have nowhere else to go in cyber or geo space. The deregulation of the 1990s was complete political economic fraud now bearing its inevitable poisonous fruit to the public interest with lousy expensive service from the most customer hated companies in the country (take that Delta Airlines, amazing someone beat you, but you were part of that same era of economic de-regulation weren’t you) and grossly huge gains solely benefiting a tiny economic elite. Thirty years of Reaganomics will do that to a nation.

The obvious solutions are a) real competition, something that financial Capitalism and the political tools it controls (called Congressmen) will never permit, aided of course by “technical expertise” in pay of advancing the status quo as inviolate, and b) at least an even split of costs.

My expertise is in networking, not economics, so I should not say much more here (and you may be right about market leverage).

I do think that you pose the two options correctly, though: either there needs to be competition, or there should be some sensible regulation concerning how costs are split. Rather than an even split of costs, something derived from (say) the Shapley value might be more appropriate. For example, the contribution from each side should be proportional to the value that they derive from the interconnection. Comcast clearly derives some value from a direct connection to Netflix (some fraction of Comcast subscribers probably view Netflix as *the* reason to subscribe to Comcast, for example). Depending on how much value Comcast actually derives from that relationship (and vice versa), some cost sharing could presumably be regulated. But, I think the devil is in the details as far as exactly how that derived value would actually be computed. Certainly “equal” is not necessarily equitable, in this case (or any peering dispute, for that matter).

I thought this issue would go away if Comcast would deploy OCAs? It’s my understanding that ISPs in competitive markets are delighted to deploy them.

Is the basic economic question whether Comcast can pursue rent-seeking behavior? If the argument is that Comcast needs payment from Netflix in order to finance the upgrade of its network, I don’t think that holds up given where OCAs could be placed. There are open ports, Netflix’s colo is next to Comcast’s, and the cost is a cable. Or is there any demonstration that Netflix traffic is causing internal congestion in Comcast’s network? The analogy there is that you want payment to connect someone’s road to yours because the resulting traffic is more than your road could support. I’d note that the issue is not Comcast or Verizon generally, but only locations/situations where they have a monopoly.

That being said John Oliver’s presentation, while hilarious, definitely has some holes in it. 🙂

I agree. One of the biggest open questions I had when I read the FCC filings is “Why doesn’t Comcast simply deploy Open Connect cache nodes in their network?” Particularly since Netflix offered to foot the bill for deploying those nodes, that was the biggest open question in my mind. I’m not sure what the answer is, to be honest, because I doubt that it’s a question of internal congestion. I have a list of “known unknowns”—including this one—that I’m planning to write up in a follow-up post.

Interestingly, although the Open Internet Order has a clause that prohibits accepting any payment for “managing the network” in a way that benefits particular content (wording that is broad enough to raise questions about preferential pricing on cache deployment!), the order later has wording that suggests that the prohibition does not apply to CDNs. That paragraph is fuzzy, though, because it just talks about CDNs as distinct entities. It doesn’t speak to deploying cache nodes in *someone else’s network*, so one would have to assume that is still allowed (which certainly opens the door for other kinds of anti-competitive/preferential behavior in the future that would technically not be “throttling”).

Good post, Nick, and I love the comment discussion! In your last reply, you offer that you don’t know why Comcast would not accept Netflix’s “offer” to deploy its Open Connect Appliance within the Comcast access network, “[p]articularly since Netflix offered to foot the bill for deploying these nodes.” Like you, I don’t “know” what Comcast’s specific reasons were, but you should be careful saying that Netflix “offered to foot the bill.”

While Netflix does say this, what they are talking about is paying for the cache server that they want to place in the ISP network. This is no different than the “$10 cable” error that you correctly distinguished for one of the other commenters. Space, power, and bandwidth (ingress and egress) are all costs that a third party CDN would absorb. Moreover, these other inputs (for which Netflix does not offer to pay) are not infinitely available within the ISP network. In fact, they are “contested” resources.

Akamai, it its February 9th ex parte letter (asking for the CDN “distinction” you discussed above) explains,

“While ISPs routinely allow content providers and CDNs to place servers caching data in their

facilities, it is not physically feasible to allow all those who wish to do so to place such servers in

any particular facility. In other words, Akamai must often compete with others for access to ISP

facilities. It cannot be otherwise.”

Here http://apps.fcc.gov/ecfs/comment/view?id=60001018795 at p. 5 of 8. So while I don’t *know* Comcast’s specific reasons for not supplying the complementary inputs that Netflix requests it to provide on a complimentary basis, the fact that these resources have positive costs–to which other CDNs (needing the same services) do contribute–makes Comcast’s decision less mysterious (and more mundane).

Also, here’s a link to a funnier peering dispute example where Cogent has a peering dispute with another high-profile ISP. Only in this example, Cogent IS the access network. http://www.colocationco.com/colocationnews/cogentcolocationnews2.htm The article is from the Washington Post, but it’s funny how the Cogent script hasn’t changed much in 13 years.

It’s easy to assume Comcast is the villain in this situation, and that’s the narrative the media adopted. You do a good job of explaining the dispute, and putting it into a more normative context; but, if you want to see some different ways of looking at the possible “whys”–I have a number of posts at my blog: telecomsense.com Finally, here’s a link to one that looks at why Google (and Akamai) asked the FCC to eliminate the Commission’s proposed “interconnection service” (requested by Netflix and its transit vendors). http://bit.ly/1DNSt8m

As to why accepting “free” caches was challenging – that is an easy question to answer! 😉

From an ISP standpoint, putting some 3rd party’s servers in your network can pose a challenge – especially if the 3rd party is big (like 1/3 of the Internet big!) and especially if the ISP is big (meaning every deal is scrutinized for potential to set precedent and/or there are other specific regulatory constraints/concerns). One challenge along these lines is – do you have enough spare space & power in enough places? Demand for space and power could be high and could grow rapidly. Also, once you do it you have to jump in all the way – you need to dedicate people to support it with some reasonable SLA to a 3rd party (installation SLA, monitoring, maintenance, access rights, etc.).

Critically, if you place content in your datacenters for one party then you probably can expect countless others to come ask for exactly the same deal. Before you know it you may as well run a free datacenter for all the Internet’s largest sites and anyone else! Also, you may be hard pressed to just do it for the big guys – otherwise are you squelching innovation for small guys? They want to put racks in your datacenters as well. That sort of feels like you are then in the private datacenter business all of a sudden! So you have to be super careful it is structured in the right way and be 100% confident if you offer it to one large content provider that you can offer it to nearly anyone who asks *and* rapidly so since I could easily see any delay even if legitimate, like a backordered PDU or cooling unit could be spun into ‘foot dragging’ and public complaints on some company blog.

But this approach seems to mostly have been an experiment, or at least a tactic to try to get something for nothing in a manner of speaking. I certainly can appreciate the attempt – it’s like trying to negotiate a lower price on anything – you never know what you can get until you ask. That said, I am sure they knew going in that it would not become their predominant distribution model, which is of course why they started deploying their own servers in datacenters (it is unlikely it came after all those negotiations failed – it seems to have obviously happened in parallel).

– JL (Comcast engineer)

Is the debate over the Netflix event sort of tangential to the core question of whether or not the goal of Net Neutrality remains valid?

It was my impression that what NetNeutrality was about *preventing* carriers from arbitrarily discriminating [in the future]. Will it?

I favored NN because (if I understood it correctly) it meant that Comcast couldn’t decide to throttle its competitors’ traffic; it would be required to treat competitors’ as it would treat its own content, thus removing the temptation to throttle them in order to drive customers to its own services.

But perhaps I misunderstood.

You have hit the nail on the head. The main point I was trying to convey was that the Comcast-Netflix situation is orthogonal to the question of network neutrality, even though popular media has conflated the two issues.

There are many reasons to like “network neutrality” (in short, it is a ban on “paid prioritization” although it’s more complicated, as I’ll explain in future posts). Anti-competitive behaviors such as the one you mention are one reason to favor network neutrality / bans on paid prioritization. That said, banning paid prioritization won’t prevent situations like we saw between Netflix and Comcast from happening in the future because (as you correctly observe), the two issues are different. And, it becomes more complicated when we get into the details of how the Internet actually works, because there are good reasons to prioritize traffic, and there are also other anti-competitive behaviors (e.g., placement of caches) that the FCC order doesn’t actually prevent. There are still lots of open questions.

So, I think you understand things perfectly, when you observe that the two issues are different. To prevent situations like we observed with Netflix and Comcast would actually require some way of injecting competition into the access ISP market. This is something that Wheeler has also talked about, but net neutrality does not have much to do with this issue.

Another reader writes me privately: “Nice thoughtful article about net neutrality. My only quibble is that I do think that Comcast forcing Netflix to pay for upgrades could be subjectively considered paid prioritization.”

This is a great point, and this semantic blurriness is at the root of the confusion reflected in the above comments. Who pays whom is an old topic in the economics of Internet connectivity—typically, the side that “benefits more” pays for the interconnect, or sometimes the cost is shared. In fact, in the 2000s, the “tier-1 ISPs” (Level 3, Cogent, AT&T, etc.) were in the rosy position where everyone paid them to connect, regardless of the direction of traffic. It’s interesting and poetic that the tables of the early 2000s are now turned.

One could reasonably be concerned about Comcast’s ability to extract high prices or force other networks to pay when connecting to it. One could also be concerned about whether Comcast’s market power allows it to extract these high rents to instead encourage people to use Comcast services or consume Comcast/NBC content. But, that relates to competition and market dynamics and is a very different thing than “paid prioritization”, where an ISP would explicitly throttle (or prioritize) traffic and accepting payment for differential treatment.

I believe the FCC’s order explicitly excludes interconnections from scope, for now, on the grounds that they lack expertise in this area.

Exactly right. The order says: “While we have more than a decade’s worth of experience with last-mile practices, we lack a similar depth of background in the Internet traffic exchange context.” In other words, what you said.

Interconnection may likely be the next powder keg. The other thing they mention is this:

“We decline at this time to require disclosure of the source, location, timing, or duration of network congestion, noting that congestion may originate beyond the broadband provider’s network and the limitations of a broadband provider’s knowledge of some of these performance characteristics.”

In other words, the FCC acknowledges that they don’t actually even know where the congestion is really occurring. That’s no fault of the FCC—pinpointing congestion is a very tough problem, and something we and others are actively researching—but the statement also rightfully acknowledges that the congestion may not be in the access network, or even at the interconnection. From our own work, we know that it’s sometimes in the home itself, but there are also (as yet unproved) assertions that the congestion may in fact be elsewhere, too, such as in certain transit providers. I plan to write a follow-up post on exactly this issue.

Unfortunately, until the interconnection issue is tackled, problems are not likely to go away. The cleanest way to tackle that would be to enable viable, robust competition in the access market. Let’s see where that goes…

You sir, have missed the whole reason why Netflix was slow. That “congestion” that was caused happened because some $10 connector cables weren’t where they should be. Even though Netflix agreed to pay for those cables, Comcast was unwilling to hook them up. That **is** slowing things down.

In fact, I do mention exactly that point. Read the paragraph on paid peering. Comcast did create those direct connections, after Netflix agreed to pay for them. So your assertion that Comcast was “unwilling to hook them up” is not correct. I encourage you to read the linked articles, and the FCC filings themselves (also linked).

You might instead ask why Comcast was unwilling to host NetFlix OpenConnect cache nodes inside its network, which is confirmed in the filings. They were unwilling to host those nodes, and that decision certainly could be slowing Netflix down (and of course, they shouldn’t _have_ to host cache nodes inside their network either, although I’d personally be curious to understand why they don’t want to do that, especially since Netflix offered to place these nodes in Comcast’s network at their own expense). But to say that they refused to directly connect is actually not true. The dispute concerned who should pay for that connection. Netflix ended up paying for that connection, but that’s an issue of (lack of) competition and market dynamics, not one of an explicit decision to throttle a certain type of traffic.

Incidentally, the cost of interconnectivity is a lot higher than “$10 connector cables”. We’re not talking about an Ethernet cable in your home network here. These connections involve (often very expensive) high-speed equipment. I can research to get you approximate figures if you want to know more, but we’re not talking about $10, or even $1,000.

Having the figures might be useful in debunking the public narrative that the payment Netflix made to Comcast was nothing but profit.

Norton goes into some detail about these costs in his paper “A Business Case for ISP Peering”: http://drpeering.net/white-papers/A-Business-Case-For-Peering.php

Scroll down to “The Business Case for ISP Peering in 2010”. The costs of peering include (1) the cost of backhauling connectivity (i.e., a circuit) into the interconnect itself; (2) colocation fees; (3) fees charged by the exchange point provider; (4) networking equipment costs. According to Norton (based on 2010 figures) those fees total between $13k-$18k per month, depending on how far you need to go to get to the exchange point. Now, presuming Netfix and Comcast are *already* in the same exchange facility (not necessarily a safe assumption, but let’s be conservative), presumably some of the backhauling and co-location fees could be amortized across other interconnections at the facility, but costs are still probably on the order of $10k per month (that’s per connection; if Comcast and Netflix connect at multiple geographic locations, that cost would presumably go up linearly with the number of locations).

Page 4 of Bill Norton’s “Internet Service Providers and Peering” paper (http://www.cs.rutgers.edu/~badri/552dir/papers/AS/norton-isp-draft00.pdf) also talks about these costs, in general terms: “Peering consumes resources (router interface slots, circuits, staff time, etc.) that could otherwise be applied to revenue generation. Router slots, cards,interconnection costs of circuits or Internet Exchange environments, staff install time are incremental expenditures. Further, operating costs, particularly for peering sessions with ISPs without the necessary on-call engineering talent, can require increased processing power for filters and absorb time better suited to paying customers.”

All of this being said, bandwidth is certainly getting less expensive, and Norton goes into that. But, some of those other fixed costs don’t go down much, and so these interconnections are not “free”—it’s quite a bit more involved than dragging an Ethernet cable across the living room, as many may have been led to believe.

Whether Comcast is profiting at the end of the day is not something we’re likely to be able to find out. Perhaps they are. But, it’s disingenuous to suggest that every dime that Netflix paid is pure profit for Comcast. That connection costs real money.

Just to clarify: The comment about the $10 XC was not really literal. The comment made by LVLT spokes was basically trying to say that it “could” be fixed with something as simple .. not that it was ideally fixed with such. Sure, it was a bit theatrical … but while the public got the message (that the solutions should have been implemented a long time before that period because the equipment and labor were not as complicated as many might believe), I doubt anyone in the industry ever expected a $10 cable to be implemented. That said, I’ll also say, just to clear things up with the “sheep”, that throttling does occur, and while it may not be the case that Comcast deliberately slowed down the Netflix bits …., none of this gets us any closer to the actual issue .. nor solutions. The plain fact is that the slow down on tech advancements in last mile have been mainly due to monopolistic practices; 1. preventing competition from entering the space and 2. basically telling consumers “take it or leave it” and not upgrading (why should they?). Now, it is no longer enough to provide backhaul to enterprise, consumers will only be able to consume the products of a future online world IF the pipes are big enough. Development can only continue IF the incumbents stop maintaining of the status quo for their own selfish purposes (nothing wrong with selfish purposes in the Corp world, as long as it does not interfere with all the other selfish interests). – ff

Yep, good points, and astute observation about where the real issue lies (competition).

Throttling certainly occurs (and has occurred in the past)—take, for example, the throttling of BitTorrent traffic, or the well-known practice of throttling mobile users once they exceed a certain level of data usage. The particular issue between Netflix-Comcast, however, was not one of throttling, and the issues (as you mention) boil down to competition. Simply banning “paid prioritization” alone does not guarantee we won’t continue to see these episodes (which, of course, are as old as the commercial Internet).

It’s worth noting that the actual peering companies pointed out that this narrative is pretty much false. Verizon in particular chose not to pay a trivially small fee to fix the problem, instead trying to extract much more money from Netflix in the process and to push customers towards it’s own services. http://blog.level3.com/open-internet/verizons-accidental-mea-culpa/

That’s a good input to the story and, in fact, the Level 3 blog post is consistent with everything I’ve said above.

Let’s dissect a couple of claims in the post that appear to be contradictory; I’ll explain why the narrative is consistent, and more nuanced than what you suggest.

* Verizon was “deliberately constraining capacity” – Read the paragraph in my post beginning with “Netflix claims…”. This is exactly the point. Yes, the links are congested. The question is who should pay to upgrade those links. Those are links *between* Comcast and their peers (e.g., Cogent, Level 3). It’s worth noting that the post you cite is from the Level 3 blog. Of course, they have an interest in arguing that Comcast (or Verizon) should pay to upgrade those links, but by the same token Comcast (or Verizon) could argue that Level 3 should foot the bill. This is not a question of right or wrong – rather, the market power of each party will determine who eventually blinks first and opens their checkbook.

* “the bit that is congested is the place where the Level 3 and Verizon networks interconnect” – This is consistent with the narrative above. It’s also not provably true, but it’s possible (perhaps even likely) that it’s true. Let’s suppose that it’s true. If the interconnection between Level 3 and Verizon is, in fact, the point of congestion, then the question is not whether Verizon is “intentionally throttling Netflix traffic” (as Oliver wrongly asserts), but instead who should pay (Level 3 or Verizon) to upgrade that interconnection point.

Bill Norton has an excellent book on peering economics that explains how these disputes can eventually resolve, but it’s worth noting that since we’re reading the Level 3 blog here, of course they’re going to write a post that argues that Verizon (or Comcast) should pay. Transit providers like Level 3 have a vested interest in presenting a one-sided version of the story. So while it is absolutely true that Verizon “chose not to pay” a fee to fix the problem, (1) that fee is not “trivially small”, and (2) there is nothing to suggest that Verizon is the one who should pay to upgrade the interconnect, as opposed to that cost either being shared, or footed by Level 3. The outcome there is not a matter or right or wrong — it’s an outcome of the economics. What you might rightfully be more concerned about is that an access ISP who monopolizes the access market (such as Comcast or Verizon) has tremendous market power and could reasonably force Level 3 to pay to upgrade the link, rather than sharing that cost. More competition in the access market would automatically resolve that problem. The Open Internet Order (and banning paid prioritization) actually has very little to do with it.

http://media2.policymic.com/9dc9accb3fbb1b53b283f5be708b576f.png

Really? Comcast didn’t intentionally slow Netflix down?

That’s right. More precisely, we have no evidence to suggest that they did. Let me explain a bit more.

Indeed, that’s the plot that is referenced in the John Oliver talk I referenced (the link in the post takes you to the point of the talk where he references this plot). That plot is correct, or at least it is consistent with what we measured as well.

What is false in Oliver’s presentation (and many of the claims in the popular press) is his claim about what *causes* that slowdown. The cause of the slowdown is congestion, not intentional throttling.

If you read the FCC filings I linked above, you will find that not even Netflix claims that any intentional throttling is taking place. This is an issue of congestion (and who should pay to relieve that congestion), not one of throttling (intentional or otherwise).

Independent of the claims in the filings, a more careful technical inspection of that plot explains why congestion (not throttling) is the culprit. That plot shows slowdowns not just to Comcast, but also to AT&T and Verizon. If it were just Comcast, it would be an odd coincidence that AT&T and Verizon also experienced slowdowns that returned to normal on similar timescales. Such correlated slowdowns are caused by congestion along paths between Netflix and ISPs, via common transit providers such as Cogent. The return to normal in March 2014 was caused by a decision that Netflix and Comcast made, but that was Netflix’s decision to pay Comcast for a direct connection, rather than continuing to use congested paths through the transit providers.

Dave Clark at MIT has also written about these observations of congestion in more detail:

https://ipp.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Congestion-handout-final.pdf

A second question is where that congestion is actually taking place. I’ll follow up on that more in a subsequent post.

While this graph does show trend per unit time (over each point in time, the data points tend to move in the same direction), your post sidesteps the statistically significant numbers in that plot. To wit, Comcast’s numbers are outliers with what is assumed to be network congestion. That means it most definitely was throttling data. And that fact is the significant fact; well over network congestion. Then, if what was significant is the data throttling, legislation to limit Comcast-like companies to be able to do that is likewise significant over the points in your post.

While network congestion is a thing, net neutrality stops the problem that John Oliver and others have identified as the significant issue. Your post sidestepping that hurts its credibility even if it doesn’t affect its veracity.

In addition to the fact that AT&T and Verizon also experienced correlated drops in performance (suggesting congestion at either interconnects or transit), we observed in our own data correlated performance drops from Comcast customers *to many Internet destinations*, not only to Netflix. Such wholesale performance drops across the board are indicative of congestion. That congestion also happens to be correlated with peak-hour traffic.

But, I am curious: How else would you explain why declines in AT&T and Verizon’s performance correlates with what Comcast users experienced? (For what it’s worth, Oliver’s graph does not show TWC and Cablevision, but the data at Measurement Lab shows that TWC and Cablevision *also* saw worse performance over exactly the same time period.) Do you suggest that they are all throttling, and that by some coincidence they all shaped up at the same time? That is implausible, given what we know about the paid peering arrangements.

(And, no, net neutrality does not solve the problem, however you define it. In this particular case, paid peering solved the problem, but the issue—and outcome, where in this case Netflix ended up paying Comcast for the connectivity—had nothing to do with prioritization or intentional throttling, and everything to do with the economics of peering and the market power of the respective parties. Part of the point of the post is to correct exactly that misperception.)

Without numbers on total streaming traffic from Netflix, it is hard to say whether there was a sudden surge in traffic that caused the congestion. It is conceivable – perhaps a huge number of Americans bought SmartTVs or streaming boxes like AppleTV/Roku and raised traffic by 50%, with an ensuing fall in average bandwidth per stream. That does seem unlikely, however.

An intriguing possibility: the Appeals Court decision in Verizon’s lawsuit against the FCC (striking down the FCC’s original, milquetoast net neutrality proposals) came out in January 2014 (oral arguments started in September 2013). It may well be the ISPs’ legal departments anticipated victory (later to turn pyrrhic) and approved a plan to play hardball against Netflix. Collusion wouldn’t even be necessary.

As for your argument that other transit destinations also suffered, if Comcast et al are in a monopoly position where they can afford to ignore customer complaints about poor performance with Netflix, they will certainly be able to ignore other destinations that represent a much smaller proportion of their traffic, who are basically collateral damage in the shake-down operation against Netflix.

Even if I disagree with this article’s premise, I agree with you that network neutrality is unlikely to solve all the problems, only the most egregious abuses. What we need is structural separation of access and Internet transit, just as local and long-distance telephony were separated in 1984. If your transit ISP is throttling Netflix, just change to one who isn’t.

Ultimately, the ISPs customers pay Comcast, Verizon and AT&T to transport the bits they ask for, and pay Netflix for access to the content. It’s not as if Netflix traffic is a surprise that came out of the blue – its has represented a huge proportion of US ISPs’ traffic for sometime now, and is relatively predictable. The ISPs failure to deliver on the service their customers paid for, and attempt to use their market power to pass on the costs to a competitor, is nothing short of racketeering.

Great points.

Your comments make sense and are consistent with my original post. Not sure what “premise” you disagree with. The main point was that the issues of congestion, competition, and interconnection have been wrongly conflated with net neutrality.

One thing that you also rightly point out is that we do not actually know whether the congestion that we and others observed was solely due to a surge in Netflix traffic. That said, there is another possibility that could account for a discontinuity, as well: Netflix began deploying its own CDN, buying transit from providers who are known to systematically under-provision (I won’t name names, but if you follow the industry, you’ll probably know which transit providers I’m talking about). This is a possibility—we don’t know if it’s true or false, but it is worth investigating.

Here you hit the nail on the head: “If your transit ISP is throttling Netflix, just change to one who isn’t.” If this were possible, we wouldn’t be having *any* of these discussions in the first place.

There is no doubt that the access ISPs are “playing hardball”, but that has really more to do with the nature of peering economics, and I suspect not much to do with the court’s rulings last year. These kinds of hardball tactics have been going on for decades. See, for example, the classic Sprint-Cogent peering dispute:

http://www.pcworld.com/article/153123/sprint_cogent_dispute.html

(also referenced in the blog post). These types of disputes and tactics are not new; there’s an even an entire book on them (Norton’s “Peering Playbook”). The main thing that’s new here is people’s attention to the problem because it now involves cable companies that people love to hate, as well as the fact that one of the parties in the dispute has significant market power.

Your other comments about whether consumers are actually getting what they pay for is also a fair perspective, but I’m not going to take it up here, because it’s not in the scope of this particular post, where I argue that the Open Internet Order *alone* is not going to solve these problems.

Fazal said: “Without numbers on total streaming traffic from Netflix, it is hard to say whether there was a sudden surge in traffic that caused the congestion. It is conceivable – perhaps a huge number of Americans bought SmartTVs or streaming boxes like AppleTV/Roku and raised traffic by 50%, with an ensuing fall in average bandwidth per stream. That does seem unlikely, however.”

Keep in mind that in October 2013 Netflix made SuperHD available to all users. That seems to have pushed either their servers/datacenters to capacity or exacerbated the capacity challenges their transit providers already had. So look at October 2013 to November 2013. The slope of the bitrate increase — even for Open Connect partners – seems to falls off a bit, which could suggest a bit of a server capacity issue since those edge caches don’t use transit links to get to the Internet. But for non-partners, which was basically most of the Internet, the debut of SuperHD seems to have precipitated a steep decline between October 2013 and January 2014.

According to SEC filings, between October 2013 and January 2014, Netflix also added ~2.33M new customers – quite strong growth.