My book manuscript, Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age, is now in Open Review. That means that while the book manuscript goes through traditional peer review, I also posted it online for a parallel Open Review. During the Open Review everyone—not just traditional peer reviewers—can read the manuscript and help make it […]

After the Facebook emotional contagion experiment: A proposal for a positive path forward

Now that some of the furor over the Facebook emotional contagion experiment has passed, it is time for us to decide what should happen next. The public backlash has the potential to drive a wedge between the tech industry and the social science research community. This would be a loss for everyone: tech companies, academia, […]

Wikipedia Banner Challenge

As you can tell from the banners appearing all over Wikipedia, their fundraiser is in full swing. Despite Wikipedia’s importance as a global resource, only about one in a thousand Wikipedia readers donate. One way to improve that would be better banners, and that’s why my research group is launching the Wikipedia Banner Challenge, a website to collect and prioritize banner ideas for Wikipedia. You can participate by voting on banners and suggesting new ones. It is quick, easy, and even a little fun.

The Wikipedia Banner Challenge builds on previous innovative efforts by Wikipedia to involve their community in the design of the fundraiser, especially during the 2010 fundraiser. In a continuation of that community-driven spirit, Wikipedia announced on their blog that they will be watching the results from the Wikipedia Banner Challenge closely and will use some of the most promising banners during the fundraiser. In other words, your banner could appear in front of Wikipedia users around the world.

In addition to building on previous efforts by Wikipedia, this project also furthers work by my research group on developing methods that enable communities to collect and prioritize information in a way that is democratic, open, and efficient. So far, our free and open source website, www.allourideas.org, has been used by governments and non-profit organizations around the world. The Wikipedia Banner Challenge provides an interesting test case for our methods, and we are excited to see the results. Wikipedians, if you want better banners for the fundraiser, give us your ideas.

Here are links to more information about:

Governor Genro tops President Obama on Citizen Feedback: "The Governer Asks" vs. "Open for Questions"

Something neat is happening in Porto Alegre, Brazil today. Governor Tarso Genro, of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, is meeting with some of his constituents. Of course, that’s pretty normal; governors meet with constituents all the time. What is neat is how those constituents were selected. They are not the ones with the most money or influence, they are the ones with the best ideas.

These 50 constituents were selected to meet with Governor Genro through a process called Governador Pergunta (The Governor Asks). The process started when citizens suggested 1,300 ideas related to five different aspects of health care (e.g., access to care, family health). Next, the Governor’s office launched a major public outreach campaign to encourage residents to prioritize these ideas through an online voting process. To broaden participation, there were public events and even a “voting van” packed with Internet-connected computers that drove around the state. In just 30 days, Governador Pergunta collected 120,000 votes, and these votes were used to select the top 10 ideas in each of the five categories.

To readers in the US, Governador Pergunta might sound like President Obama’s Open for Questions, and the two did have the same admirable goal: to increase public participation in government. But, there were important differences in their implementation that lead me to conclude that Governor Genro’s Governador Pergunta topped President Obama’s Open for Questions.

The first big difference between the two projects was their voting mechanisms. Here’s what they looked like:

Governador Pergunta

Open for Questions

Open for Questions used single-column, approval voting. Visitors to the site could find the items that they wanted and then vote for them. Governador Pergunta used pairwise comparison, meaning that voters were presented with two options and are asked to choose between them. These mechanism may seem similar, but the Governador Pergunta voting system is better than Open for Questions in important ways. (Disclaimer: Now is probably a good time to mention that I’ve been researching pairwise comparison voting mechanisms for several years, and that Governador Pergunta used open-source software developed by my research group. But, more on that later.)

One reason that the voting mechanism in Governador Pergunta is better is that voters made their decisions independently; they had no information about how others had voted. In Open for Questions, in contrast, voters made their decisions interdependently; items were sorted by popularity and this popularity was shown to voters (see screenshot above). This type of interdependent voting system, unfortunately, can lead to strong and unpredictable fads where some ideas get additional support mainly because they had been supported in the past. As I’ve shown in some earlier web-based experiments, the stronger the interdependence of decision-making, the weaker the relationship between underlying quality and ultimate success. In other words, interdependent voting systems are not good for finding the best ideas.

Further, the pairwise comparison voting mechanism used by Governador Pergunta is more manipulation resistant. Recall that in the approval voting system used in Open for Questions, the voters chose which items to consider. This feature makes it easy for a small group of people to rush to a single idea and push it to the top. This weakness was quickly discovered and exploited by the National Organization for the Reform of Marjuana Laws (NORML). In the midst of a financial crisis and national debate about health reform, many of the highest scoring items in Open for Questions were focused on the legalization of marijuana.

With a pairwise comparison voting mechanism, such as the one used by Governador Pergunta, it would have been much harder (but not impossible) for NORML, or any other group, to skew the results because a voter would have had to cast many, many votes before she would get a chance to vote for the idea she wanted to push to the top. Whatever you think about the fairness of marijuana laws in the US, having a system of public participation that is open to manipulation by a small group is clearly not ideal.

Finally, in addition to using a superior voting system, Governador Pergunta topped Open for Questions in another way: it was open-source. Just as black-box electronic voting machines threaten public confidence in elections, so to do black-box systems for other forms of public participation in democratic governance. Any effort to make government more open and transparent using processes that are not open and not transparent seems destined to fail. The source code for Governador Pergunta and the source code for the Pairwise API, developed by my research group and used by used Governador Pergunta, are both open-source. The Governor’s team and I hope that other public officials will build on our work to develop even better ways of making government more open, transparent, and effective.

Finding the best ideas in the world

Policy-makers often strive to solicit ideas from the public, but making this process effective is very, very hard. Americans need only think back to the health-reform town hall meetings last summer, many of which devolved into chaos. Online approaches, such as President Obama’s virtual town hall meeting, have also ran into problems. So, how can policy-makers discover the best ideas from the public?

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)–an intergovernmental think tank–recently faced this challenge. They were planning a global summit for education leaders that is taking place in Paris today (November 4th), and they wanted to bring fresh thinking from the public to this group. To achieve this goal, the OECD created an “idea marketplace” at www.allourideas.org, a website that I have been developing with a team of students and web-developers. An idea marketplace allows groups to collect and prioritize ideas in a way that is democratic, transparent, and open. It’s certainly a lot easier than inviting everyone to Paris for the meeting.

Here’s how it worked for the OECD, more specifically Joanne Caddy, Julie Harris, and Cassandra Davis. They “seeded” the website with about 50 ideas (e.g., “Give teachers regular sabbaticals so that they can be trained outside of regular school time or during holidays.”). Then visitors to their idea marketplace were presented with the question “Which is the more important action we need to take in education today?” and two ideas from the pool. The visitors voted for one of the ideas, and then another pair of ideas was presented. This process of pairwise voting continued for as the long as the visitor wished. Also, at any time the visitor could upload an idea which would then go into the pool of ideas to be voted on by others. In this way the idea marketplace allowed the OECD to collect ideas from the community and have the community prioritize them. Both of these steps–collection and prioritization–are needed for a successful “crowdsourcing” of ideas. Here is what the voting looked like to the visitor:

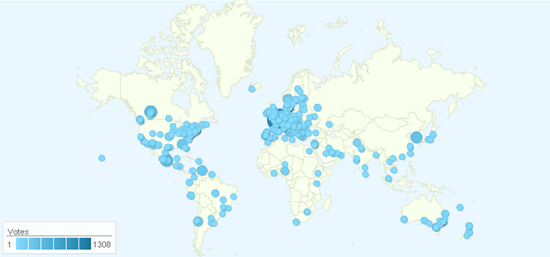

So, how did it work in practice? In just one month, people from more than 90 countries collectively cast more than 27,000 votes.

Equally impressive, these participants uploaded 325 new ideas, again from all over the world.

By combining the voting process with the open uploading of new ideas, this community of stakeholders was able to generate a ranked list that more truly reflected the opinions of the group. The top five ideas (shown below) will be presented to the education leaders today at the summit in Paris, and critically four of these five ideas were uploaded by visitors. In other words, these were ideas that the OECD did not include on their initial list. This example nicely shows how idea marketplaces enable new ideas to bubble-up, allowing groups to learn about things they didn’t even know to ask about.

The top five ideas were:

- Teach to think, not to regurgitate.

- Commit to education as a public good and a public responsibility.

- Focus more on creating a long-term love of learning and the ability to think critically than teaching to standardised tests.

- Ensure all children have the opportunity to discover their natural abilities and develop them.

- Ensure that children from disadvantaged background and migrant families have the same opportunity to quality education as others.

In addition to the OECD, more than 600 idea marketplaces have been created for free at allourideas.org. These have collected about 250,000 votes and 5,000 uploaded ideas. Other policy-related uses have come from student governments (for example, at Princeton and Columbia) and the New York City Government, which is currently using allourideas.org for two projects:

- The Department of Parks and Recreation is using allourideas.org to prioritize residents’ ideas for the new master plan for the parks in Northern Manhattan.

- The New York City Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability is using allourideas.org to integrate residents’ ideas into PlaNYC 2030, New York’s citywide sustainability initiative.

allourideas.org is an open-source research project that has received generous funding from CITP and Google. You can keep up on the project by reading our blog or following us on Twitter or Facebook.