How can we manage the politics and ethics of large-scale online behavioral research? When this question came up in April during a forum on Defending Democracy at Princeton, Ed Felten mentioned on stage that I was teaching a Princeton undergrad class on this very topic. No pressure!

Ed was right about the need: people with undergrad computer science degrees routinely conduct large-scale behavioral experiments affecting millions or billions of people. Since large-scale human subjects research is now common, universities need to equip students to make sense of and think critically about that kind of power.

This semester, with the support and encouragement of colleagues in Sociology, Psychology, and the Center for IT Policy, I taught a sociology class on the craft, ethics, and politics of field experiments, SOC 412: Designing Field Experiments at Scale (open access resources). Building on lessons from this pilot seminar, we plan to assess the possibility of a much larger lecture class. In this post, I review how the class was structured and what we achieved. In a second post, I’ll share what I learned by teaching it, and offer suggestions for future classes at seminar or lecture sizes.

I wove three parallel threads into SOC412: research methods, discussions of ethical/political issues, and participatory research with communities. The syllabus prioritized methods in the early parts of the class, focused on research projects toward the end, and maintained a steady tempo of ethical/political discussions throughout.

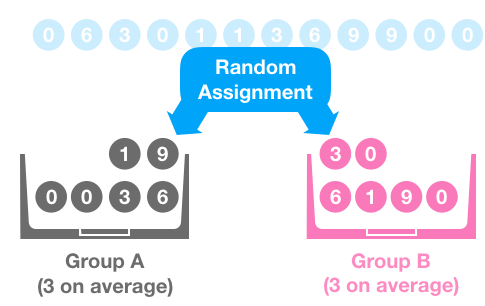

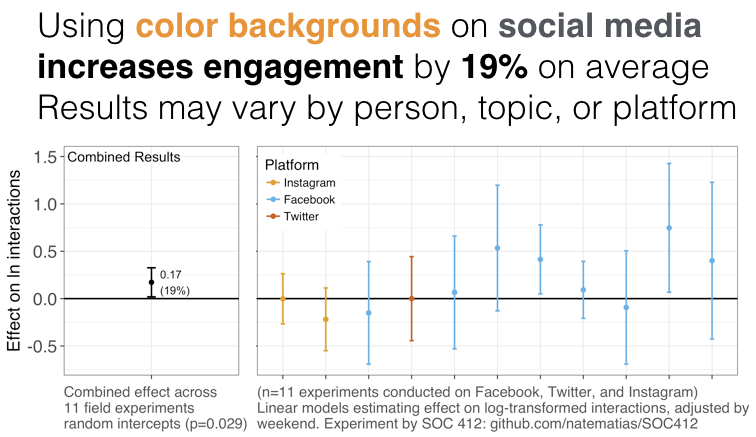

I developed a series of slide decks to help students grow intuitions about experiments. Slides are at github.com/natematias/SOC412

Participatory Field Experiments in the Classroom

Classes on social experiments don’t typically include field experiments, and for good reason. Based on a review of syllabi collected by Martin Saveski, I found that most classes on experiments and causal inference, even at the graduate level, focus on research design and analysis, inviting students to read, recalculate, and comment on published research. Brendan Nyhan’s lab-style seminar on Experiments in Politics is an exception: by the end of the semester, the whole class designs and conducts a single publishable experiment.

Brendan keeps his class manageable by focusing on Mechanical Turk and survey experiments. In these studies, the design is determined entirely by the researchers, and experiments don’t involve observations over periods of time. In my class, neither of those things were true. I wanted students to talk to their research participants and co-design research with them. This would expose students to a greater range of ethical questions. It also made the class more challenging to organize.

Field Experiments: By doing research in a naturalistic setting, students had to think about the tensions between experiments with practical value and scientific questions. Students also were confronted with the ethics of experiments that shape people’s daily lives, in context. Our aim of completing field experiments by the end of the semester also had some risks: (a) Until the study design was finalized, we couldn’t know if experiments would not be complete by the end of the semester, (b) unreliability in any behavioral/administrative measures could lead to surprises part-way through the semester.

In the first month of SOC 412, students conducted a field experiment in their own social media feeds, randomly assigning posts to have colored and plain backgrounds and counting how their friends engaged. Read the results here.

Participatory research: by supporting students to design research with community partners, I was able to ensure that the voices and interests of research participants would be a very real, present part of students’ projects and learning. Students had to negotiate with communities to develop their studies. As I witnessed with Sasha Costanza Chock’s Co-design studio class at MIT, participatory research classes have many risks, and educators can expect that some percentage of class projects achieve something smaller than originally intended.

Delivering meaningful learning experiences with participatory field experiments: To help students learn while also supporting communities in a single semester, I included a lot of up-front scaffolding for student experiments:

- I notified Princeton’s ethics board (IRB) about the class in advance and filed a rough draft of anticipated experiment plans for IRB approval, with the expectation of amending the ethics protocol partway through the semester. Princeton’s IRB was amazing and reliably met our needs.

- Before the class, I organized a community research summit at MIT, whose goal was partly to select potential research partners for the class. Out of 25 study ideas, I narrowed the list of class-appropriate studies to 5 (I’m exploring those other ideas independently)

- In the main, class experiments were conducted using the CivilServant infrastructure with communities on reddit, constraints that narrowed the possible experiments to something achievable in a semester.

- I planned to hire a research manager at CivilServant or work with a TA to support our relationships with partner communities (participatory design classes typically include this role). CivilServant’s research manager, didn’t start until April, too late to support the class, so I did this work in addition to teaching. I definitely plan to include this role next year!

- A software engineer from CivilServant to support student research projects anywhere new software development was necessary.

What Students Learned and Achieved

I had two overarching goals for students of SOC412:that they would (a) develop experimentation skills and (b) learn to think/write critically about large-scale behavioral research. The two-part final assignment included (1) a team project to develop an experiment, accompanied by (2) an individual essay on one ethical or political issue from the class, connected to their team’s specific experiment.

Over twelve weeks, five student teams developed the following studies, all of which are currently underway or about to launch:

- Improving people’s resilience against organized attempts to demoralize people and push them away from an online community.

- Preventing unruly behavior in online communities through automated nudges that monitor the algorithms behind large-scale unruly behavior on reddit.

- Helping people ask better questions in large online discussions

- Testing commonly held theories about phone addiction.

- Auditing tech platforms for [redacted]

Reviewing final student papers, I was encouraged by the depth of students’ connections between experimentation and political/ethical issues. Just to mention a few of the final essays, students wrote on the epistemology and policy of replications, the role of measurement in generalizable knowledge, the ethics of risky experiments involving trauma, methods for crowdsourcing experiment ideas from a wider public, difficulties of estimating risk/benefits in conflict situations, and the legal risks of auditing social platforms.

I also learned a lot from this class. Teaching field experiments gave me ongoing opportunities to revisit my assumptions, articulate ideas clearly in code, and think more about the kind of statistical and ethical learning necessary for public involvement in citizen behavioral science.

I’m proud of what the students achieved. At the same time, teaching and coordinating the class was also overwhelming. In a follow-up post, I say more about what I learned and how I’m thinking about teaching the class next year.