Something neat is happening in Porto Alegre, Brazil today. Governor Tarso Genro, of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, is meeting with some of his constituents. Of course, that’s pretty normal; governors meet with constituents all the time. What is neat is how those constituents were selected. They are not the ones with the most money or influence, they are the ones with the best ideas.

These 50 constituents were selected to meet with Governor Genro through a process called Governador Pergunta (The Governor Asks). The process started when citizens suggested 1,300 ideas related to five different aspects of health care (e.g., access to care, family health). Next, the Governor’s office launched a major public outreach campaign to encourage residents to prioritize these ideas through an online voting process. To broaden participation, there were public events and even a “voting van” packed with Internet-connected computers that drove around the state. In just 30 days, Governador Pergunta collected 120,000 votes, and these votes were used to select the top 10 ideas in each of the five categories.

To readers in the US, Governador Pergunta might sound like President Obama’s Open for Questions, and the two did have the same admirable goal: to increase public participation in government. But, there were important differences in their implementation that lead me to conclude that Governor Genro’s Governador Pergunta topped President Obama’s Open for Questions.

The first big difference between the two projects was their voting mechanisms. Here’s what they looked like:

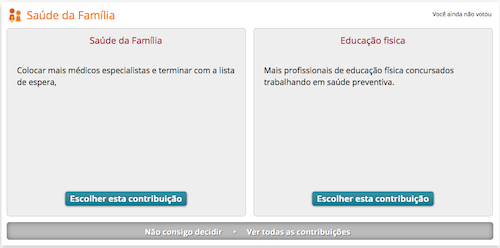

Governador Pergunta

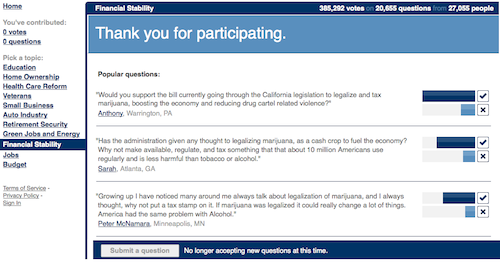

Open for Questions

Open for Questions used single-column, approval voting. Visitors to the site could find the items that they wanted and then vote for them. Governador Pergunta used pairwise comparison, meaning that voters were presented with two options and are asked to choose between them. These mechanism may seem similar, but the Governador Pergunta voting system is better than Open for Questions in important ways. (Disclaimer: Now is probably a good time to mention that I’ve been researching pairwise comparison voting mechanisms for several years, and that Governador Pergunta used open-source software developed by my research group. But, more on that later.)

One reason that the voting mechanism in Governador Pergunta is better is that voters made their decisions independently; they had no information about how others had voted. In Open for Questions, in contrast, voters made their decisions interdependently; items were sorted by popularity and this popularity was shown to voters (see screenshot above). This type of interdependent voting system, unfortunately, can lead to strong and unpredictable fads where some ideas get additional support mainly because they had been supported in the past. As I’ve shown in some earlier web-based experiments, the stronger the interdependence of decision-making, the weaker the relationship between underlying quality and ultimate success. In other words, interdependent voting systems are not good for finding the best ideas.

Further, the pairwise comparison voting mechanism used by Governador Pergunta is more manipulation resistant. Recall that in the approval voting system used in Open for Questions, the voters chose which items to consider. This feature makes it easy for a small group of people to rush to a single idea and push it to the top. This weakness was quickly discovered and exploited by the National Organization for the Reform of Marjuana Laws (NORML). In the midst of a financial crisis and national debate about health reform, many of the highest scoring items in Open for Questions were focused on the legalization of marijuana.

With a pairwise comparison voting mechanism, such as the one used by Governador Pergunta, it would have been much harder (but not impossible) for NORML, or any other group, to skew the results because a voter would have had to cast many, many votes before she would get a chance to vote for the idea she wanted to push to the top. Whatever you think about the fairness of marijuana laws in the US, having a system of public participation that is open to manipulation by a small group is clearly not ideal.

Finally, in addition to using a superior voting system, Governador Pergunta topped Open for Questions in another way: it was open-source. Just as black-box electronic voting machines threaten public confidence in elections, so to do black-box systems for other forms of public participation in democratic governance. Any effort to make government more open and transparent using processes that are not open and not transparent seems destined to fail. The source code for Governador Pergunta and the source code for the Pairwise API, developed by my research group and used by used Governador Pergunta, are both open-source. The Governor’s team and I hope that other public officials will build on our work to develop even better ways of making government more open, transparent, and effective.

It’s a very good point, Matthew. Pairwise comparison votes give a much better way to track the relative importance of an idea.

I’ve seen the same phenomenon with the issue trackers that software developers use. They all support some sort of “priority” or “severity” field, and that field acts much like a singleton vote. The problem is that it’s generally difficult to set a priority in a vacuum. To deal with this, the developers periodically spend an hour or two on triage, where they look at all the outstanding issues and update their priorities in bulk. Because all the open issues are right next to each other, it is a tractable problem to set all of their priorities.

You raise a good point. Namely, public input lacks power when pundits can just claim the result was manipulated..

Your comments remind me of this article:

http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2009/04/13/obamas-effort-online-transparency-stymied-internet-trolls/

So bring on the pairwise voting, if it’ll shut up the people who can’t see a relation between healthcare reform and drug policy.

I will agree with you on you last point, that any such voting system should be open source. It should also be open process, open inputs, and open outputs — under no circumstances should a government be limiting the ways in which citizens provide their opinions.

I disagree with some of the rest, as it appears that you are discarding ethics in favor of tactics.

Tactically, a voting system may be better when voters “had no information about how others had voted”. However, this also means that it is useless to hold the voting in the first place, as the government is perfectly capable of providing whatever responses it wants and claiming that’s what came from the voters. A voting system that cannot be audited by the voters is worse than no voting system at all. And since deadline-based voting systems are infrequently required — meaning continuous debate is not only possible but desirable — you can’t just say that the results will be audited after the voting is complete.

Tactically, a voting system may be better when “a voter would have had to cast many, many votes before she would get a chance to vote for the idea she wanted to push to the top”. However, this is prior restraint on free speech — government should not be preventing people from expressing opinions. The NORML case is simply an example of first-mover advantage in a nascent system. Saying that we should use an ethically-flawed voting system to prevent the NORML case is like saying we should have shut down the Web back in 1995 due to the use of the blink tag.

I agree that fads and rushes are problems. The solution is not to toss out ethics, saying that the government should run a voting system where the government dictates the questions and the answers. Mostly, the solution is time and education, with a healthy dollop of culture, all designed to empower a voting system that is of the people, *BY* the people, and for the people.

Mark, I don’t see, in which way hiding information on how others voted would be discarding ethics. My remarks take it as granted, that the end result of the poll was made public, that nobody was forced to take part and that this is not the only way to make your voice heard of in this country.

First: How should your plea fit voting in secret? Or votes immediately tabulated: Would you prefer an election day with permanent updates in the news on who was in front, quite like in a horse race? I don’t.

Second, tactics are subject to ethics just the same. Put it this way: Is it ethically sound for the government to confront the public with lots of questions, they do not have an interest in, before they get to see the questions, they have their answers ready? How does this fit the notion of a republic, a pool of common issues? I can see it as a way to reinforce that.

I worked with Matthew on the earlier iterations of the pairwise voting software. The first problem you mention, that “the government is perfectly capable of providing whatever responses it wants and claiming that’s what came from the voters” is a problem generic to every voting system, including the voting system used by the White House, and it is not any more prevalent in a pairwise voting system.

The implication that pairwise systems “cannot be audited by the voters” is false. Pairwise systems can be easily audited by voters, votes can be made public as they are cast, in fact we did this in an earlier pairwise system, called Photocracy. All this can be done while maintaining the integrity of the voting process, i.e. making it difficult to manipulate.

The implication in the final paragraph, that in a pairwise system the organizer can dictate the questions and answers is also false. The problems in a pairwise system are no different from those in a normal list based system. Users can upload ideas in a pairwise system, and these will be put into rotation for voting. In some pairwise experiments I’ve seen that uploaded ideas have come to dominate the initial organizer provided ideas.

The question of pairwise voting placing “prior restraint on free speech” is interesting and shows the limits of pairwise voting, I think your point deserves to be explored more.

Hello,

I work on the Digital Office, the team who conceived Governador Pergunta and several related projects. We have discussed many subtle issues regarding this process as we proceed with adopting pairwise voting.

Now, I can agree there is a “prior restraint on free speech” to some extent, but I don’t think such restraint is different from restraints of a traditional election: generally, they are designed to allow a unique kind of expression: a single preference among all options available — and no other kind (ie. there is no way I can express “this is a bad option” or, perhaps, inform an ordered set of preferences).

As I see it, pairwise voting and traditional voting make different questions: my free speech is confined to answering the question as they came, in the proper format (“my choice among all options is this” or “between both options presented, I prefer that”).

Also, I think there is the question of whether one is performing an election or a survey. Specially, if one is advertising an election or a survey to the public, which probably changes their expectations.

Cheers